The implementation of the new design has been delayed by the Australia and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation, which is chaired by Liberal Senator Richard Colbeck.

The forum sent the label back for review just weeks after Colbeck met twice with alcohol industry lobbyists, including a major political donor.

Libs/Nats donor Lion wins Supplier of the Year at 2019 Australian Drinks Awards. Mark Powell accepting award from Steve Andrews, Advantage General Manager VIC/QLD/SA. (Image via https://www.drinkstrade.com.au/)

Lobbying experience

Senator Richard Colbeck

Colbeck himself boasts first-hand lobbyist experience after operating as chairman for Responsible Wagering Australia before returning to parliament in 2018. His Revolving Doors profile can be found HERE.

In May, Colbeck justified in parliament the delay on implementing the new label. His reasoning mirrored that of arguments put forward by the alcohol industry’s peak body, Alcohol Beverages Australia (ABA).

Colbeck said that a label with red warning text would not be noticeable enough on a red bottle and that the labelling would place “an unreasonable cost burden on industry”. The ABA has opposed the new design on the basis that the “use of red lettering would make the new label more expensive to print”, argues the labelling changes would cost manufacturers $400 million and objects to the use of the term “health warning”.

FSANZ and Centre Alliance senator Stirling Griff have countered this figure, saying that their analysis concluded “the one-off cost to alcohol manufacturers implementing the new labels was $4924 for each product, while the annual cost to taxpayers of health and disability services for new Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) cases was $3 million – $13,847 per person”.

Powerful medical college intervenes

Prof John Wilson

The president of the Royal Australian Colleges of Physicians has now intervened to apply pressure on the ministers to accept the new design at their meeting on July 17.

Two days ago, Professor John Wilson wrote to all the food ministers, urging them to adopt the label “to clearly alert the community to the harm from using alcohol when pregnant” and said the design “must be retained without any changes that might result in watering down this crucial message”.

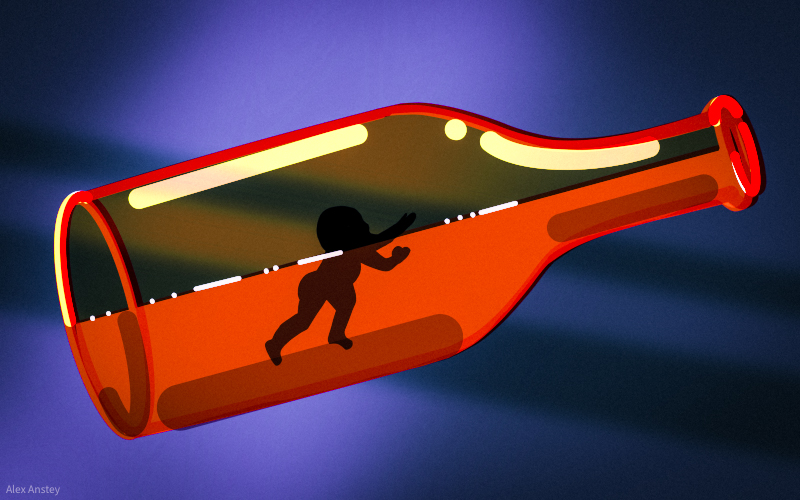

The new design proposed by Food Standards Australia New Zealand is a clear improvement on the current industry standard warning composed by DrinkWise, which is funded almost entirely by voluntary contributions from alcohol industry.

Ineffective messages

As long ago as 2012 health professionals were warning about the effectiveness of warning labels “if they are voluntary and if DrinkWise is responsible for their size, orientation and message”. Moreover, the most common of the voluntary DrinkWise labels used by industry is the innocuous, uninformative “Get the facts” logo.

In the article “Vested Interests in Addiction Research and Policy: Is the alcohol industry delaying government action on health warning labels in Australia?” published in the Society for the Study of Addiction the 63 public health professionals also raised concerns that the DrinkWise pregnancy warning label “could be easily ignored by the consumer: it is a thumbnail-sized text-free image … located in the least visible part of the label.”

And those concerns remain valid. FASD is a preventable disability yet complicates almost 5% of births in Australia annually. And as Professor Wilson wrote: “Almost a quarter of Australians are not aware that drinking alcohol when pregnant is harmful to an unborn baby, resulting in around 75,000 alcohol-exposed pregnancies every year. In a recent NSW pregnancy cohort over 60% of women drank alcohol during pregnancy.’”

Furthermore, “Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder has lifelong health consequences with great economic and social costs, including spending on health, education, welfare and criminal justice, as well as untold losses in human potential.”

Concerns about DrinkWise involvement

The above redesigned pregnancy alcohol warning label (LEFT), released by FSANZ in October 2019, was redrafted partly to address concerns around the “DrinkWise” label (RIGHT), which does not include a written warning and directs consumers to a website funded by the alcohol industry.

DrinkWise is also the organisation responsible for 2400 pregnancy warning posters that contained incorrect and misleading messaging. The posters had to be removed from hospitals and GP clinics nationwide. While the headline on the poster: “It’s safest not to drink while pregnant” reflected government guidelines, the text beneath, including the words “It’s not known if alcohol is safe to drink when you are pregnant”, was considered misleading and inaccurate.

DrinkWise and other industry representatives have even gone so far as to assert that “a pregnancy warning label for alcohol products would create anxiety among pregnant women and result in them choosing to abort their pregnancy”.

ABA chief executive Andrew Wilsmore has argued that putting what he deems excessive information on a label is risky because: “If there’s too much information, you get this thing called label haze, where nothing gets taken in at all.”

While a 2014 article from the International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research noted that “any proposal to introduce alcohol warning labels as a core strategy to address maternal alcohol use should be carefully considered”, it also argued that larger and more colourful warning labels, with either graphics or images (including “graphic” images of harm) gained maximum, sustained attention. The proposed redesign clearly fits this mould.

Effective strategies to delay action

The 2012 article “Vested Interests in Addiction Research and Policy” also outlined four key strategies the alcohol industry employs to resist stronger warning labels, strategies that have been on show recently by Senator Colbeck and powerful lobbyists including Andrew Wilsmore.

They were:

- Arguing against the evidence and rationale for labelling

- Arguing that warning labels may have negative consequences for public health and the economy

- Lobbying and seeking to influence government and political representatives, and

- Delaying effective action on labelling by introducing a voluntary labelling scheme with weak, ambiguous messages.

The alcohol industry has fought long and hard along these lines. For example, various industry bodies put in submissions to the 2011 Inquiry into the prevention, diagnosis and management of FASDs by the House of Representatives Standing Committee of Social and Legal Affairs. Here are some of the arguments put forward.

- The Winemaker’s Federation Australia used the higher prevalence of FASD in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to question the need for population-wide exposure to mandatory warning labels.

- The Distilled Spirits Industry Council of Australia (DSICA) suggested that because 97.5% of women “positively alter” their alcohol intake during pregnancy that awareness about FASD must already be very high in the community.

- DSICA and Brewer’s Association of Australia both suggested that because FASD is an issue concerning female consumers only that warning labels should only be applied to certain female-preferred alcohol products.

————————

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/australia-gambling-lobbyists-luke-stacey/

Luke Stacey was a contributing researcher and editor for the Secret Rich List and Revolving Doors series on Michael West Media. Luke studied journalism at University of Technology, Sydney, has worked in the film industry and studied screenwriting at the New York Film Academy in New York.