Few do pomp and ceremony as well as the Chinese.

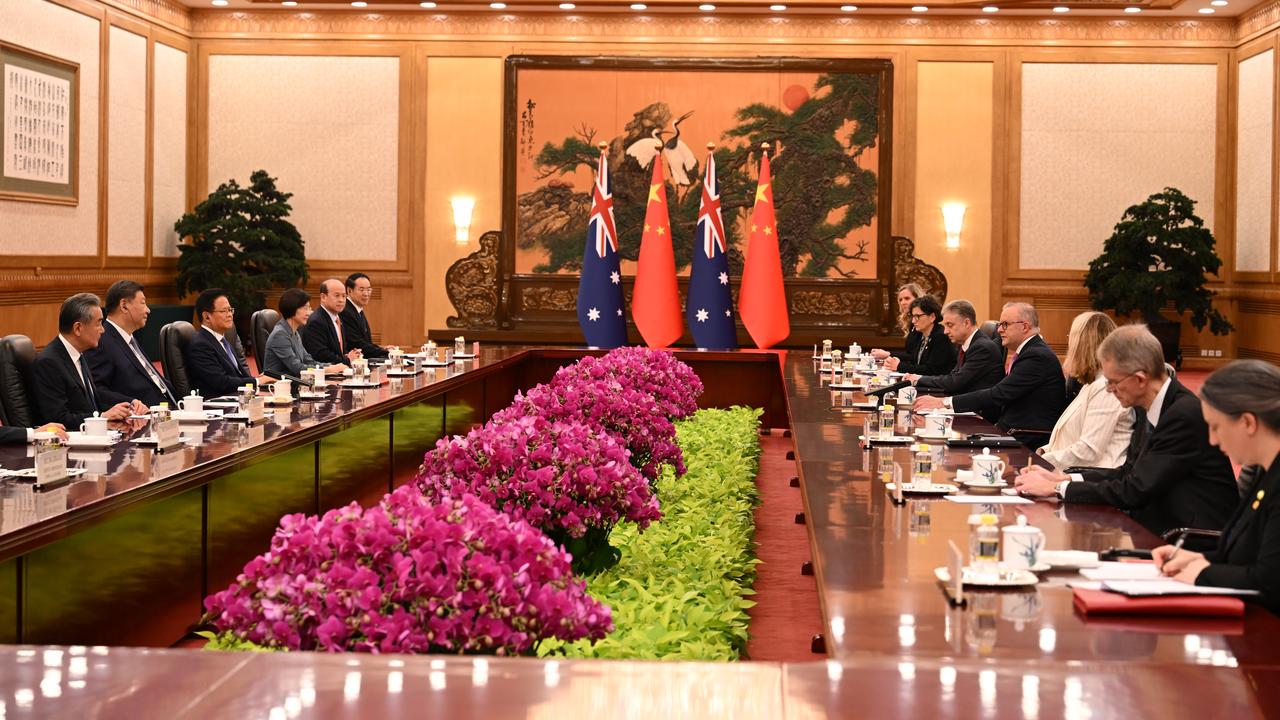

As he met with leaders in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on Tuesday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was given the red carpet treatment.

Rows of immaculately decorated soldiers were wheeled around the hall in perfect synchronicity and a People’s Liberation Army brass band played Chinese covers of Aussie pub rock classics by the likes of Paul Kelly and Midnight Oil.

The lavish display may be par for the course for world leaders ushered into the grand neoclassical sanctum of Chinese power.

But the warm reception to the prime minister’s six-day trip of China and gushing praise heaped upon him was notable in the highly choreographed world of Chinese political theatre, where symbolism and ritual are key.

Protocols matter, says Associate Professor Graeme Smith, an expert on Chinese politics at the Australian National University.

“All foreign policy, but particularly for China, is for a domestic audience,” he tells AAP.

“This is not about us. It’s about citizens, about Chinese Communist Party members. That’s what these are for and we’re just a nice prop for them.”

