Is it ethical to promote the health benefits of “low GI” labelling? How about multinational food companies paying to have their products certified? At best, it provides little value to the consumer, writes science journalist Dr Maryanne Demasi, At worst, the low GI symbol is misleading and should pass the way of the Heart Foundation tick.

FOR DECADES, “low GI” foods have received the backing of high profile scientists and nutritionists, promoting them as the “healthier choice”.

A lucrative industry has evolved whereby food companies pay to showcase the low GI symbol on the front of product packaging, much like the now defunct Heart Foundation tick.

A lucrative industry has evolved whereby food companies pay to showcase the low GI symbol on the front of product packaging, much like the now defunct Heart Foundation tick.

Recipe books, weight loss programs and nutrition health messages are often bound to the notion that low GI foods are “better for you”. But a closer examination of the science exposes fundamental flaws that threaten the credibility of the low GI industry. What is low GI and are consumers being misled?

What is Low GI?

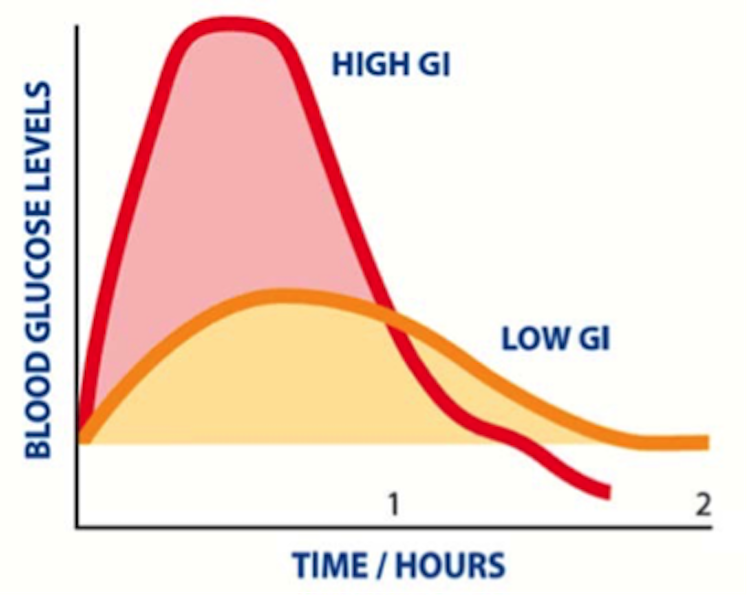

According to the Glycaemic Index (GI) Foundation, the “GI” of food is simply a ranking of how quickly various foods cause a spike in your blood sugar levels.

The entire concept was based on the results of only 10 healthy subjects who ingested carbohydrate-laden foods and the effect on their blood sugar levels was assessed.

The GI scale ranges from zero to 100. A GI of ≤55 is classified as “low GI” because it causes a slower rise in blood glucose compared to “high GI” (see graph)

Does GI work in practice?

On the surface, the GI concept makes sense.

That is, the low GI symbol should guide consumers to choose products that will not spike their blood sugar levels too high, which is especially important for people with diabetes.

Except, the science doesn’t back it up.

Researchers have put it to the test and determined that the GI of food cannot predict, with any accuracy or precision, the way a person’s blood glucose will respond.

For example, when 63 healthy subjects ingested an identical meal of white bread in order to calculate its GI (based on the protocol), the results were highly variable. The range of individual responses to white bread saw GI calculations as low as 35 whereas others were as high as 103.

With such a large margin of error, the researchers concluded that there was “substantial variability in individual responses to GI, demonstrating that it is unlikely to be a good approach to guiding food choices.”

Registered nutritionist Anthony Power says these results demonstrate the futility of labeling products with the low GI symbol.

“The method for ranking the GI of food might work well in a test-tube but it does not translate to the human body,” says Power. “The variability in people’s response to GI does not make the tool useful”.

Prof Eugene Fine, a physician from at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY says “the whole point of the GI, is supposed to be its usefulness in predicting blood sugar levels. But since studies show such a broad scatter plot, it’s clinically useless”.

Prof Mary Gannon, nutrition researcher from the University of Minnesota, agrees.

“In our opinion, the clinical relevance is minimal. The reliability of the GI as a standardized index of food response is questionable,” says Gannon.

Another fundamental flaw in the GI labeling of food is that various situations will alter the GI properties of food once its ingested.

For example, the GI of a slice of bread will change if it is accompanied with butter or avocado, rendering the GI label redundant.

In defence of GI

Professor Jennie Brand-Miller, nutrition researcher and early pioneer of the GI concept, has defended the criticisms, although she does concede that low GI foods have variable results in people.

“It’s been known for a long time that glycaemic responses are highly variable between, and within, individuals,” says Brand-Miller in a written response. “But the Glycaemic Index is a property of the food – not the person – determined by testing 10 people according to a precise protocol of over 300 data points”.

Prof Brand-Miller adds, “The GI ranks foods according to their glycemic potential, gram-for-gram of carbohydrate.”

However, Richard Feinman, professor of biochemistry and medical researcher from SUNY Downstate Medical Center NY, says there’s no point assigning an index to food, if it doesn’t have any relevance in the human body.

“The studies demonstrate that there is no ‘true’ GI for any food that reliably predicts a person’s blood glucose,” says Feinman.

Prof Brand-Miller, who promotes the benefits of low GI foods, did disclose that she receives royalties from co-authoring low GI books along with other high profile nutritionists.

