It’s been a 60-year quest to take Timor’s oil and gas. An invasion didn’t get it. Spying didn’t get it. So now Australia is waiting them out. Former senator Rex Patrick reports from the streets of Dili.

In 1969, Australia granted five exploration permits for petroleum over parts of the seabed in the Timor Sea that lay closer to the coast of Portuguese Timor than to the coast of Australia. Portugal formally protested, but events overtook things.

In April 1974, a political revolution in Lisbon spelled the end of Portugal’s colonial empire. Portuguese Timor’s independence was now on the agenda. With an eye to the extensive reserves of oil and gas in the seas between Australia and Timor, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs assessed, “the Indonesians would probably be prepared to accept the same compromise as they did in the negotiations already completed on the seabed boundary between our two countries. Such a compromise would be more acceptable to us than the present Portuguese position.”

Maritime Boundary

Let’s pause for a moment and look to maritime boundaries and petroleum.

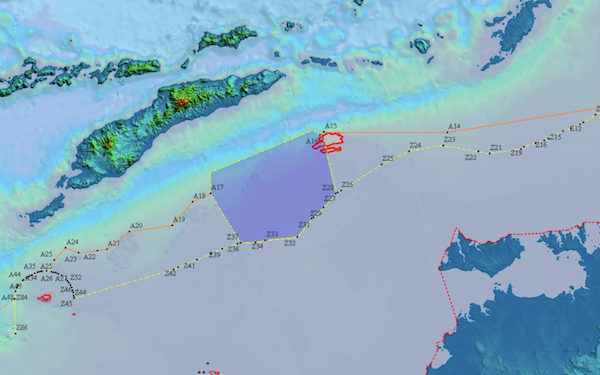

Referring to Figure 1, it can be seen that in 1972, Australia negotiated a seabed boundary with Indonesia (the black line) that was much closer to Indonesia than Australia. Indonesia agreed to this in exchange for Australian support in the international arena for the acceptance of archipelagic seas, which gave Indonesia control of the waters in-between its thousands of islands.

Remarkably, or perhaps unremarkably, the oil and gas deposits of Corallina, Laminaria, Kitan, Bayu-Undan and Greater Sunrise were on the Australian side of the seabed boundary.

The problem was, if international norms were adopted, an independent Timor would claim a median line boundary encapsulating all of the oil and gas that Australia wanted.

Invasion

An Indonesian takeover of Portuguese Timor soon had its advocates in the Department.

On 6 September 1974, Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam met with Indonesia’s President Suharto and offered support for Timor’s incorporation into Indonesia, even though the Timorese were entitled to and desired self-determination.

On 7 December 1975, Indonesia launched a full-scale military invasion of Timor. Australian diplomats shielded Indonesia from criticism at the United Nations.

In the ensuing decade and a half, 204,000 Timorese people, a staggering 31% of East Timor’s population, died of famine, cholera, tuberculosis and resisting the Indonesians.

Australia did not support UN General Assembly resolutions in favour of East Timor’s self-determination between 1976 and 1981. Instead, in February 1979, Australia gave de jure recognition to Indonesian control over the territory and began negotiations with Indonesia over the seabed boundary with East Timor, although Indonesia refused to accept the same compromise over the Timor Gap as it had in the 1972 Seabed Treaty. A decade of negotiations ensued, resulting in the Timor Gap Treaty in 1989, which allowed both countries to exploit the energy resources of the Timor Sea.

Never mind the humanitarian catastrophe inflicted on the Timorese; the focus was on the sea, or rather what lay beneath.

No Independent Umpire

Under the strain of the 1998 Asian Financial crisis and after the resignation of President Suharto, Indonesia agreed to grant the Timorese a referendum: they could choose special autonomy within Indonesia or independence. The referendum was held on 30 August 1999 under the auspices of the United Nations. 78.5% of registered voters opted for independence from Indonesia.

Under mounting international pressure, Indonesia withdrew from Timor after destroying much of its infrastructure and deporting 250,000 East Timorese across the border to West Timor. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 1264 on 15 September 1999, authorising a multinational force to restore peace and security in East Timor, led by Australian Major-General Peter Cosgrove.

While Australian troops were doing a great job on the ground in Timor, our diplomats and spies were busy engaging in an oil and gas heist.

Timor-Leste was to become an independent state on 20 May 2002. Knowing that a new maritime boundary treaty had to be negotiated, and Australia’s argument to maintain its claim over Timorese oil and gas reserves was weak, Australia immediately withdrew from the maritime boundary jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea.

There was to be no independent umpire for Timor to go to.

Well aware of Timor’s financial predicament, Australia’s foreign minister, Alexander Downer, set the negotiation ‘mood’, telling the Timorese, “We don’t have to exploit the resources. They can stay there for 20, 40, 50 years. We are very tough. We will not care if you give information to the media. Let me give you a tutorial in politics – not a chance.”

