As petrochemical giants plan to double new plastics production and the bulk of Australian plastics are tipped into landfill, not recycled, Luke Stacey checks out how other countries are tackling the plastics crisis versus the Coalition Government’s 2025 National Packaging Targets and waste export bans.

The challenges are clear: despite politicians paying homage to recycling, despite ordinary citizens diligently placing their plastics weekly in yellow wheelie bins, the vast bulk of plastics are not recycled, either tipped into landfill or exported, often burned in the toxic process of turning waste into energy for the Third World.

The harsh reality of complex plastics and a costly process to recycle them means the petrochemical giants are actually planning to double their plastics production in coming years. What are we doing about it vis-a-vis other countries in the world?

The Morrison government has moved to address the issue, placing particular emphasis on the necessity for increasing recycling rates in its 2021 National Plastics Plan. However, a CSIRO report in January outlined the key challenges for plastic waste management with which Australia is struggling to contend:

- Lack of plastics recycling infrastructure;

- Contamination of plastics;

- Lack of advanced Materials Recovery Facility sorting technology;

- Lack of reliable, consistent waste data;

- The Australian Packaging Covenant is not mandatory;

- Imported plastics not subject to controls regarding recyclability;

- Lack of market demand for products made of recycled plastics;

- Lack of standards for recycled materials and products;

- Lack of solutions for mixed plastics;

- Lack of life cycle assessment data to inform decisions – resulting in “substitution decisions that may appear more environmentally friendly but are actually more detrimental”.

PET Project: petrochemical giants exploit recycling to ramp up plastics production

An alternative that could help alleviate such challenges is attacking the overconsumption of plastics at its source.

The Minderoo Foundation, established by Australian businessman Andrew Forrest and wife Nicola, released a report in May recommending a levy on the production of virgin plastics and the establishment of a global treaty to “address the problem at its source, with targets for the phasing out of fossil-fuel-based plastics”. The government however is shying away from levies on the petrochemical industry as part of its 2025 waste targets.

San Francisco, US

A case study from the United States Environmental Protection Agency found that the city of San Francisco “implemented the first and largest urban food scraps composting collection program in the US, covering both commercial and residential sectors”.

This has resulted in a collection of over two million tonnes of food waste, household green waste and other compostable materials.

The city has also outwardly promoted the virtues of reducing “virgin” plastics consumption and the reuse of materials in order to achieve its target of zero waste diverted to landfill.

Other initiatives include San Francisco’s Construction and Demolition Ordinance which mandates by law that all construction and demolition debris must be either reused or recycled. Fines and suspension of registration apply for those individuals or companies found to be in breach of the law by sending waste to landfill.

While various parts of Asia have been used as dumping grounds for first-world nations including Australia, the region has implemented several zero waste initiatives despite the added burden of waste from other countries.

And although Australia is now rolling out various waste export bans which will be fully implemented by 2024, it has left a gigantic loophole permitting waste that is turned into toxic energy sources such as Refuse Derived Fuel to continue to be shipped to third world countries.

What’s more, the above CSIRO report found:

“Of the 320,000 tonnes [of plastic] recovered in 2017–18, only 125,000 tonnes were locally processed. This means if exports are discontinued it would be necessary to increase local processing capacity by at least 150% to ensure previously exported plastics do not go to landfill.”

Toxic Waste Rebranded: Australia bans Third World dumping, leaves giant toxic loophole

San Fernando, Philippines

The city of San Fernando in the Philippines has undergone a major transformation in its policy initiatives to work towards a zero-waste future.

One primary initiative is the Plastic Free Ordinance introduced in 2014. The policy “targets business establishments and aims to gradually phase out the use of plastic bags and styrofoam packaging for food products” which is now enforced by law.

The more stringent waste initiatives have also increased employment in the city:

“According to the San Fernando CENRO, there are currently around 160 barangay-hired waste workers working as collectors, drivers, segregators, street sweepers, and MRF managers that earn a monthly average salary of PHP $4,800 (USD $94) with a range of PHP 1,000-10,800 (USD $19.5-211) and an added average potential additional income sourced from sales of recyclables collected from households of PHP 4,700 (USD $92).”