The constant refrain of co-operating where they can, disagreeing where they must and engaging in the national interest was calibrated to chime with Beijing’s own goals.

Focusing on moving the relationship forward gave them an out for their unilateral decision to torch relations in 2020 while allowing them to save face.

The unusually long duration of the prime minister’s trip and the fact it occurred so soon after being re-elected, was interpreted by both sides as a sign of the importance of the two nations’ relationship.

Likewise, Mr Albanese remarked that the length of the meetings he had with President Xi Jinping, Premier Li Qiang and National People’s Congress Chairman Zhao Leji was a sign of “respect” – a word he would keep coming back to through the course of his trip.

“I had meetings for around about eight hours yesterday,” he said at the Great Wall on Wednesday.

“It was a very long meeting but it also showed respect to both sides, the fact that President Xi didn’t just have a meeting but we had a lunch where President Xi as well invited Jodie to attend.

“That lunch was a sign of respect to Australia, to our country.”

The fact the military band at the leaders’ meetings learned to play songs specifically chosen to suit the prime minister’s taste showed the effort they were willing to put in.

“Those gestures matter, respect matters between countries,” he said.

“The opportunity to sit down and have a meal and talk about personal issues, talk about things that aren’t necessarily heavily political, is really important part of diplomacy.

“One of the things that my government does is engage in diplomacy. We don’t shout with megaphones.”

The contrast to the way the US conducts diplomacy under Donald Trump couldn’t be more stark.

The US president was a constant elephant in the room during the trip.

From his first day in Shanghai, Mr Albanese’s visit was almost derailed after it emerged Pentagon strategist Elbridge Colby had been pressuring Australian and Japanese diplomats to provide assurances about joining the US in a hypothetical conflict with China over Taiwan.

But Mr Albanese refrained from engaging in the transactional style of diplomacy his American counterpart trades in.

When the opposition criticised him for failing to bring back tangible results and “indulgent” visits to the Great Wall and a panda research centre, the prime minister said they were missing the point.

“The Great Wall of China symbolises the extraordinary history and culture here in China and showing a bit of respect to people never cost anything,” he said

“You know what it does? It gives you a reward.”

Patient, consistent diplomacy is the government’s modus operandi.

Tracing the footsteps of Labor leader Gough Whitlam along the Great Wall was a powerful bit of symbolism, Prof Smith says.

Mr Whitlam visited the wonder in a landmark trip as opposition leader acknowledging communist rule of the People’s Republic of China in 1971, becoming one of the first Western politicians to do so.

It sent a clear message about the enduring strength of the relationship, Prof Smith says.

“This is probably one of the strongest cards we’ve got to play in terms of the relationship, that we were a first mover in recognising China. That gets us a lot of points.”

Premier Li praised Mr Albanese for his personal role in mending Sino-Australian relations in their meeting on Tuesday.

Chinese state media, which poured endless scorn on Australia when relations were at their lowest, was glowing in its coverage of Mr Albanese, casting the previous coalition government as the source of the conflict.

“In recent years, as China-Australia relations have continued to improve, the Australian government’s understanding of its relationship with China has also deepened,” according to an opinion piece in Chinese state-owned tabloid the Global Times.

“(Mr Albanese) has demonstrated a pragmatic and rational approach to China policy.

“Today’s China-Australia relationship is like a plane flying in the ‘stratosphere’ after passing through the storm zone and the most turbulent and bumpy period has passed.”

Australian Strategic Policy Institute executive director Justin Bassi says the prime minister’s visit was positive for economic relationships and trade.

But the approach is not without its risks.

“I think here the risks are threefold,” he told ABC News.

“I think there is a risk that we are used for propaganda purposes. There is a risk that … trade becomes an over-dependency and the third risk is that we provide a perception, both to China and to our own public, that short-term economics are outweighing long-term security.”

Australian Associated Press is the beating heart of Australian news. AAP is Australia’s only independent national newswire and has been delivering accurate, reliable and fast news content to the media industry, government and corporate sector for 85 years. We keep Australia informed.