On a night out, Manal al-Sharif was made to feel like a criminal by facial recognition. She walked away, wary of the surveillance state, and advises other Australians to do the same, every time.

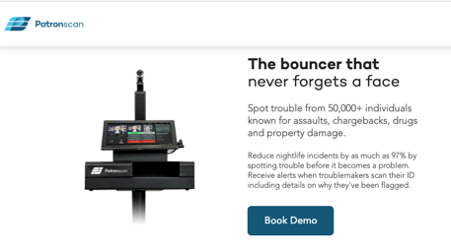

(screenshot from PatronScan. Provided

If Australians knew the extent of the collection and abuse of their online activities and biometric information, they would be marching in the streets demanding decent regulations that protect them against such violations. Unfortunately, when it comes to tech, legislation is either uninformed, out of date, or just embarrassing. That left tech companies on their own to self-regulate, and it’s often in favour of the investors and shareholders. What’s worse, Australians are left in the dark and unprotected when it comes to their digital rights.

I was reminded of the issues on a recent weekend when I went to Sydney’s Ivy Precinct. I was asked to stand before a kiosk camera to verify my ID. The kiosk had the NSW Gov logo attached to it with another tiny logo, barely seen in the dark, it read PatronScan. Suspecting that this was a camera with facial recognition technology, I declined my photo to be taken by this kiosk before I could understand who the hell is PatronScan. The security guard at the door asked me to step back and leave.

I asked if it was possible to verify my NSW ID on my phone or scan the physical one instead of taking a photo of me and registering my ID details with a third party. But the answer was the same: if I refuse to have my photo be taken by the PatronScan camera, I should leave.

I was furious as it was a clear violation of my privacy. There was no consent or any explanation of what I am giving away when allowing that camera to snap a shot of my face.

I took a photo of the dashboard of the kiosk (attached). I wanted to investigate it more. Some of my friends arrived earlier and signed in, not suspecting a major violation of their digital rights. My other friends were standing next to me in confusion. One of them is a lawyer, the other is a financial adviser. Some highly educated people in their field, but not when it comes to their basic human right, privacy.

Photo: author provided

I looked up PatronScan and its parent company Servall Biometrics Inc. This privately held company has four employees and annual revenue of $9.2 million. But their surveillance technology has been used by businesses and law enforcement in Australia for years.

According to PatronScan homepage, the kiosk is used to verify patrons’ IDs. On the same page, PatronScan proudly states that they are helping police and helping businesses, leaving the uninformed customer out of the equation.

As I suspected, their kiosk camera is powered by a biometric scanner made by Servall Biometrics Inc. Biometric information is the electronic copy of our unique bio features such as face, voice, fingerprint, iris, palm, etc.

The camera will capture, catalogue, and identify customers by their biometric information, matching it to their scanned IDs. Whether customers are informed about the facial recognition system is up to the venue owner.

It also collects more personal data such as name, date of birth, gender (as long as you fit their female/male genders list), and area code. PatronScan keeps a “flagged list” of customers with bad behaviour. Those customers are flagged by the venue owner. This “flagged list” comes in handy when the trouble maker tries to go to another venue. If the venue is also using PatronScan, then the system alerts the venue. This list is also shared with law enforcement that goes beyond the city and the country’s borders.

Manal Al-Sharif: Australia’s new surveillance laws remind me of home

According to a PatronScan “Public Safety Report” from May 2018, the average length of bans handed out to customers in Sacramento, California, was 19 years.

Their Privacy Policy page is also problematic. First, they claim they delete your data shortly and permanently:

“Is data given away or sold?

No personal data is provided to third parties outside of law enforcement and venue staff. Again, unless a patron is flagged, data is permanently deleted shortly after visiting an establishment.”

Then they give you ways to ask for your stored data:

“Can patrons request copies of their personal data?

Patrons have the right to request what private information has been collected, used and/or disclosed by navigating to the appropriate privacy page”

When governments defy the people: the authoritarian blueprint for oppression

Establishments have the right to protect their businesses from theft or abuse, but should also take their due diligence in getting the customer’s “express and informed consent” before collecting sensitive data. The what, when and why their personal data is collected, whom they share it with, for how long they retain it, and give ways to customers to have access to the data collected. When it comes to biometric data collected by the venue through a third-party technology, this is my red-line that shouldn’t be crossed.