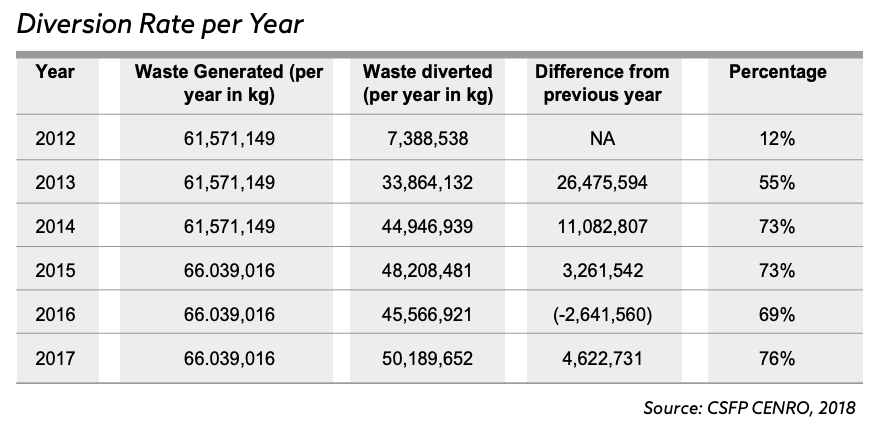

The measures have led to a waste diversion rate for San Fernando of 12% in 2012 to 76% in 2017.

Kamikatsu, Japan

In Japan, the small town of Kamikatsu has implemented an in-depth waste sorting system where residents separate their waste into 45 categories. These include aluminium cans, plastic bottles, newspapers, paper flyers, paper cartons. Barring the elderly population, residents also wash and transport this waste to the collection centre themselves.

According to a case study from the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, this was a practice that “the residents initially found tedious, but which eventually became second nature to them”. Residents also manage all of their organic waste within each household.

These initiatives have resulted in 81% recycled waste for Kamikatsu, which comes in addition to materials that are either reused or composted.

In 1998, the town had installed two waste incinerators as Japan looked to implement waste-to-energy methods as a way to tackle the country’s growing waste problem. Yet, after only three years, “both incinerators were banned following a national regulation due to health concerns about the amount of dioxins produced from small-scale incinerators nationwide”.

