Debate over Labor’s Safeguard Mechanism has raged like a fire through a Sumatran peat forest. One of the most controversial aspects of the program is the use of carbon offsets, which some of our biggest companies are now buying in Indonesia. Zacharias Szumer reports.

Following credible claims that the Australian carbon offset system is riddled with errors, many are sceptical about the whole concept of offsets. Such scepticism was no doubt bolstered by a recent Four Corner’s episode, which cast doubt on carbon offset projects in Papua New Guinea.

Before we go any further, it’s important to clarify that these are separate systems.

Large Australian companies who need to comply with the Safeguard Mechanism, for example, can only offset emissions by buying Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs). This is known as a compliance market. Any other companies – whether motivated by a sense of responsibility or a desire to burnish their green credentials – can go to what’s called the voluntary market. Here they can offset their emissions via carbon stored in Papuan forests, for example.

But these companies would not be likely to first turn to Papua New Guinea, especially considering the ongoing unrest there. They’d be more likely to try across the border in Indonesia, where a far more established and long-running offsets market is in place.

The offset archipelago

PwC, Delta Airlines, Australian event management company Arinex and Japanese oil and gas company INPEX, have all bought credits from a project named Rimba Raya Biodiversity Reserve Project, in Borneo. Agriculture and chemicals giant Bayer, French investment manager AXA, and cosmetics brand L’Oréal have purchased credits from another, the Sumatra Merang Peatland Project, on the island of Sumatra.

The largest is the Katingan Peatland Restoration and Conservation Project, which has sold credits to Woodside, Volkswagen, Xero, Seek.com, Chevron, BNP Paribas, Shell, Medibank, Zilch, Dexus Industria REIT (an ASX- listed real estate investment trust) and Jan de Rijk Logistics (a leading European transport firm).

Data sourced from Verra.org

Like other offset projects of its kind, Katingan’s promise is simple: that this swathe of peatland forest in southern Borneo would have been cleared – whether logged, drained or burned – and the carbon stored in the peat and trees would be released. The money received through the offsets market stops this from happening.

In terms of estimated annual emissions reductions, Katingan is Indonesia’s largest carbon offset project. In fact, it’s the ninth largest “Agriculture Forestry and Other Land Use” project in the world – at least, of projects registered with Verra, the US nonprofit that runs the world’s leading carbon offset accreditation scheme, covering the majority of all voluntary offset projects.

However, according to recently accessed data, every project above Katingan on Verra’s “Agriculture Forestry and Other Land Use” list was either rejected, undergoing validations, under development or approved but not registered. This means that Katingan is potentially the world’s largest project of this type currently generating credits for the voluntary offsets market.

According to a 2022 report by Dutch NGO Milieudefensie, Shell has bought more credits from Katingan than any other project in the world, bar one. At the time of the report’s publication, Shell had bought 2,955,167 credits from Katingan. One credit equals one tonne of C02 emissions abatement, and 2,955,167 tons is roughly the amount a small coal-fired power station emits in a year.

Controversy and pushback

Katingan received early funding from the Clinton Foundation and was championed by actor Harrison Ford in a 2014 documentary series. It has won sustainability awards and has an A rating with the offset ratings agency BeZero.

However, not everyone is shouting its praises.

A 2020 report from Greenpeace claimed that the project’s “purported emissions savings are based on a chain of questionable assumptions.” It also implies that the founder of the company managing the project, Rimba Makmur Utama, isn’t primarily motivated by environmental concerns.

The report quotes founder, Dharsono Hartono, who used to work in New York in JP Morgan’s real estate division. Explaining his original reasons for entering the CO2 compensation business, he said:

Suddenly my JP Morgan head blipped and said, ‘This is just like real estate’. If you manage it properly, there will be value, there will be appreciation, you can make money out of it.

In late 2021, Japanese news outlet Nikkei Asia released an investigative report arguing that Katingan had issued credits up to three times more than the amount of carbon dioxide it is likely to absorb. Nikkei claimed that the project had overestimated the deforestation risk the project faced. This is called a “baseline”; essentially, what was likely to have happened in the project’s absence.

These reports have been met with significant pushback.

Another company involved in Katingan, Permian Global, said that Nikkei Asia’s analysis demonstrated “a poor understanding of forest conservation and carbon assessments, while containing many statements that are simply untrue.” Verra also quickly hit back, claiming that Nikkei’s allegations were based on “inaccurate assumptions and irrelevant facts.” A longer statement from Verra in August 2022, said that Nikkei’s reporters had “wantonly, wilfully, and repeatedly parroted an inaccurate and illogical narrative peddled by a few outlier activists whose views run contrary to the preponderance of evidence and scientific thought.”

Verra also came under attack late last year when The Guardian published an analysis that claimed more than 90 percent of Verra’s forest credits were worthless. (For technical reasons, no Indonesian projects were used in the analysis). Verra says the Guardian’s reporting contained “numerous inaccuracies and distortions” and that the academic research upon which it was based was “patently unreliable” because it contained “multiple serious deficiencies”.

Room for improvement

An offset market insider, speaking to MWM on the condition of anonymity, said that the attacks by Greenpeace, Nikkei or The Guardian had some basis in fact but had exaggerated the findings. “Such manipulation points towards a fundamental opposition to market mechanisms, rather than a desire to improve the system,” she said.

She also said that “Carbon Cowboys” – unscrupulous players seeking to cash in on the offsets market – haven’t had much luck in Indonesia as developing carbon projects is much harder than they thought.

Increased focus on baselines, a lack of real understanding around methodologies, and the government’s slow and cautious approach to the regulatory environment have combined to put a brake on fast development, leaving mostly genuine developers in the game.

