Everything about AUKUS nuclear waste is a political secret, including the cost, which will more than double the $368B announced AUKUS price tag. Former submariner Rex Patrick with the story.

If we ever get these subs, the total price tag may well be over $1 trillion. I’m in the Federal Court at present, trying to pry open a November 2023 report into how the Government intends to deal with the high-level nuclear waste from AUKUS submarines.

But there’s already a lot we can deduce by combining what has been extracted from the Government using Freedom of Information (FOI) laws, from Senate testimony and also looking at how the United States does and doesn’t take care of its naval nuclear waste.

Cost explosion

For starters, there was a short but insightful exchange in Senate Estimates last year between Senator Lidia Thorpe and the head of the Australian Submarine Agency (ASA), Admiral Jonathon Mead.

After making quick reference to the cost of nuclear waste facilities overseas, Senator Thorpe asked about the waste costs for AUKUS, “There’s no costing as yet; is that right?” Mead responded, “That’s correct”.

For an organisation that is required to cost its capability from cradle to grave, including support facilities, it’s a huge omission. It might be the case that

they’re too frightened to do the math.

As I will set out below, the price of safely storing AUKUS waste is likely to double the AUKUS price tag. But first, we need to take a look at what radioactive waste AUKUS will produce and what will be done with it.

Low-level waste

We know that Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines will produce small amounts of low-level waste every year (disposable gloves, wipes, reactor coolant and Personal Protective Equipment). ASA Senate Estimates briefs obtained under FOI suggest that this will amount to “roughly the volume of a small skip bin each year.”

This, along with low-level waste from US and UK submarines operating out of Perth, will be stored at HMAS Stirling until the Australian Waste Management Agency builds and commissions the National Radioactive Waste Management Facility.

Barely noticed by the national media, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works approved the construction of a ‘Controlled Industrial Facility’ at HMAS Stirling in August 2024.

High-level waste

When each AUKUS submarine decommissions, Australia will need to handle the recovery, transport, storage and disposal of two different types of high-level nuclear waste: spent nuclear fuel, about the size of a small hatchback, and the reactor compartment, about the size of a four-wheel drive.

Noting the total lack of transparency around Australia’s plans, MWM is making a reasonable assessment as to how this waste will be handled by looking to the US.

Fuel rods will be removed from the submarine at a decommissioning yard (possibly Henderson in WA for the Virginia Class and Osborne in SA for the SSN-AUKUS submarines).

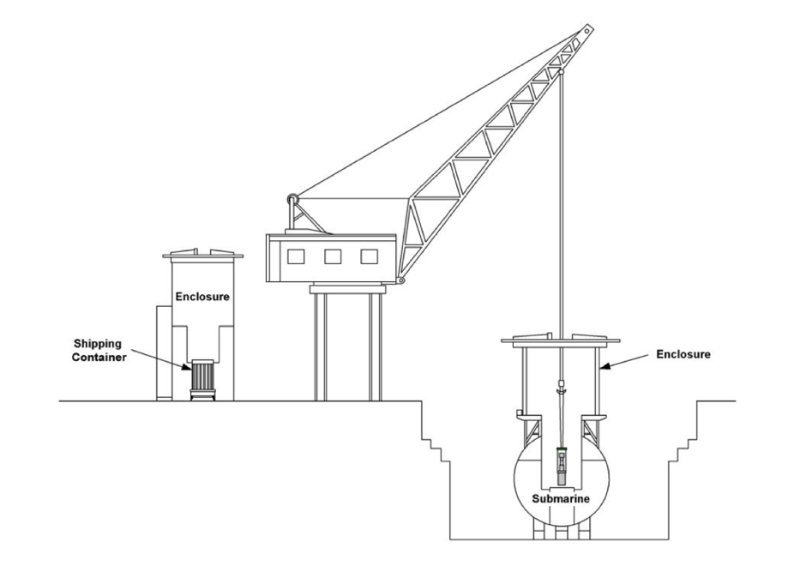

Submarine de-fuelling (Source: US Department of Defense)

The hull is cut open, and a defueling enclosure is installed on the submarine to provide a controlled work area. The fuel is removed into a shielded transfer container and moved to a wharf enclosure. It’s then placed into a specially designed shipping container for transfer to, in the case of the US, an intermediate ‘storage site’ in Idaho. Despite 70 years of nuclear-powered submarine operations (USS Nautilus was commissioned in 1955), the US has not yet sorted out its long-term ‘disposal site’.

It is not clear whether Australia will have an intermediate ‘storage site’ and a ‘disposal site’ or a combined site. Certainly, both storage and disposal are talked about in the information that has been released under FOI.

Australia is not permitted, by the text of the AUKUS Treaty and by commitments made to the International Atomic Energy Agency, to reprocess the fuel. Reprocessing involves separating the plutonium and fissile uranium from the spent fuel to reduce the amount of spent fuel that needs to be stored long term, but doing so raises nuclear weapon proliferation concerns.

For Australia, we have to find a geologically suitable place to bury the fuel in the state it was when it left the submarine. Whilst the Defence Minister has declared this will be on ’Defence land’, the ASA can identify a news site and the Minister can compulsory acquire it – anywhere in Australia.

