Australia’s homeless may not get the headlines, but they are the face of our housing crisis, including those in ’emergency accommodation’. Andrew Gardiner reports.

According to the 2021 census, there were 122,000 homeless people in Australia, including people sleeping rough, couch surfers, those in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings, and those in boarding houses and other temporary dwellings for the homeless. Some of the latter are found in places like Scotty’s Motel outside Adelaide.

Scotty’s Motel, guarded by its ‘Big Scotsman’, is a much-loved local landmark. Frequented since the ‘60s by travellers, truckies and, yes, the odd amorous couple. What would they, and neighbours in the leafy surrounding suburb of Medindie, think of what it has become?

Nowadays, Scotty’s is a haven for downtrodden, traumatised souls forced into Emergency Accommodation (EA); domestic violence victims and their children, tenants forced to flee violent neighbours, a lucky handful of SA’s estimated 7,410 homeless people transitioning to public housing and a smattering of ex-prisoners.

You read that right, children and ex-prisoners thrown together in an area slightly larger than the average Medindie house block. Society’s flotsam and jetsam, crammed into 53 rooms amid screams, scuffles and self-harm as broken systems battle a scarcity of homes to put them in.

Medindie locals grumble about what they loosely term the “homeless people” at Scotty’s. They don’t know the half of it.

Everyone has their own story

MWM managed to speak with a few of them, like the single mother with four kids on the autistic spectrum. “I’ve been bouncing between motels and public parks across Adelaide for months. (Other tenants) can’t stand the noise my kids make, so they just kicked us out again,” she said, as she packed her bags for another night sleeping rough.

Then there’s the ex-crim with mental health issues, recently released into EA from institutional care. “They won’t tell me how long I’m allowed to stay here,” he told MWM, before he disappeared from Scotty’s, his fate shrouded in secrecy.

Two squatters bravely pitch a tent in the dog park across from Scotty’s, dodging council workers under instructions to move them on. They’re on Housing SA (SAHT’s) Category 1 waiting list, the pair told us, but may still have to wait a year,

it’s winter, it’s cold, and we’re sleeping in a tent in a dog park where drug deals go on.

Ignored by society and bureaucracy alike, the homeless in EA rely on housing agencies whose flowery mission statements are light years away from a reality of maintenance backlogs, rancid customer service, lengthening wait lists and a regime of secrecy straight out of post-war East Berlin.

My story

Our fourth and final case study is me. That’s right, your humble scribe, a graduate and journalist, fell on hard times after a mid-life crisis and a flurry of self-sabotage left me with nothing but modest SAHT digs.

I was recently diagnosed with ADHD, which finally explains a bunch of traits (including my prickliness). I upset SAHT in 2017 by getting a court order against a drug associate neighbour and forcing them to move him out. A few months later, SAHT replaced one ‘colourful’ next-door tenant with … another one (and a succession of live-in associates).

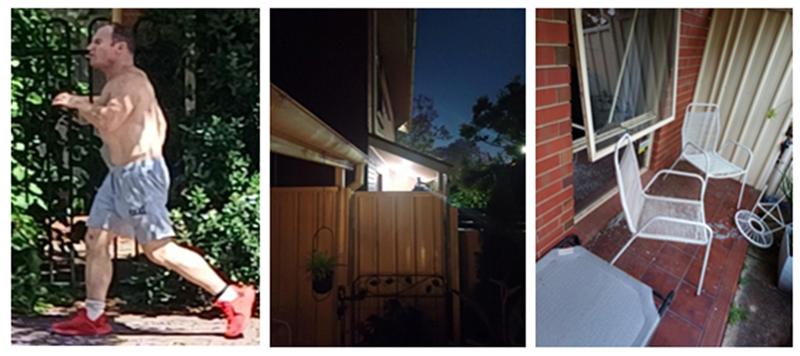

Image supplied

A six-year nightmare ensued, the last (and worst) 18 months of which saw this character (above left), living metres away. Resembling an extra from the TV series Underbelly, he currently reports to Community Corrections following one legal entanglement or another.

Also pictured (centre) is my neighbour’s porch light, which stays on 24/7 for some reason, and the damage done to my home during one of multiple attempted burglaries. Was placing this nightmare next to me a mistake on SAHT’s part, or had I upset the wrong staff member by having them move the previous guy out?

Six years of fear, fights, fishy foot traffic and flat tyres with screwdriver-sized holes later, I’d had enough. Another Court order and letters to the Housing Minister spawned an agreement to place me in EA at Scotty’s while SAHT moved these miscreants on.

It would take “a month or so” before I could move back in, they said. I’m into my sixth month here at Scotty’s.

Endless waiting and secrecy

A near-universal gripe among public housing tenants and those of us in EA is the service delivery, which wouldn’t cut it in the Third World. Make a request and you might get an answer by next March; lodge a complaint and you could still be waiting come the Rapture.

I can just about count on one hand the number of times a call, email or request has been satisfactorily answered. “There are far fewer (housing officers) per tenant in public housing than in non-government social housing”, NSW Tenants Union CEO Leo Patterson Ross told MWM.

