Forged from a hobby farm in Picton NSW, the Twynam agribusiness empire grew to become one of the biggest landholders in Australia. The group is still held by its founders, the billionaire Kahlbetzer family, who own four Dark Companies on the Secret Rich List.

| Top 200 Rich List (2020) | No. of Dark Companies: 4 | Political Donations since FY 1998-99 |

|---|---|---|

| Rank: 92 | Kahlbetzer Investments Pty Ltd | Labor Party: $0 |

| Wealth: $1.1b | Twynam Group Holdings Pty Ltd | Coalition: $60,150 |

| Wealth (2019): $1.7b | Twynam Investments Pty Ltd | Independent: $0 |

| YoY wealth change: -35.3% | Twynam Pastoral Co Pty Ltd | Total: $60,150 |

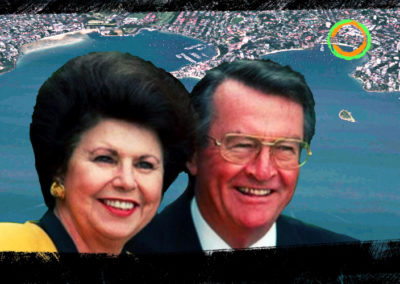

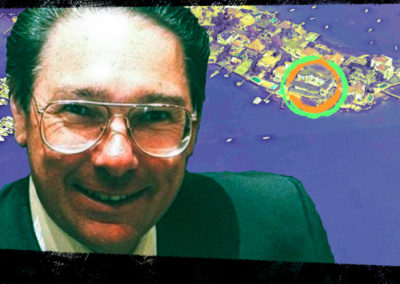

John Kahlbetzer emigrated to Australia from Germany in 1954 and began work in the steel industry. In 1969, he bought a 100ha farm in Picton NSW, which would mark the beginning of the Twynam Agricultural Group.

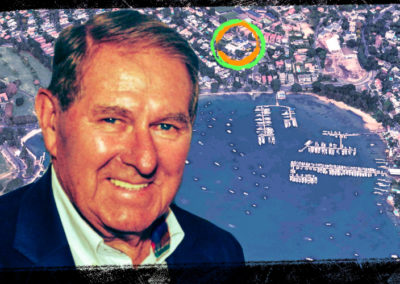

The ensuing decade saw Kahlbetzer purchase additional properties across NSW, most notably seven properties owned by the Naroo Pastoral Company in 1979. His son Johnny Kahlbetzer joined the business in 1991 and remains on the board today. Last year, the patriarch listed his landmark Deepdene building in Elizabeth Bay for $6.5 million.

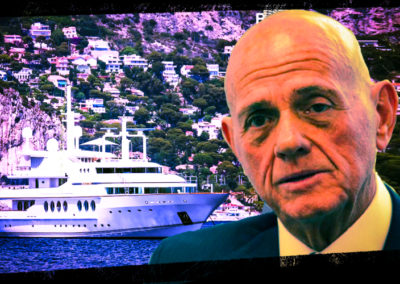

John expanded overseas in 1982 when he created his Argentine agricultural operation LIAG, positioning his group in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with links to the tax haven of Monaco. His second son Markus manages BridgeLane, which houses Twynam’s Argentine agriculture operations as well as property and technology investments within Australia. Kahlbetzer Investments Pty Ltd, a Dark Company, is parent to the empire’s property arm.

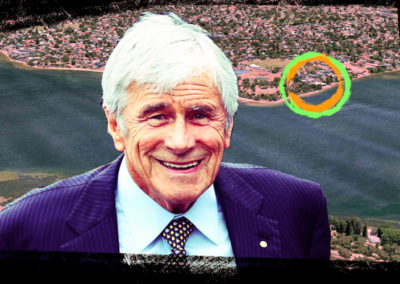

The Group’s most significant acquisition came in 1999 when they bought Australia’s largest cotton producer and distributor at the time, Colly Cotton. The takeover bid was valued at $139 million and lent Twynam the title of Australia’s largest agricultural producer. They have also made significant investments in the mining industry both in Australia and overseas.

Twynam reached peak agribusiness operations in NSW around the early-to-mid 2000s, operating 443,275ha across 19 properties. They were also the largest irrigator in Australia, holding approximately 260,000 megalitres of river water and 38,000 megalitres of bore water (groundwater accessed by drilling).

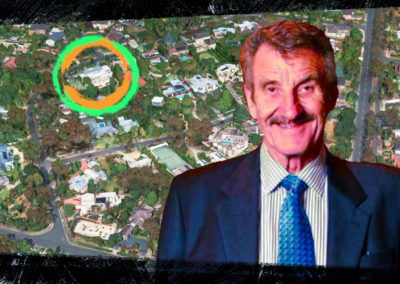

That was until 2009 when the Rudd Government purchased 240 billion litres of water from the Group and their Dark Companies for $300 million as part of the water buy-back scheme. It raised questions regarding the high premiums received by Twynam, as well as concerns about its effect on the market as the sharply raised prices were cut back down after the sale. This rise and fall hurt other irrigation farmers “as it dramatically changed the debt-to-equity ratios of properties overnight”.

It was this sale which Barnaby Joyce then used to justify his infamous water license deal with tax haven-linked company Eastern Australia Agriculture in 2017. Under Joyce’s supervision, the Coalition paid $80 million for the licenses to a company founded by energy minister Angus Taylor. The sale was “nearly double its valuer’s central estimate”.

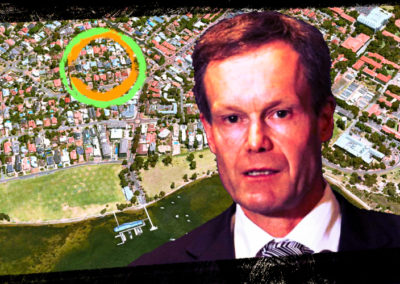

For Twynam, their sale to the Government in 2009 left them with numerous irrigation farms which were now reduced to dryland properties. The Group sold these assets over the coming decade, selling their last large-scale farms, the Lachlan River properties, to foreign investors in 2018 for $115 million.

Largely offsetting their agricultural operations, Twynam now focuses significantly on Venture Capital, investing in green technologies, sustainable farming and renewable projects. Their portfolio includes Opus 12, which are recycling CO2 into chemicals and fuels, animal-free egg products by ClaraFoods, Sierra Energy’s gasifier systems which generate waste into renewable energy and emission-control systems tailored towards power plants by Pacific Green Technologies.

There is no ATO tax transparency data available for Twynam. This adds a further opaqueness to the Group as their Dark Companies cover any potential tax avoidance schemes which would otherwise appear in their financial accounts.

Staff writers who have worked on one or more of our special investigative projects include Zacharias Zsumer (War Powers), Stephanie Tran, Tasha May and Luke Stacey.