Local choke hazards

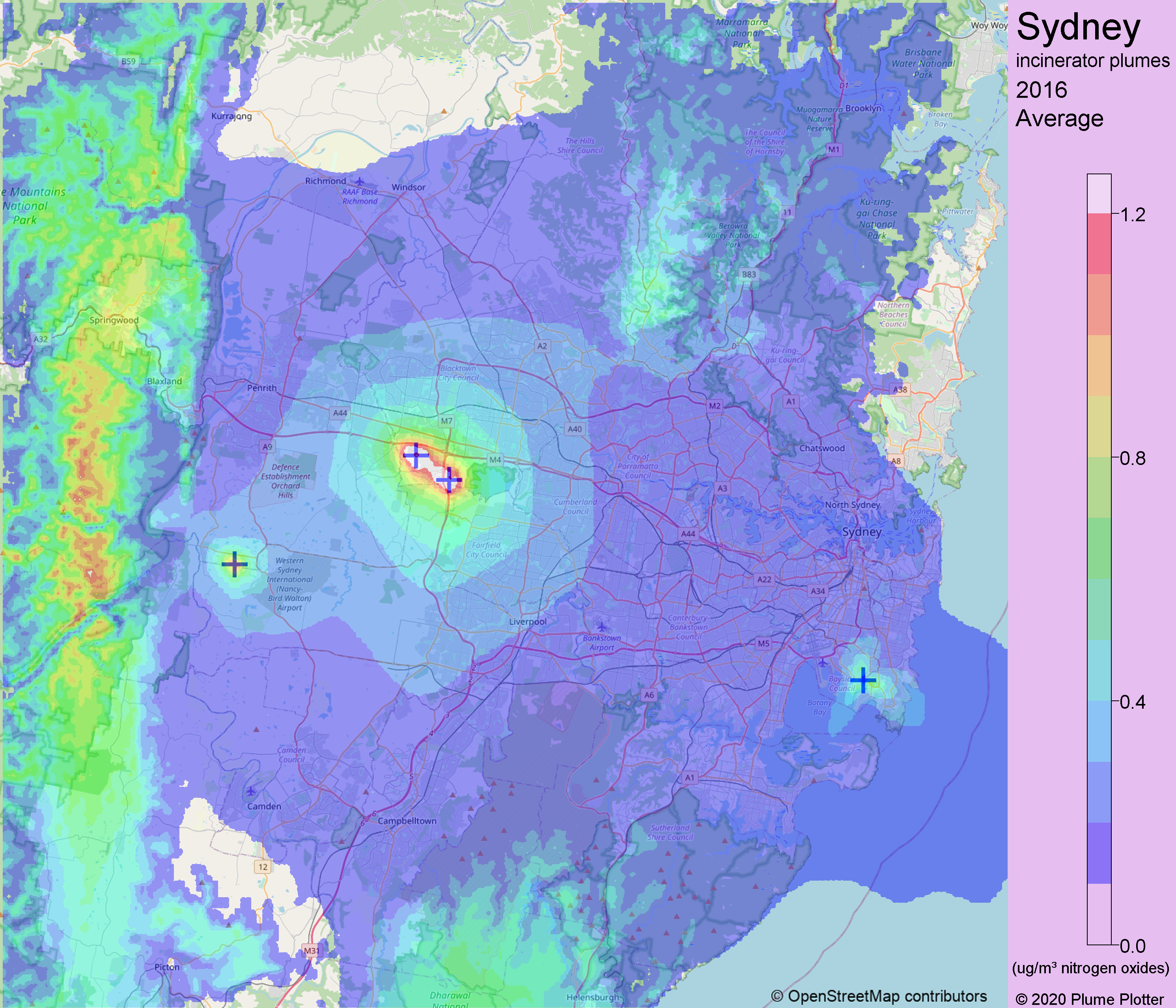

Contrast that to back home in 2021, where multiple waste incineration facilities are being earmarked for high-density urban areas in cities such as Greater Sydney.

For example, multinational waste management company Suez Group is proposing to build a high-temperature waste incinerator to provide steam for Orora’s Botany Paper Mill. This is just one of seven sites proposed for Greater Sydney.

The paper mill is located in the suburb of Matraville, situated in close proximity to Sydney Airport. Yet Matraville is not an industrial suburb, with some residents living just 130m from Orora’s proposed incinerator.

The primary source of fuel for this incinerator will be processed engineered fuel (PEF), with 80% supplied by waste from Suez with the remainder coming from Orora’s paper mill. When burnt, the fuel stream can produce a high amount of dioxins that are considered highly toxic Persistent Organic Pollutants.

Not-for-profit advocacy group No More Incinerators is lobbying the NSW government to oppose the Matraville incinerator and is raising awareness about the wider implications of these polluting facilities.

These dioxins come in addition to other health and environmental impacts of waste incinerators such as the production of toxic ash and dust as well as increased greenhouse gas emissions.

The increased presence of waste incinerators also undermines the recycling industry; an industry that is already struggling to compete with the increased production of virgin plastic from petrochemical giants like Dow and Exxon.

This is because it is cheaper for waste management companies such as Suez to dump large volumes of waste into incinerators than it is to separate and recycle materials to then be sold to a market that prefers inexpensive virgin materials like plastic.

Map illustrating emissions profile for Greater Sydney in 2016 from waste incinerators (Northern Beaches LGA not accounted for).

