Labor and the Coalition look like reaching historically low joint levels of support at the election. The assumption is that this will result in a hung parliament. But there is another scenario, a super long-shot which belongs at the very outer edges of the possible. Mark Sawyer imagines a deal like no other but a deal, potentially, with limitless money behind it.

The election has so many variables. Majority government for Labor (and less, likely Coalition). Hung parliament with Teals in charge. Hung parliament with Greens in charge.

Or something completely kooky: a grand coalition.

In other words, Labor and the Coalition cutting a deal to deliver stable government for the life of the parliament. A rotating prime ministership. An agreement to dissolve the partnership at the next election and fight as separate parties again.

Crazy? Yes. Bloody unlikely? Yes. But impossible? No.

Impossible, once, was war in Europe in 2022, or a virus flattening everything in its sight and closing down society (and now, our society becoming inured to the continuing casualty tallies). There’s a long list of impossibles. Trump. Brexit. Same-sex marriage. Defeat for the republic referendum. Scott Morrison winning in 2019.

Conventional wisdom is that the high expected vote for minor parties and independents will result in a hung parliament and force either the Coalition or Labor to the negotiating table. But there is an alternative: the Coalition and Labor, governing together to ‘’save the nation’s energy security’’.

Fossil lobby’s dream option

Energy policy is the only issue which might bring the majors together, but it’s a massive issue. And, as has been reported in MWM, Labor is closer to the Coalition on energy policy, and the matter of new fossil fuel projects, than it is to the Greens and the climate independents.

To the chagrin of the Greens and independents, there are 114 new coal and gas projects in the pipeline in Australia. Although both climate progressives and international energy authorities want a ban on new fossil fuel projects, fossil fuel corporations are huge donors to the Coalition and Labor. Their lobbyists are pervasive in Australian politics, state and federal, and are significant donors themselves.

Even in recent days of the campaign, Labor quietly edged closer to the Coalition on emissions reduction exemptions. This was to woo voters in coal seats but the corporate money is where the real pressure lies. Coal, oil and gas prices have shot through the roof in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Already,

ExxonMobil Australia filed its 2021 financial accounts over the weekend which showed revenue had jumped by more than $2bn last year to more than $12bn; and that only captures a part of the recent price surge. These fossil fuel giants are now making extreme profits, profits which will be directed towards buying as much political influence – and locking down as much future production – as possible.

State versus state, gas mate versus gas mate, a fossil fuels bonanza with a planet on the line

And it speaks to this political influence that despite the profits bonanza and despite fossil fuels multinationals being, as a sector, perhaps the most egregious tax avoiders in Australia, that they receive some $12bn a year in public subsidies.

That’s the money. As for emissions, emission reduction targets for 2030 don’t seem to leave much room for negotiation except by Labor and the Coalition.

The Greens are aiming to reduce emissions by 75% and the independents are likely to go for 60%. Meanwhile the Coalition pitches 35% and Labor 43%. With power prices skyrocketing in the eastern states, the demands of the Greens and the independents might look like a bridge too far in the event of a hung parliament. That’s before we consider the repercussions for energy security from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Who can claim a mandate?

The polls give Labor and the Coalition about a third of the vote each, leaving the remaining third to be divvied up by the Greens, independents, One Nation, Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party, and a host of others.

A party claiming 35% of the primary vote could hardly claim a mandate to govern. Even Labor and the Greens (as a coalition of sympathy if not fact) are not likely to top 45%.

The House of Representatives has 151 seats. There could be as many as 15, even 25 at a stretch, cross-benchers in the next parliament.

The independents hold Warringah (NSW), Indi (Victoria), Mayo (South Australia) and Clark (Tasmania). The Greens hold Melbourne (Victoria). Liberal turncoat Craig Kelly holds Hughes (NSW) for the United Australia Party and Bob Katter runs his own show in Kennedy (Queensland).

Kelly’s position is hopeless. So, assuming the rest hold on, that leaves 145 seats. Which ones are vulnerable to moving out of the major-party column?

Independents rising

The independents are strong in North Sydney and Wentworth (NSW), Goldstein and Kooyong (Victoria), Curtin (Western Australia) and Mayo (SA). Mackellar, Bradfield, Reid, Hughes (NSW) and Nicholls (Victoria) can’t be ruled out either.

The Greens have hopes for Higgins (Victoria) and the Queensland seats of Griffith, Brisbane and Ryan, where the movement of climate independents is not so well established as in other states (wait for 2025). There’s a faint chance of the Greens pulling upsets in Richmond (NSW), Macnamara (Victoria) and Canberra (ACT). And there’s some long shots: Kooyong (Victoria), Grayndler and Sydney (NSW), the latter two only after Anthony Albanese and Tanya Plibersek retire.