And Now for Some Spying

Then, having agreed to negotiate in good faith, Australia had the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) spy on the Timorese negotiation team. Under the cover of an aid project, ASIS installed listening devices in Timor’s ministerial offices. The spying operation provided Australia with secret access to Timor’s internal deliberations and negotiating positions.

“Admit it, and move on”: Rex Patrick on Australia’s East Timor spying

The compromised Timorese negotiating team signed a Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS Treaty) in 2006.

The final ratified arrangement, as of 2007, saw Australia get 10% of revenues from oil and gas in the Joint Petroleum Development Area (the purple area in Figure 2) and 50% of the revenue from Greater Sunrise (marked in red in Figure 2).

Facilities were built at Darwin to liquefy the gas from the fields, for export to North Asia.

Caught Out

But Australia’s fraudulent conduct ultimately came to light. Timor’s government found out about the spying and took Australia to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague to have the Treaty voided.

After unsuccessfully raising six objections to compulsory conciliation, Australia was forced by a combination of legal and diplomatic pressure to renegotiate and sign a new ‘Treaty Between Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Establishing their Maritime Boundaries in the Timor Sea’.

The new Treaty entered into force on 30 August 2019, opening the way for Timor-Leste to secure 80% of Greater Sunrise’s revenue if the gas is processed in Darwin or 70% of the revenue if the gas is processed in Timor.

Tasi Mane

Timor’s Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao has a vision for uplifting his country – processing gas on its southern shores. His ‘Tasi Mane’ project is to bring revenue and economic activity to Timor, including direct technical, engineering, project, transport, logistics and administrative jobs, as well as indirect jobs for teachers, health workers, caterers and baristas.

It’s a bold plan that has the support of the Timorese people.

But it’s not what the Australian Government wants. Australia’s priorities are elsewhere. It wants to be a reliable supplier to energy-hungry petroleum exhausted Japan, South Korea, China and Singapore in return for other economic interaction and favours. It has the North West Shelf and Ichthys projects, amongst others, online and delivering on exports.

Climate Betrayal: how backroom deals with Japan locked Australia in for decades of gas

Santos’ Barossa field is next, but in order for the company to meet its carbon abatement obligations, it needs to store CO2 from the field somewhere. That somewhere is Timor’s Bayu-Undan field. The Timorese aren’t keen to do this, but may have no choice. Their preference is to instead use well well-established enhanced oil recovery technique to extract gas still present in the field.

But while Greater Sunrise is not producing, there’s no money coming into the Timorese treasury. Australia’s delays on Greater Sunrise is turning into a forced cash-for-carbon scheme.

An Unwanted Report

In April 2024, Australia and Timor commissioned a company, Wood Australia, to consider Greater Sunrise processing options. Up until the report was delivered to both Governments, work behind the scenes to agree on a Production Sharing Contract, Petroleum Mining Code, and fiscal regime was progressing well.

When the report dropped, suggesting the better economic outcome was to process Greater Sunrise in Timor, negotiations turned into a go-slow. Downer’s ‘wait forever strategy’ has come back into play.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade have been working on bringing Timor’s resources back to Australia for sixty years. Why stop now?

Suffer the Timorese!

China and national security stupidity

Meanwhile, as Timor struggles economically, China is stepping up to the plate, offering the Timorese assistance and building infrastructure (freeways and ports) as part of its Belt and Road strategy.

None of the Timorese that I talked to on the streets of Dili want Chinese help over Australian help. But the latter is not on offer.

In 2019, the Australian Government actively forced the shutdown of a safe Timor Sea petroleum extraction operation working out of Suai on Timor’s south coast (they did so without involving the Timorese, even though the field that was being pumped straddled the maritime boundary – something Timor didn’t know). Australia didn’t want an exemplar building confidence and capability to underwrite Tasi Mane.

As an aside, Australia has taken possession of the Northern Endeavour vessel, the only vessel that could realistically give Timor a further extraction option for Bayu-Undan, and is in the process of scrapping it.

Meanwhile, the Chinese fill the void. In 2024, while the Australian Government was collecting taxpayers’ coins to gift to the US for AUKUS submarines it could take to the South China Sea, Chinese navy vessels were pulling in for rest and recreation in Dili.

With help from US President Trump shutting down USAID, China is seeking to fill the development assistance void, working to create a Timorese dependence that will result in disaster for Timor if the Chinese eventually decide to walk away. China knows it, and so does Timor.

At some near future point, Timor, without income from Greater Sunrise, may well have no choice but to ‘offer’ to house a Chinese Air Force base on its soil; Australia won’t get its US submarines, but China may well get a stationary aircraft carrier 700 km from Darwin.

Well done, DFAT. What fools!

Rex Patrick is a former Senator for South Australia and, earlier, a submariner in the armed forces. Best known as an anti-corruption and transparency crusader, Rex is also known as the "Transparency Warrior."