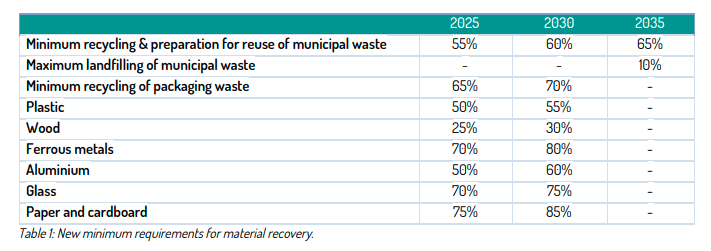

Europe’s waste targets

Returning to a global lens, perhaps Europe is making the biggest inroads in tackling large scale zero waste initiatives by declaring mandatory targets.

A report from Zero Waste Europe outlines the policy enforcements for Member States of the EU such as implementing the following separate collection schemes:

- Paper (already mandatory since 2015);

- Metal (already mandatory since 2015);

- Plastic (already mandatory since 2015);

- Glass (already mandatory since 2015);

- Bio-waste – by 31 December 2023;

- Textiles – by 1 January 2025 Hazardous waste – by 1 January 2025; and

- Waste oils – by 1 January 2025.

The EU has also issued new mandatory targets for recycling and recovery rates:

These plans are part of a wider movement established by the European Commission known as the Global Alliance on Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency. This alliance has been extended to nations outside of the EU, with current members including New Zealand, India, Canada, Colombia, Rwanda, Morocco and South Korea.

Australia is nowhere to be seen.

“Unprecedented action”

In 2018-19, Australia recovered just 11.5% of the 3.5 million tonnes of plastics it consumed that year, notwithstanding other materials such as paper, glass and e-waste.

Despite this, a spokesman for federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley told Michael West Media:

“The Morrison Government is taking unprecedented action to manage plastic packaging waste so we can reduce its impact on the environment.”

This includes targets to achieve 20% average recycled content in new plastic packaging by 2025. But as Director of Zero Waste Australia and the National Toxics Network Jane Bremmer has previously stated:

“Industry is selling plastic recycling to the world as the solution … but they know full well this is greenwashing designed to maintain business as usual as they drip-feed relatively small quantities of recycled plastic into virgin feedstocks.”

Ocean Waste: how plastic recyclers downplay their use of new plastics

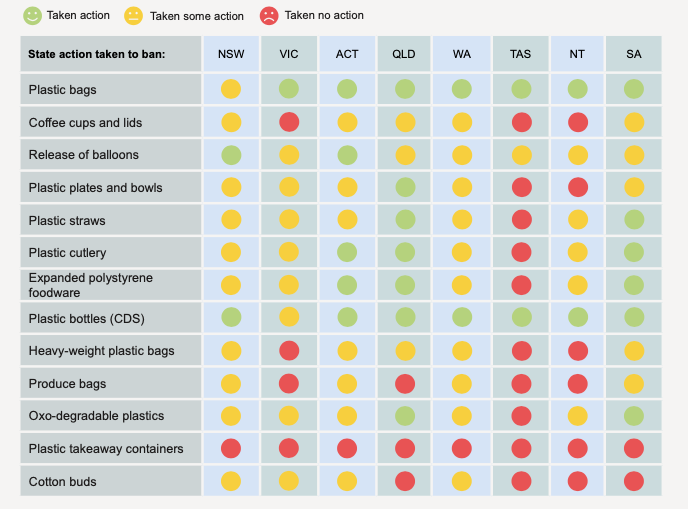

The WWF has released its 2021 scorecard for action taken by the states and territories to implement bans on various single-use plastics. Western Australia took top spot with Queensland running at a close second, while the Northern Territory and Tasmania ranked as the lowest performing regions in the country.

Luke Stacey was a contributing researcher and editor for the Secret Rich List and Revolving Doors series on Michael West Media. Luke studied journalism at University of Technology, Sydney, has worked in the film industry and studied screenwriting at the New York Film Academy in New York.