Nonetheless, she said there was “always going to be greyness” in avoided-deforestation projects, given that they’re based on counterfactual scenarios, and there was always room for improvement in the system. “Handled in a calm and professional manner, the current scrutiny can only be good for the future of genuine developers,” she said, as “anything that protects existing forests, fundamentally has to be good for the planet.”

Does the industry need to tighten up? Yes, it does. Will it tighten up? Yes, it will. From the current industry turmoil more strong and fundamentally sound projects will emerge.

Critics have often highlighted that registries like Verra are paid via commissions from approved projects – US$0.10 per credit certified. Arguably, this means they have a vested interest in seeing them approved. The insider said the emergence of ratings agencies – which are paid by the buyer, not seller, of offsets – would go “a long way towards addressing this issue.”

She also said that if a new analysis demonstrated that a project is likely to be preventing fewer C02 emissions than what it’s selling, then the project methodology will be updated to reflect that. For example, in February this year, Verra announced that its current rainforest protection methodologies are being overhauled.

Verra’s rainforest protection projects reportedly make up around 40 percent of the credits it approves, so it’s a significant overhaul. Nonetheless, until new methods are finalised, the registry is “stand[ing] by all of our current methodologies as the best in class”, a senior Verra executive was quoted by The Guardian as saying.

A burgeoning market

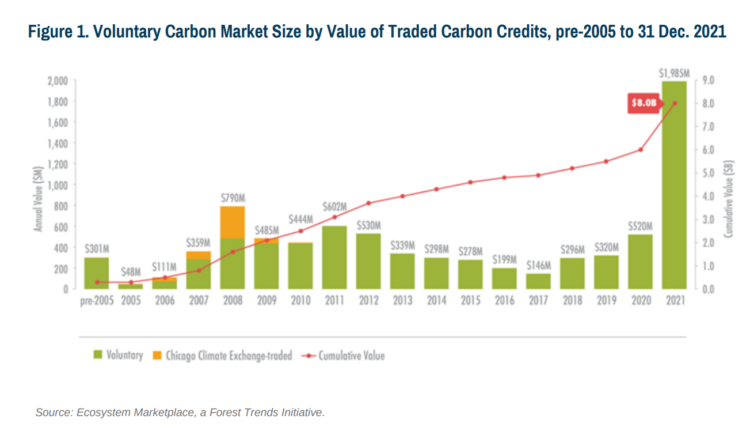

The voluntary carbon market has experienced massive growth in recent years, and is now worth around US$2 billion, according to the latest available figures from Ecosystem Marketplace, an NGO providing information for ecosystem services and payment schemes.

The type of offset that’s seen the most dramatic increase, in terms of total carbon credits issued, has been “forestry and land use” credits – primarily those claiming to reduce deforestation.

Between 2020 and 2021, the total value of all “forestry and land use” credits jumped from $315 million to over $1.3 billion. The offsets category with the second-highest total valuation trails far behind at $479 million in 2021. However, prices for Verra’s rainforest offsets have reportedly dropped since 2021, alongside a slump in demand possibly caused by critical media coverage.

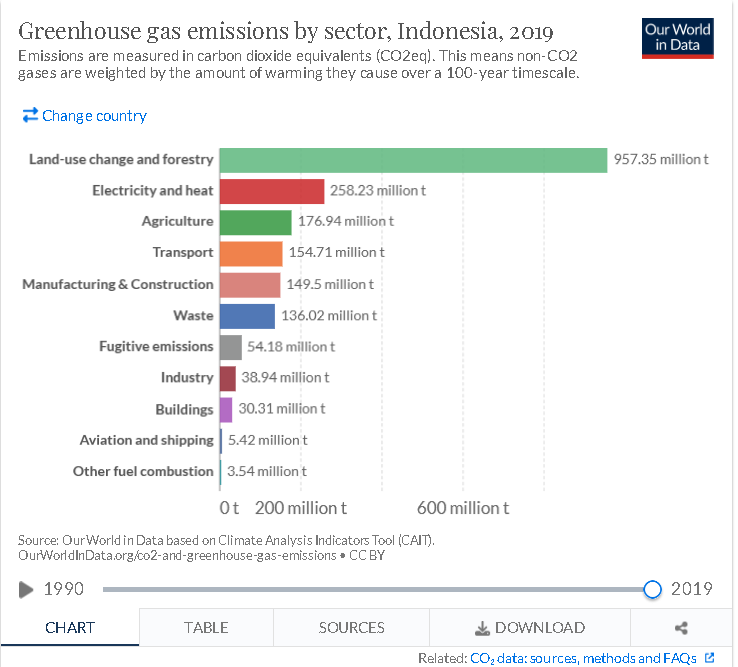

Land use change and deforestation accounts for roughly one fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions. However, in Indonesia land-use change and deforestation are far and away the largest source of emissions: over three times higher than emissions from generating electricity and heat, the second-largest category. Although Indonesia’s deforestation rate is decreasing, large swathes of forests and peatland are still at risk.

This article was edited on the 5/4/2023 after carbon offset ratings agency BeZero informed MWM that Katingan Mentaya has an “A” rating, not a “AAA” rating. The information about a Katingan having a “AAA” rating came from this Verra press release in September 2022: Two Verra Projects in Indonesia Receive High Grades from Offset Ratings Agency – Verra.

Drowning or Waving? Will Beetaloo gas frackers survive Greens, Labor Safeguard deal?

Zacharias Szumer is a freelance writer from Melbourne. In addition to Michael West Media, he has written for The Monthly, Overland, Jacobin, The Quietus, The South China Morning Post and other outlets.

He was also responsible for our War Power Reforms series.

![Planting trees in Indonesia[1]](https://michaelwest.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/photo20credit20wri20indonesia1-e1680582647620.jpg)