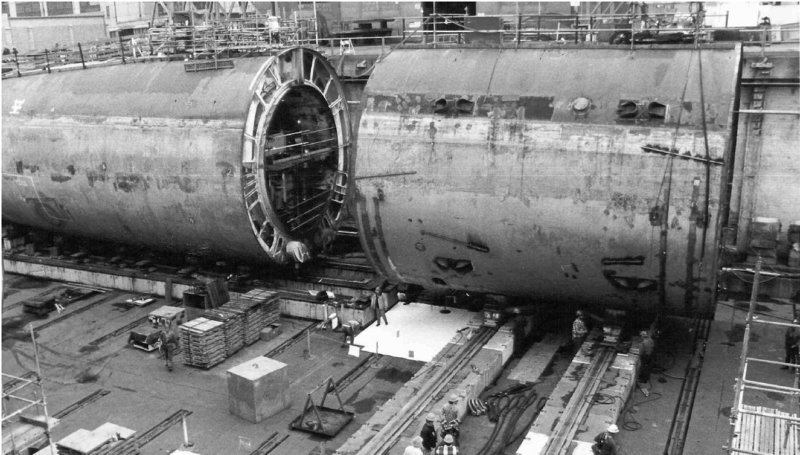

Reactor compartment

To deal with the reactor compartment, all of the elements of the reactor that will remain in the compartment – the pressure vessel, piping, tanks and fluid system components – are drained to the maximum extent practicable. About 2% of the liquid remains trapped in discrete pockets.

All openings are then sealed.

The reactor compartment is then cut from the submarine, and with the pressure hull remaining as part of the disposal package, the high-strength steel serves as an outer seal.

Reactor Compartment Separated (Source: US Department of Defense)

In the United States, the reactor compartment is transported to “Trench 94” in Washington state.

It is not yet known whether the Australian Government will bury the reactor compartments in a final disposal site.

Looking after high-level nuclear waste is complex. You can’t responsibly just bury it or dump it in a deep mine shaft.

Nuclear waste facility

A waste facility must be carefully located, away from seismic activity, away from flooding and other weather events and generally where geological structure allows for deep, very long-term storage. Geoscience Australia has looked at suitable locations for a high-level radioactive Waste store on occasions between 1976 and 1999 (subject to a National Archives request).

It must also be located with suitable transport pathways from the submarine dismantling yard or possibly several yards.

The site must be prepared and built/bored. It must have access to electricity supplies, water, communications and sewerage. It must allow for the safe receipt and storage of fuel and the reactor compartments, it must be resilient to loss of heating or ventilation, loss of electricity, flow blockages, structural failures, etc.

It must be resilient for well over a millennium.

It must also be designed with the necessary security in mind, with access control, constant monitoring, intrusion detection and central alarms in place, and be secure in relation to protest and sabotage and have a co-located response capability. It must provide for safe long-term storage, with multiple barriers in place to prevent release of radioactive material, and be designed to deal with large accidental radioactive releases.

At the same time, the facility will be subject to international non-proliferation safeguards overseen by the International Atomic Energy Agency, which will require periodic access and perhaps remote monitoring and surveillance.

It will likely need a level of remoteness, but be able to be staffed by relevantly qualified personnel, and to receive surge responders in the event of an emergency.

Design and construction would take close to ten years.

What will it take?

The Government has committed to consultation as it selects a site for long-term disposal, yet the law does not require it.

The decision to locate a National Radioactive Waste Management facility at Kimba in South Australia involved a lot of communication, some consultation, but very little listening. The Federal Court ultimately found that the decision-making process for that site was seriously flawed. The Liberals get a D minus.

Labor got the Parliament to declare both HMAS Stirling in Perth and the shipyard precinct at Osborne in Adelaide a ‘designated zone’ for nuclear activities. There was no consultation, so they get an F.

Section 10(2)(c) of the Australian Naval Nuclear Power Safety Act 2024 allows the minister to designate more zones. The consultation can be of a ‘tick-the-box’ nature.

AUKUS waste plans. The hitchhiker’s guide to nuclear approvals

While we don’t know what the cost of an underground storage/disposal facility would be, documents released under FOI show that a 2019 cost estimates study by Altus Expert Services placed the cost of an above ground facility at Kimba at $923 million. We could reasonably expect a deep storage facility could cost billions.

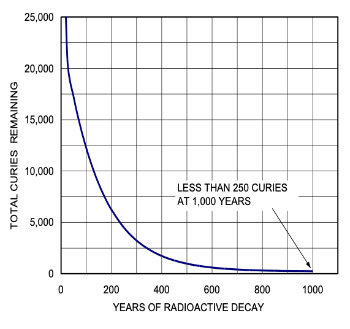

Radioactivity in a Reactor Plant v Time After Final Operation – (Source: US DoD)

Then there are the ongoing operational costs of the facilities, over several hundred years.

Even at an annual cost of only $30 million per annum, that’s close to $4B over 120 years. And if the site is then sealed for 100,000 years, as the Finnish intend to do with their underground facility, there’s even more cost. Even if monitoring of sealed waste only cost 1/10th of the yearly operating cost, say $3million, the cradle-to-grave cost of dealing with AUKUS high level waste will add up to more than $300 billion; $300B that seems to have slipped ASA’s minds.

One thing’s for sure, there’s been too much secrecy around this radioactive hot potato. Maybe things will fall my way in the Federal Court. But it would be much better if the Government was just be up-front with everyone, particularly as we tax-payers have to pay for it.

Rex Patrick is a former Senator for South Australia and, earlier, a submariner in the armed forces. Best known as an anti-corruption and transparency crusader, Rex is also known as the "Transparency Warrior."