Government contractors have to report on their performance every month. When there is a cost blowout or progress is behind schedule, the department responsible for the spending knows about it, but we rarely do. What’s the scam?

From Snowy 2.0 to other energy and infrastructure projects partially funded by the government, it spends tens of billions each year on large projects, and from time to time, the Auditor General does a big reveal on a major Government project that’s gone off the rails. Or, occasionally, a senator asks the right question in Senate Estimates and a taxpayer’s sinkhole is discovered. The Government will have known it for some considerable time, sometimes for many years, but will have just kept the mess a secret.

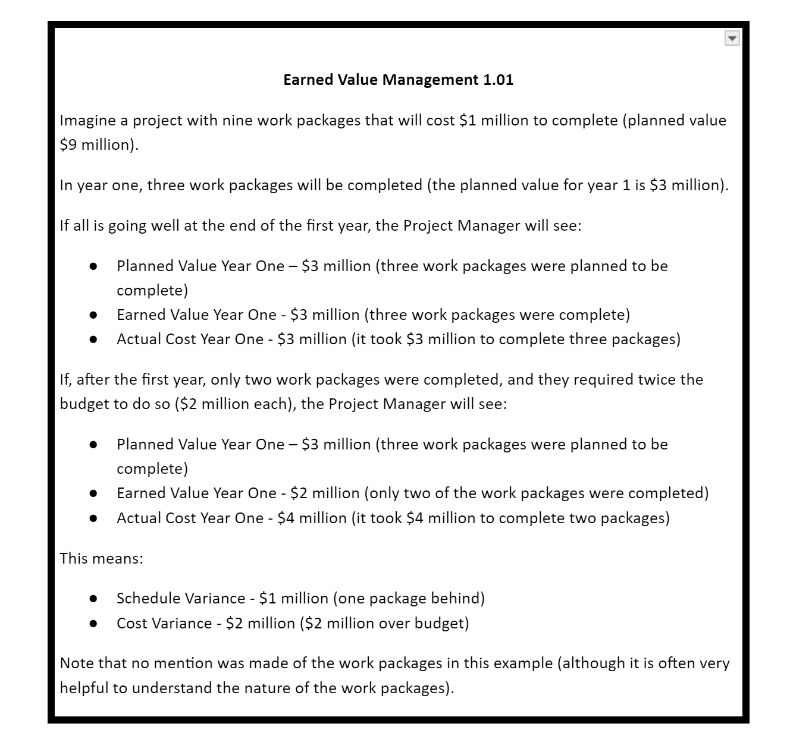

The industry standard for measuring project performance is referred to as ‘Earned Value Management’ (EVM – see below). It has a simple way of signalling a cost or schedule variance. It does so with numbers; it does not reveal anything technical about the project.

Monthly EVM reports in Government projects are paid for by the taxpayer and are a contract deliverable, meaning they belong to the taxpayer. They ultimately report what the taxpayers’ exposure is in terms of cost blowouts and how long the public will be without the project output (that is to say, a ship, a building, a road, a dam, the online software service, etc).

Early public notice of a blowout in cost or schedule would assist parliamentarians, the media and the public in putting pressure on the Government to pay attention and remedy the situation or perhaps walk away early from a project before more money is wasted.

Imagine being able to watch Snowy Hydro go from an early $10M blowout, to an early $20M blowout and decide to change out the management or terminate the project before it became, as it has, a $10B blowout.

What’s the scam?

We have the information. It’s sitting there. We just can’t see it. Or rather, the Government won’t let us see it.

At the start of each project, the Government enters into a confidentiality arrangement with the company that is delivering the project. They declare the EVM reports to be confidential.

When someone like me comes along and asks for the EVM reports under FOI, they are refused because they are confidential under the contract, and their release could cause damage to the company – including, get this,

because reputational damage might occur to the company if it is seen to be managing a project that is over budget and late.

The taxpayer, who ends up pouring their money into a faltering project to cover the blowouts, gets to suffer because they’re not availed of the fact the train has run off the tracks, just so the reputation of the train driver is not sullied. Never mind the passengers.

AAT ruling

In 2018 I suspected that the Attack Class future submarine project was drifting off its intended course. I sought access under FOI to the project’s original schedule and its monthly ‘earned value management reports’. Defence refused access to that information. The Information Commissioner backed their decision.

Because of the importance of the decision on public oversight of all Commonwealth projects, I took it to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, where lawyers (and I) could argue the matter in a fulsome and unabated way. A two-day hearing occurred in July last year. A decision was handed down this week.

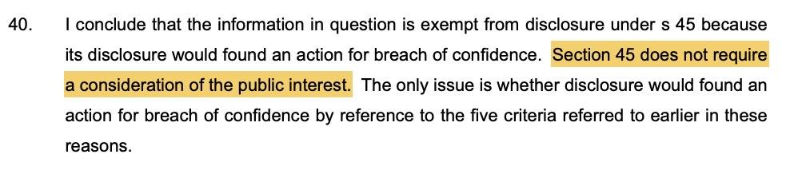

The law says that if an EVM report has been agreed confidential by the Government and a contractor, it can’t be accessed under FOI. The public interest plays no part.

I can’t criticise the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. Deputy President Britten-Jones heard the matter and has, without emotion or bias, declared the law as it is.

Extract from AAT ruling

However, I can criticise Departments for agreeing in the first place to keep this information confidential. But my criticism is likely to fall on deaf ears interested in keeping project failure secret. I can also criticise the Department of Finance and successive governments for allowing this invidious practice in which government agencies and their contractors agree to keep their failures secret.

But I am left now to lobby the Parliament to change the law (I already made a submission to the Senate’s FOI committee late last year, but the Committee’s focus was elsewhere).

A simple change is needed: that the public interest be considered when deciding whether to release the information related to taxpayer-funded projects. It’s not a tall ask. That’s already the law in the United Kingdom.

Regrettably, it will probably take a project failure on a truly monumental scale to force reform. Clearly, the Attack-class submarines and Snowy Hydro 2.0 weren’t big enough debacles. It might take something on the $368B scale of the AUKUS submarine project.

For now, the hole in your back pocket or purse where the money is pouring out of, will remain a secret from you, even if the Government is fully aware of its existence and size.

Rex Patrick is a former Senator for South Australia and, earlier, a submariner in the armed forces. Best known as an anti-corruption and transparency crusader, Rex is also known as the "Transparency Warrior."