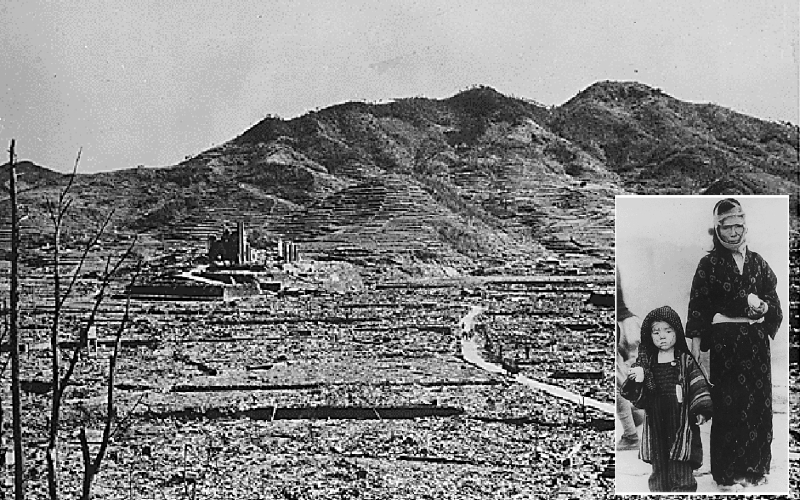

Today marks 80 years since a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. The arms race it started, exposed thousands to radiation from testing. Sue Rabbitt Roff on the history and the calls for compensation.

A recent video shows current UK Deputy Prime Minister, Defence Secretary, Minister for Defence and Minister for the Army fervently supporting calls for financial compensation to the 40,000 Australian, New Zealand and UK ‘participants’ in Britain’s atomic and nuclear test series in the 1950s and 1960s.

The video has been viewed over 5.4 million times, and counting. Made in the years immediately prior to the election of Labour to government, those statements fully conceded all the issues about failures of duties of care by the British government of the day at the Monte Bellos, Emu Field, and Maralinga, as well as Christmas Island.

Prime Minister Starmer may not be able to stave off the pressure much longer.

The evidence of failures of duty of care begins immediately after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A very long fight

Thirty years ago, on the 40th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, I published a book critiquing the studies of the health hazards of the atom bombings. It was based on the almost verbatim records of the meetings of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission established several months after the detonations.

I an interview, James V Neel, a senior geneticist on the ABCC, rapidly became purse-lipped at some of my questions, and I could see the steam rising. Walking me to the steps of the building, he turned to me and said, “If you publish the line you’ve been taking with me, I will sue you.”

I did write the book, but he never sued.

I also interviewed Sir Mark Oliphant in his suburban home in Canberra. Oliphant had lobbied strongly in London and the USA for the development of the first atomic bomb, outlined in the Memorandum written by two refugee physicists – Frisch and Peierls – whom he had brought into the Physics Department at the University of Birmingham.

He spent several years in the USA on the Manhattan Project that built the bombs that were detonated over Hiroshima and then Nagasaki in August 1945.

At the time of our interview, Oliphant was very deaf and began a monologue which did not entertain any interrogation, “like a boxer feinting off any attempts at cross-examination.”

Despite the realisation in the 1950s that there is no dose level below which threshold there will be no radiogenic injury, Oliphant’s opening remark was,

Radiation can’t be all that bad for you.. cosmic radiation, earth radon.. there must be a threshold.

He continued, “I’m not a biologist, though I started out as a medico. I wasn’t interested in people but in things. People bored me stiff. The pettiness of most of medicine is really incredible.”

Maralinga testing

In 1992, Oliphant stated,

“They can really decontaminate Maralinga by leaving it alone. Plutonium alpha particles contamination… I think it has been grossly overplayed. The Aborigines are using it to the full. At the same time, it was very naughty of the British to leave it, and to think of spreading it in that way in the first place was very nasty.”

However, he conceded there were contamination risks.