Image supplied

If you’re silly enough to ask why they’re taking so long to fix your sagging ceiling, or how you wound up with a neighbour like mine, chances are you’ll hit a brick wall of secrecy. For example, earlier this month I was denied documents under Freedom of Information (FoI) which might tell me why they moved my problem neighbours in (and who did it) despite their knowing I can’t cope with people like that.

What reason did they give for denying me the documents? Because SAHT thinks it might “have a substantial adverse effect” on them (no kidding. Bringing SAHT staff to account for egregious conduct is not “adverse”; it’s in the public interest).

Experts we contacted confirm the obvious: agencies like SAHT are secretive because they’ve got stuff to hide, be it corner-cutting on basic services or stuff-ups due to a lack of quality staff. “Public housing agencies have obligations to perform at a certain level, and budgets that make it impossible to get there,” one tenants’ advocate said.

As for me, I’ve been kept in the dark, fed misinformation and strung along (“just a few weeks longer and you’ll be back home”) since February, and I’m not the only one to experience this. Being a part of such duplicity must be soul-destroying for those SAHT staff who still care.

Public housing sell-off

Following two decades in which more than 20,000 public homes were sold off to private buyers, SA’s first term Labor government moved to turn that around in 2022. Budgeting $232.7 million for 564 new homes through next year, the state also pledged “upgrades to existing homes”, so run-down properties like the ones pictured (above) don’t go unused.

But that’s just a drop in the ocean that is SA’s public housing waiting list. The queue has barely shrunk, from 17,000 when Labor took office to an estimated 16,000 now. Meanwhile, repairs and renovations at empty properties can take years, in a state where there are four times more vacant public homes (mine included) than rough sleepers.

However, the problem extends beyond demand and supply, as one SAHT source informed me early this year, “I was brought in to make changes (at SAHT’s Adelaide office) but it’s an uphill battle,

with lack of money, the culture here and the turnover of unhappy staff.

The source who told me of these problems, an acting manager, wanted to change the system from within. But those best-laid plans seem to have been squashed following the return from leave of the permanent manager at Adelaide office, someone seemingly unfazed by such sins as secrecy and third-world service delivery.

No remedy in sight

Within weeks of this manager’s return to duties, she’d failed to return a growing pile of emails, cut off access to SAHT services after I complained about it (angrily, I’ll admit, but with cause) and banned staff from confirming or denying there was even a process – agreed to in February – of moving my neighbour on.

But the worst of it was this unsigned email, sent late one Friday afternoon, ending my EA despite the ongoing threat my neighbour (who’s still there) and his associates pose to me. The timing of this email gave me hours to somehow get it reversed (I did, thanks to advocates of mine), but it could have seen me forced to live out of my car for fear of going back there.

Was the manager acting in good faith on wrong-headed advice from police who’d never spoken with me or taken a serious look at the umpteen incidents I’d reported, or did she actively seek that advice after one too many complaints on my part?

“When they get called out for failing on their customer service obligations, they attack the messenger, not the problem,” one tenants’ advocate said.

Whose ‘fault’ is it anyway?

Why is there a lack of money for new public housing, quality staff and the “wrap-around” support you find in places like Scandinavia?

ACOSS CEO Cassandra Gold points to the notion – embedded in our culture – that poverty is “the victim’s fault, not society’s”. Victim–blaming is a tradition in Australia, leading to a lack of political will to house and care for the poor.

It’s an attitude that flows through to bureaucracies and backbenchers alike, as I discovered when they tried to end my EA. This was the darkest moment of my ordeal, a period during which, I’m ashamed to admit, I self-harmed.

Tearful, emotional pleas for help from my local MP, Cressida O’Hanlon, led to a response of, “Given the nature of recent communications … Cressida’s office is (unable) to provide further assistance.” I was not abusive, and the cause of my distress was completely ignored.

People in crisis can often present as upset and, yes, angry. This may come as news to bureaucrats and politicians, many of them predisposed to victim-blaming and seemingly,

unable to understand that their indifference has human consequences.

Meanwhile, the waiting list for public housing alone (Australia-wide) is an appalling 169,000. Even people on the priority list (Category 1 in SA) can be waiting what seems like forever, their lives effectively on hold. I’ve met many people transitioning in EA at Scotty’s, and I have nothing but sympathy for their plight, “screams and scuffles” notwithstanding.

Most are much worse off than I am, and many won’t be resourceful (or connected) enough to thwart the bureaucrats (as I did) if they suddenly cut EA off. I also have the rare ability to write about this ordeal, although SAHT seems not to have taken my promises to do so seriously.

MWM contacted SAHT, Minister Champion and Cressida O’Hanlon MP for comment, but had not heard back by publication time.

Three decades of policy failure. Productivity Commission’s housing shame file

An Adelaide-based graduate in Media Studies, with a Masters in Social Policy, I was an editor who covered current affairs, local government and sports for various publications before deciding on a change-of-vocation in 2002.