Poor productivity growth and persistently strong government spending will give the Reserve Bank no choice but to hike interest rates next week, economists say.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers emphatically denied the government was contributing to a resurgence in inflation, after the Reserve Bank’s preferred quarterly trimmed mean measure came in above its forecast on Wednesday.

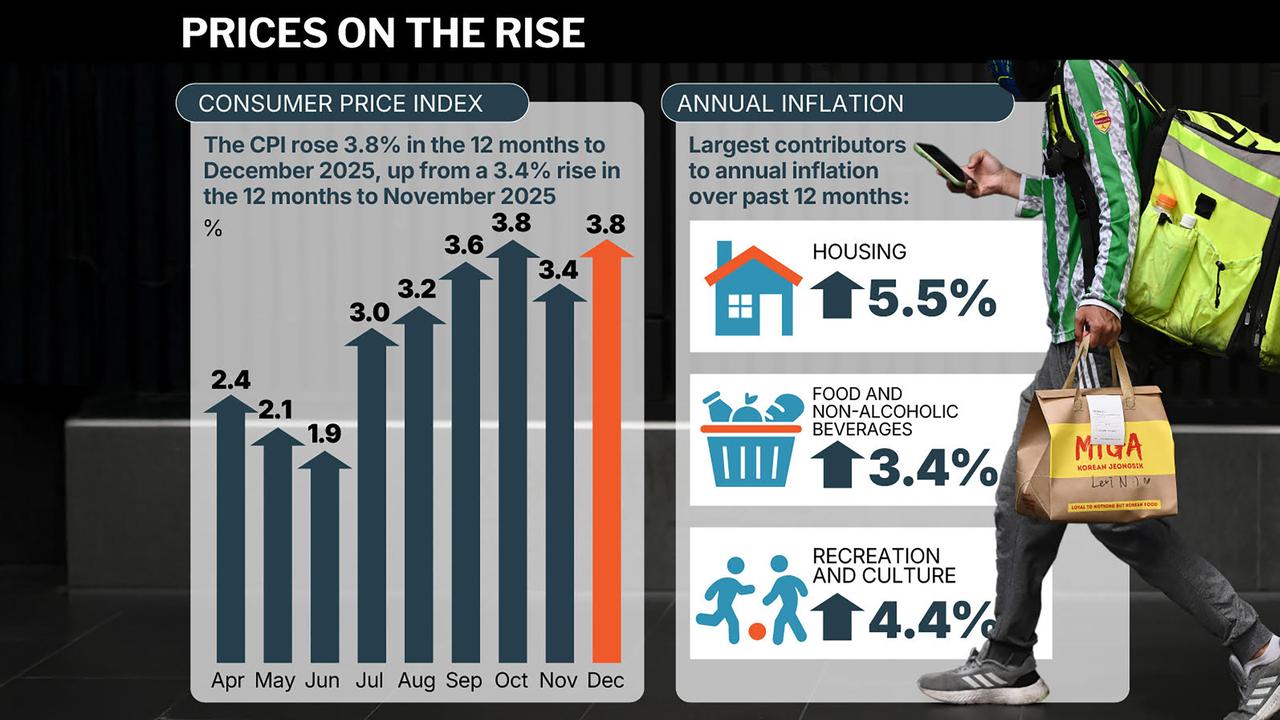

Money markets are pricing in a three-in-four chance of a rate increase on Tuesday after the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported core inflation came in at 3.4 per cent in 2025.

If the inflation spike was down to a temporary lift in a few volatile components such as electricity and travel, the Reserve Bank might be able to write it off as a transient phenomenon and wait it out.

But it was just the latest in a string of recent data showing the economy is running hotter than the central bank expected in November, following strong jobs and household spending figures.

Ultimately, the resurgence in inflation was a result of Australia’s economy running above its speed limit, which has fallen as a result of anaemic productivity growth, HSBC chief economist Paul Bloxham said.

“The question is, how are we going to get the economy to slow down? And the answer is, the RBA is going to have to lift interest rates to make that happen,” he told AAP.

“But it’s not a particularly pleasant story, because the economy is not growing particularly quickly.”

While Dr Chalmers has made boosting productivity growth a priority of this term of government, lifting the economy’s supply capacity will take time.

A good example is the rise of housing costs, with rents up 3.9 per cent and new dwelling costs up three per cent.

The Reserve Bank is particularly considered about the price of shelter, as it makes up a large component of the CPI basket and is stickier than other items.

Demand responds quickly, as evidenced by the surge in applications for the government’s expanded first-homebuyer deposit guarantee scheme.

But supply responds much longer, as evidenced by dwelling completions continuing to lag new home targets.

Shadow treasurer Ted O’Brien laid the blame squarely at the government’s feet.

“While the treasurer is desperate to shift the blame, there is no doubt this Jimflation crisis is homegrown,” he said.

But Dr Chalmers said the rise in inflation was the result of a strong recovery in private spending, not a reflection of public spending.

“Public final demand growth went down, not up, over the past year when it comes to contribution made to our economy,” he said.

But Treasury forecasts government spending will hit 27 per cent of GDP this financial year, which would be the highest level since the 1980s, outside the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even though private demand is gaining strength, blow-outs in public spending were crowding out the private sector, Mr Bloxham said.

AMP chief economist Shane Oliver also said government spending was contributing to higher inflation.

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry policy and advocacy chief David Alexander called for the government to bring public spending to less than 25 per cent of GDP.

Not everyone was convinced that a rate hike was necessary.

Deutsche Bank chief economist Phil O’Donaghoe said there was too much focus on the legacy quarterly trimmed mean, and the statistic bureau’s newer monthly measure revealed a definite downward trend.

“We do not see a compelling case for a rate hike in February,” he said.

Australian Associated Press is the beating heart of Australian news. AAP is Australia’s only independent national newswire and has been delivering accurate, reliable and fast news content to the media industry, government and corporate sector for 85 years. We keep Australia informed.