Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock last week set out to kill expectations of an interest rate cut. She succeeded, but that doesn’t mean a cut isn’t coming. Michael Pascoe reports.

Here’s the thing about Reserve Bank interest rate guidance: the RBA will downplay the chance of an interest rate cut right up to the minute it cuts them – and even then, it will warn it might put them up again.

RBA Governor Michele Bullock last week achieved her goal of scaring the horses about a possible interest rate rise. The commentariat (almost) universally swallowed it, and according to the Westpac/Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment survey, the public did, too.

“There is a sharp decline in the sentiment reading after the RBA’s decision, down from 89.0 pre-release to 82.0 post-release,” Westpac said. “The RBA’s emphasis on maintaining restrictive monetary conditions to bring inflation towards the target range, or the absence of any guidance on easing conditions, might have been a factor behind the sharp decline in consumer sentiment post-release.”

And that sort of thinking isn’t doing the Albanese Government any favours.

The reality is that the RBA board considered lifting rates last week the same way I consider what I will do winning PowerBall. You can consider it, but it’s not going to happen.

And as for the Governor’s “I’m not giving forward guidance, but here’s some forward guidance” performance, ruling out a rate cut in the next six months, that was nonsense, too.

If the data keep heading in the direction they’re heading, a rate cut will not be off the table at the meeting in six weeks’ time and by the November meeting it will certainly be “live”.

The inflation hawks calling for higher rates are looking backwards, the doves are looking forwards. Given the very lagged nature of monetary policy, the bets need to be made on the future.

Reserve Bank inflation backflip as Bullock disses Chalmer’s CPI reduction

No preempting of cut

Ms Bullock was merely doing what RBA governors do aside from moving interest rates: jawboning the market. The bank didn’t want the market pre-empting its eventual move, so it gave the distinct impression there isn’t one in the offing.

This is the reverse of what Philip Lowe was pilloried for – increasing rates after he gave the distinct impression there was no increase anywhere on the horizon. The media and public will be more forgiving of a change of mind about a rate cut than a rate rise.

The governor kept her outlook simple to achieve her purpose. There was more subtlety tucked away in the quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) for those who cared to look for it.

For a start, there was further confirmation that the last rate rise, nine months ago, still hasn’t fully worked its way through the system. The RBA guesses the poor devils taking most of the pain for the team – the average household with a mortgage – will feel more pain by the end of the year if rates don’t move. Required mortgage servicing will take another 15 points of all households’ disposable income by the end of the year – and remember, only about a third of us have a mortgage.

So tell the hawks demanding tighter monetary policy that it’s still tightening.

And then there’s the little matter of the bank already having achieved the old NAIRU (the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment), not that the RBA wants to talk about NAIRU anymore – it’s too embarrassing and apparently doesn’t mean anything now.

The bank has never known what the NAIRU was at the time – it was a somewhat mythical thing only recognised in retrospect. Previous guesses kept being proven wrong as the unemployment rate came down without accelerating inflation.

Inflation pressures easing

The bank admits the present unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent isn’t “accelerating inflation”. It doesn’t take much of a look at the details of the CPI to see wages aren’t driving the key inflation problem areas.

What the bank wants (but doesn’t spell out) is that it wants an IDRU – an Inflation-Decelerating Rate of Unemployment. It now talks of “full employment” – a euphemism – alleging that the labour market must be too tight because, well, inflation isn’t coming down fast enough. You know, more demand than supply sorta stuff.

The RBA deputy governor, Andrew Hauser, delivered a rather candid speech on Monday, admitting how poor the RBA and everyone else is at forecasting and how the bank tries to learn from its mistakes. (The revisions from the May SMP to the latest edition illustrate the RBA understandably isn’t too sure of what’s actually happening now, let alone in several months’ time.)

Looking for a reason for inflation being “stickier” than it had forecast, the bank has come up with the theory that supply is weaker than it realised. Admitted Mr Hauser:

“Now, it is one thing to hypothesise weaker supply, it is another to quantify it. And that’s because supply is not directly observable: it is a classic latent variable. So any estimate is subject to huge uncertainty.”