According to the University of Sydney, Prof Brand-Miller’s book sales “have gained her international acclaim, having sold over 3.5 million copies since 1996”.

GI for people with diabetes

Originally, the GI label was intended as a tool for meal planning for people with diabetes. Prof Brand-Miller says low GI diets have been shown to reduce blood glucose levels in people with diabetes.

“A large body of research shows that diets based on healthy low GI choices improve glycemic control in people with diabetes, and reduce the risk of developing diabetes in healthy populations,” says Brand-Miller.

However, Associate Professor Kieron Rooney, exercise and obesity researcher from the University of Sydney suggests that the GI ranking of food is likely to have very different outcomes in people with diabetes.

“It is possible that most products would be high GI for a person with diabetes by nature of the underlying disease,” says Rooney referring to the inability of people with diabetes to naturally control blood sugar levels.

Even if low GI food reduces the spike in blood sugar, the total “load” of glucose entering the blood stream still has to be processed, which requires substantial amounts of the hormone insulin. Symptoms from high insulin levels include food cravings, fatigue and weight gain.

Prof Gannon suggests a more practical alternative to focusing on the low GI diet. “A more clinically relevant approach for dietary treatment of high blood sugar would be to limit dietary glucose,” says Gannon.

Put simply, people should eat less starchy carbohydrates, which get converted into glucose once ingested.

Professor Feinman agrees. His recent study demonstrated that restricting dietary carbohydrates should be the first approach to managing diabetes, over the low GI diet.

In addition, Professor Eric Westman and colleagues at Duke University Medical Centre NC, conducted a study in people with type-2 diabetes and showed that restricting dietary carbs led to greater improvements in blood sugar control and reduction/elimination of medications, compared to the low GI diet.

A marketing ruse?

GI is focused on “glucose” and overlooks other sugars like fructose, which is often added to sweeten foods in the form of refined cane sugar, corn syrup or fruit concentrates.

“The standard methodology for assessing GI is to utilise a glucose drink as the reference food,” says Rooney, “but the most common sugars added to products will contain significant levels of fructose. Therefore, if one is only measuring blood glucose response to a food you are missing out on a lot of the story.”

Fructose has a low GI (doesn’t spike blood glucose levels). Therefore, food manufacturers have been able to exploit this loophole.

Products can be sweetened with concentrates containing fructose and rewarded with a low GI symbol, essentially giving a “healthy halo” to highly processed sugary foods.

For example, low GI foods include Golden North Good ‘n Creamy Vanilla ice cream GI = 31, Sanitarium™ Up & Go™ Chocolate drink GI = 28 or Nestlé® Milo® Energy Dairy Snack GI = 45.

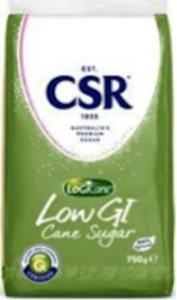

Even pure table sugar is marketed with the low GI symbol, CSR LoGICaneTM, claiming that it’s a “healthier” sugar.

“I am not convinced that by consuming a lower GI form of another refined sugar product, the health of an individual will be improved,” says Rooney.

“We need to shift away from a culture of adding refined sugars and seek enhancing the palatability of our diets by consumption of natural unrefined/minimally processed foods,” says Rooney. “In any policy that hopes to inform people on foods and drinks to maintain or improve glycaemic control, I think fructose has to be considered.”

Chronically high levels of fructose have been associated with fatty liver disease and diabetes.

When asked whether fructose sweetened drinks like Sanitarium™ Up & Go™ Chocolate drink were considered “healthy” because of their low GI symbols, Prof Brand Miller declined to comment.

“Just because a product is low GI, it does not mean it hasn’t got a sting in its tail,” says Power. “As a practitioner who counsels patients to reduce their sugar, sweetener and carbohydrate intake, I find products like Low GI sugar to be unhelpful, misleading and possibly harmful to patients. It should not be allowed.”

Who supports GI?

Despite Prof Brand-Miller’s defence of GI, official guidelines do not endorse low GI diets.

For example, Health Canada has stated that “the inclusion of the GI value on the label of eligible food products would be misleading and would not add value to nutrition labelling and dietary guidelines in assisting consumers to make healthier food choices.”

In response to the question of whether low GI foods are healthier, UK’s National Health Service (NHS) states

“using the glycaemic index to decide whether foods or combinations of foods are healthy can be misleading”.

Closer to home, our National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) dietary guideline’s committee, also does not officially endorse the low GI diet. And despite the GI Foundation lobbying the NHMRC to change its mind, the response was a direct one;

“The Committee agreed that there was insufficient significant evidence to support change. It was noted that this is a physiologically based classification, with large variability and several limitations.”

Meanwhile, the GI Foundation, the University of Sydney and its high profile advocates continue to profit from the marketing of low GI foods.

Will the “Low GI symbol” suffer the same fate as the “Heart Foundation Tick” which was scrapped after consumers complained it was “health washing” highly processed, sugary foods?

What remains now, is a question of ethics.

Is it ethical to promote the health benefits of low GI labelling? At best, it provides little value to the consumer. At worst, it misleads them.

——————–

Dr Maryanne Demasi

Dr Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in Rheumatology.

You can read more about Dr Demasi’s work on her blog, or follow her on Twitter @MaryanneDemasi.

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

Dr Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in Rheumatology. She has done a number of important stories for michaelwest.com.au including investigations into the infiltration of the medical profession by processed food companies and the over-prescription of statins.