In the event all these seats (barring Grayndler and Sydney) were lost by the major parties, the Coalition and Labor would have 127 seats (we didn’t count Higgins and Hughes twice). Realistically, assuming the major parties can ”sandbag” (throw big resources at) some seats, there might be 130 to 135. The number of either bloc is subject to variation because the major parties are likely to take seats off each other. But one thing is sure in that scenario: no party would muster the required 76 seats to govern in its own right.

The negotiations would begin quickly, but might break down just as fast.

Greens and Labor, a rocky relationship

Let’s assume Labor gets first throw. The first thing Anthony Albanese might do is tell the Greens there are no deals to be done. The Greens would hardly flee into the arms of the Liberal and National parties.

Hellbent on banishing the Coalition government, the Greens don’t have much of a negotiating fallback. Apart from stopping the government from opening new coal mines and gas plants, their wish list includes dental care on Medicare and the waiving of student debt. And the beautiful dream of big corporations and billionaires paying their fair share of tax.

No problem, Labor might say to the non-climate stuff. But the ALP is still feeling burnt by the minority government of 2010 to 2013, which it believes gave too much power to the Greens. It might just present the Greens with a take-it-or-leave-it deal. As one Labor backroom operator foreshadowed a possible Labor taunt to the Greens if they hold out against Labor: ‘’Go back to your branches and tell them you are supporting Scott Morrison and Barnaby Joyce.’’

Then there’s the climate independents, the Voices Of, the Teal Brigade, call them what you will.

These independents have emphasised an integrity commission. That won’t be a problem for Labor. Even the Coalition would patch together something to save its skin.

But, denuded of some of its leading lights (Josh Frydenberg) and leading moderates (Dave Sharma, Tim Wilson, Trent Zimmerman), the Coalition under Peter Dutton or even a continuing Scott Morrison might prefer to take its chances in opposition, rebuilding by marching (even further) to the right.

On Monday news emerged that Morrison has written to religious bodies promising renewed push for a religious freedom bill, with no added protections for the LGBTQI+ community.

Save the coal and gas!

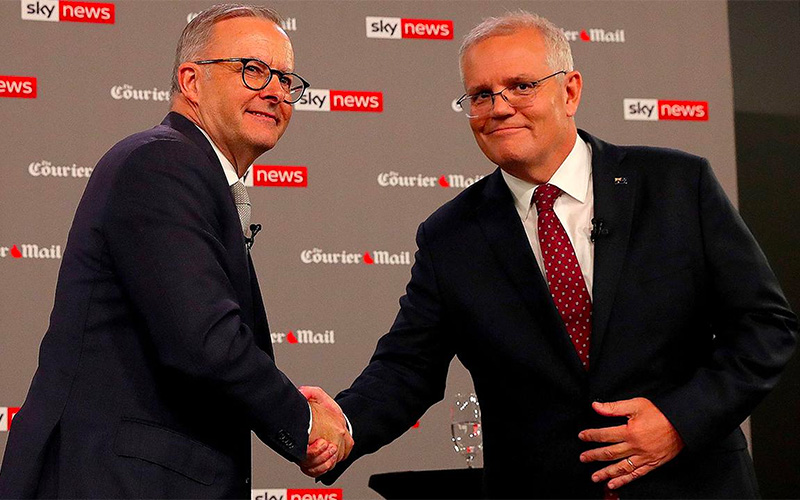

Which brings us to the weirdest thing Australia might see in an already weird decade: the unholy alliance. But an unholy alliance presented as a salvation to the nation. Imagine Morrison and Albanese going to the Governor-General with a plan for an ‘’orderly transition’’ to clean energy that keeps the lights on (it would certainly please their fossil fuel donors).

They would pledge to contest the 2025 election as separate entities again. A ministry would be constituted with clear boundaries. The Coalition, say, would get Treasury and Defence. Labor: Health and Housing. It would be quite amicable. Emissions policy would converge at something between a 35% and 43% cut, and the existing fossil fuel export base, plus those 114 coal and gas projects, would be safe.

A long long-shot

Yes, it’s the longest of long shots. Much of this article will read like science fiction. But don’t underestimate the desire of the big parties to keep the Coles-Pepsi duopoly; and the big money behind them. Even Margaret Thatcher expressed relief after dealing out one election thrashing to Labour that her foes had survived as the official opposition instead of a third force.

On Monday, Greens leader Adam Bandt said the Australian people don’t want a second election. And the Teal independent in Kooyong delivered an ultimatum.

‘’The major parties will just have to come to the table if they want to form a government if there’s a hung parliament,’’ Monique Ryan told ABC radio. ‘’They’ll have to be pragmatic, they’ll have to negotiate.’’

Both Bandt and Ryan might see the rug swept from underneath their feet. And the ‘’pragmatic’’ side of these negotiations might surprise us all.

We’re through the looking glass, people.

Wake in fright. What another election loss would do to Labor

Mark Sawyer is a journalist with extensive experience in print and digital media in Sydney, Melbourne and rural Australia.