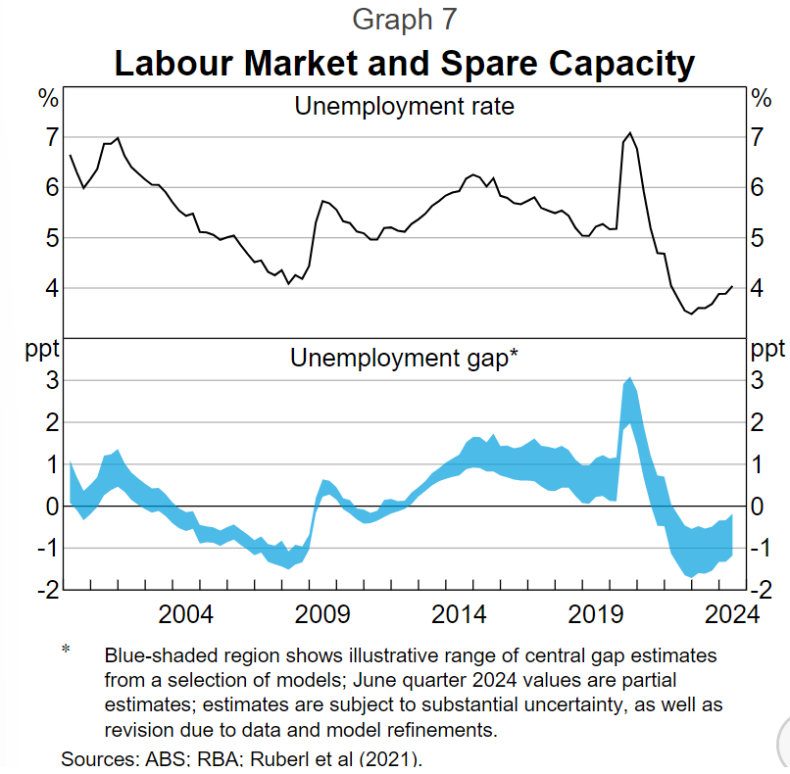

So the economists crank out all the models they can think of to make various guesses for them and figure that, hey, somewhere in the range must be the answer. Specifically in regards to the labour market, the banks’ modellers came up with Graph 7, showing the range of space capacity estimates.

That range looks like the bank’s models want somewhere between zero-point-fraction and one-point-fraction per cent higher unemployment – say, 4.3 to 5.3 per cent – to balance supply with demand. What a happy thought.

Mr Hauser himself doesn’t sound too convinced by the exercise, however:

“It must be said, however, that these changes in assumptions are tiny relative to the huge true range of uncertainty over these measures. So we have to be humble about our confidence in this judgement: spare capacity could easily be much higher or much lower.”

To put it more succinctly, they simply don’t know. Despite that, the bank’s forecasts show the board is shooting for a 4.4 per cent unemployment rate as the answer. Thus it is RBA policy to persecute several thousand more of the innocent who have no role in keeping inflation higher than desired.

Wages growth abating, too

Meanwhile, Tuesday’s wage price index printed with a June quarter rise of 0.8 per cent following a March quarter rise of 0.9 per cent i.e. an annualised rate of 3.4 per cent over the first half of this year and while the CPI on the same basis was 4 per cent.

Don’t blame wages growth for inflation. Not only have we achieved NAIRU, we might well have IDRU.

Looking ahead to the annual figure, the high 2023 September quarter WPI rise of 1.3 per cent will drop out. That figure included a 5.75 per cent Fair Work Commission increase in award wages – this quarter, the increase is just 3.75.

So why was Governor Bullock and Co jawboning so hard? Partly to get as much mileage as possible out of the present restrictive rate, partly because of what was spelt out in the SMP’s “Box A: Are Inflation Expectations Anchored?”

The bank is, therefore, quite chuffed to show the money market, and the consensus of market economists to believe not only that it is fiercely determined to get inflation down to 2.5 per cent but also that it will actually achieve that ambition.

The latest SMP stated:

“Inflation expectations are the rates of inflation that people expect over some future horizon. These matter because actual inflation partly depends on what people expect it to be and build into their wage- and price-setting behaviour. We consider inflation expectations to be ‘anchored’ if they are stable at a level that is consistent with inflation being maintained at the midpoint of the target band (2½ per cent) over an appropriate period.”

The expectations are presently anchored, so keep ‘em believing, talk tough, hose down any signs of pre-emptive softness on rates and the job is half done.

And if there’s a little misleading going on…well, that’s part of the job.

PS> Also missed by nearly everyone, the RBA has downgraded its expectations for dwelling investment both this financial year and next. Not to put too fine a point on it, the RBA reckons Albanese’s “one million new homes in five years” is shot, let alone that fairytale 1.2 million “stretch target”.

No rainbow. Government’s housing rhetoric laid bare by RBA decision

Michael Pascoe is an independent journalist and commentator with five decades of experience here and abroad in print, broadcast and online journalism. His book, The Summertime of Our Dreams, is published by Ultimo Press.