“At Maralinga, there were UK and Australian biomedical committees. There were lots of shenanigans in connection with it. A biologist named Hedley Marston found trace elements in agriculture – from a biological point of view, he found terrible contamination of large areas of the grazing population. The bomb people were very reticent about revealing contaminatio,n especially regarding food contamination. They hugged that to their chests very closely.”

They were very pig-headed about it. People in control were very haphazard about the dose estimates. People seemed to have great faith in it. People whom I respected. So I accepted it.”

To bomb or not to bomb

Danish theoretical physicist Niels Bohr and others – including Oliphant – tried to persuade President Roosevelt not to use the bomb on Japanese populations. He wrote a letter to President Roosevelt in which he told Roosevelt that he felt this weapon should never be used in civilian cities, should never be used in war, “this should be a weapon for peace, for example, by making an explosion to indicate to the Japanese.”

Roosevelt died, and Truman made the ultimate decision to drop those bombs.

An opportunity missed?

Later, nuclear proliferation became the big issue in the early days of the Cold War. Mark Oliphant also worked with Robert Oppenheimer to persuade Australia’s then Minister of External Affairs, H.V Evatt, to support a Soviet proposal for nuclear inspection at the United Nations during Evatt’s time as Australia’s representative and eventually first President of the General Assembly.

Oluihant recalls, “I went to the meeting of the Atomic Energy Authority of the United Nations in 1946 as the technical adviser to Dr Evatt. I couldn’t stand him; he was a man of intolerable arrogance. Because of the alphabetical order, he was in the Chair of the first meeting of the Security Council and the UN Atomic Energy Commission.”

“The proceedings began, and in those days, there was no simultaneous translation, and when the proceedings opened, the American delegation leader put forward the American policy, and it was clear it was that only America should have nuclear weapons and was the only country that could be trusted. All other countries had to be inspected.”

Russian Foreign Minister, Andrei Gromyko, had a very simple thesis:

- All existing nuclear weapons should be dismantled. He realised the enriched plutonium could be used for reactors;

- All reactors should be subjected to nuclear inspection.

When he was finished, Oppenheimer, who was sitting just behind Oliphant, came round and said to him, “Look here, you and your boss need to have a serious discussion because here we have the Russians seriously proposing nuclear inspection.” Oliphant says, “I went down to Doctor Evatt and told him Robert had been down to see me, and we both felt very strongly.” Doctor Evatt said,

Nonsense, nonsense. We might want to use them against them.

Australia’s victims

Oliphant was right about several things. Contrary to the received narrative that Menzies was conned into permitting the development of atomic and then components for thermonuclear weapons in Australia, the Prime Minister was lobbying for tactical weapons for Australia from the outset.

A file in the UK National Archives titled Nuclear Capability in Australia (DEFE/2148) shows that Menzies was very alarmed at the possibility of Australia being subjected to monitoring because it had complied so closely with the British demands that

it stood in danger of being designated a nuclear state.

Oliphant was also right that throughout the 1950s it was very naughty of the British to leave it [radioactive contamination] and to think of spreading it in that way in the first place was very nasty.

The evidence of that statement and the health consequences for the 40,000 servicemen, of which a quarter were Australian, plus scientists, civilians, and the indigenous and settler population of Australia, is now being released by the UK government. But as yet, with no funding to download the half million documents or to analyse them.

Meanwhile, the current Minister of the UK Armed Forces, Luke Pollard, conceded in a BBC radio interview during Armed Forces Week on June 25, 2025:

‘We know the consequences for many of those people participating in the tests are carried, not just by individuals, but by their family members. That’s why we want to work out what we can declassify and share, and get to the heart of trying to get justice for those individuals.”

More than a third of the documents of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear (sic) Tests in Australia that the National Archives of Australia holds are still marked ‘not yet examined. That would be a good place to start.

Let’s hope it doesn’t take another seventy-five years.

Finally compensation for victims of Australian atomic bomb testing?

Sue Rabbitt Roff studied and taught at Melbourne and Monash Universities. Her recent writings on cultural aspects of settler colonial Australia have been published in Meanjin, Overland, the Conversation, the Independent and on Pearls & Irritations. She is currently writing a revisionist history of British atomic tests and nuclear trials in Australia.