According to OAIC page on biometric scanning:

“Under the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act) your biometric information is sensitive information. This means that if the Privacy Act covers the organisation or agency collecting it then they must first ask for your consent, with some exceptions, and also make sure it has a high level of privacy protection. The Privacy Act covers Australian Government agencies and any organisation with an annual turnover of more than $3 million, and some other organisations.”

The annual turnover leaves tech start-ups off the hook when it comes to collecting and using our personal data.

Again from the OAIC Consent to the handling of personal information page:

“Consent must be informed

Your consent is only valid if you’re aware of the consequences of giving or not giving your consent at the time you make the decision. An organisation or agency should:

-

clearly explain how they want to handle your personal information

-

communicate their request in plain English, without legal or industry jargon”

Everyone, regardless of how much or how little they value privacy, should have the right to choose how private or not private to be. The lack of consent and transparency surrounding facial recognition technology is an increasingly pressing concern as it becomes more normalised. It’s no longer just our mobile phones and surveillance cameras watching our every move – now we have the venues and shops scanning our faces as we enter them.

My main concern is that most of the time we have no clue where our biometric data will end, who will have access to them, how long they are stored, and how can we have access to them. The worst, we are not given alternatives. It’s either take it or leave it. It’s an asymmetrical relationship where we are left with no rights, no options, and no protection.

My other concern is how these loose practices risk our right to no discrimination. In the case of “Flagged List”, the bad behaviour is left at the discretion of the venue owner. The only way to remove yourself from the doomed list is by contacting the venue itself, and good luck finding which venue flagged you. If that is not resolved, then plea to PatronScan to open an investigation. You have no free choice or self-determination when your name has been added to the list and shared with other venues and law enforcement.

You might think it’s just individual data being collected for everyone’s safety, but looking at the collective harm of collecting all this data on certain demography, no one can guarantee 100% it will always be protected against abuse or theft. We risk the safety of the citizens of a whole city or a whole country when their data is mined recklessly and could end up in the wrong hand. We can change our passwords when they’re stolen, but we can never change our biometric data.

Tech companies are selling mass surveillance to anyone who is willing to pay. The normalisation of this practice has been passively allowed by governments, which refuse regulation and instead rely on tech firms’ self-policing mechanisms–to date these have no deterrent effect because they’re ineffective in preventing abuse (in fact there’ve been numerous cases where violations were ignored).

Ivy is not the only one that is using tech of mass surveillance. Bunnings, Target, the Good Guys, 7-Eleven, Taronga Zoo, the parking lot at the mall, and loads of other businesses in Australia, employ the technique. A very worrying state faced with silence from the regulators.

We are really left in dark about our privacy rights, and left on our own in the fight to protect them. Next time any organisation uses facial recognition technology or asks to take a photo of your face, just walk away. This is a violation of your basic human right, a right that has been abused and neglected the most, the right to privacy.

Manal al-Sharif is a human rights activist, cyber-security expert, author and public speaker. She hosts the Tech4Evil podcast that discusses the intersection of technology and human rights in Australia and the wider world. You can find Tech4Evil.com here. Twitter feed here.

MWM sent the following questions to https://merivale.com that owns and operates the Ivy.

- Do you inform your customers that the camera on PatronScan Kiosk at the door of your Ivy venue is powered by facial recognition technology?

- Do you inform your customers that you are collecting their facial prints using third-party technology?

- Do you get any type of consent from your customers before collecting their sensitive personal data?

- Do you give your customers alternatives for ID verification if they don’t wish their biometric data to be collected?

- Do you share your customers’ facial print data with law enforcement? If yes, under what circumstances?

State of Surveillance: if Pegasus can hack Jeff Bezos’ phone, is there anywhere to hide?

Manal al-Sharif is an author, speaker, human rights activitist and a regular contributor to international media. She has written for the Time, the NY Times and Washington Post. Her Amazon bestseller memoir, Daring to Drive: a Saudi Woman's Awakening, is an intimate story of her life growing up in one of the most masculine societies in the world.

Manal is a cybersecurity expert and host of the tech4evil.com podcast that discusses the intersection of technology and human rights.