The drop in skilled workers arriving in Australia has hit the economy, and it began six years before the Pandemic. Alan Austin reports on the decline of innovation and the jobs crisis.

If you can’t find a hydrogeologist, sonographer or hairdresser when you need one, this is probably why. Data from the Department of Home Affairs confirms Australia’s historically successful program of welcoming migrants with specialised qualifications is being systematically dismantled.

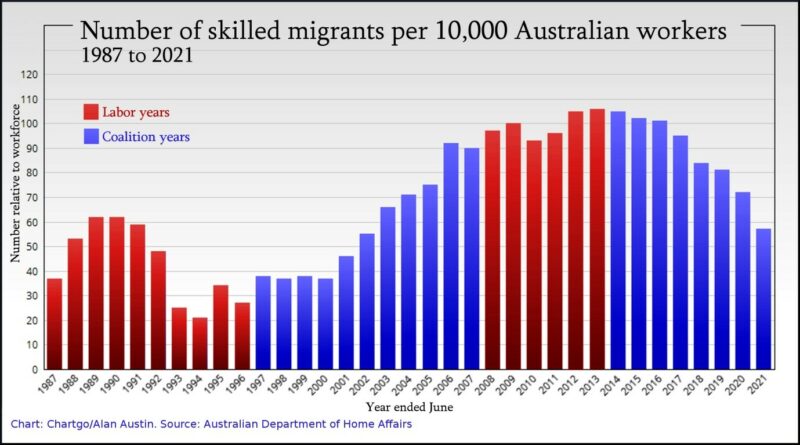

From a peak in 2013 of 106 skilled migrants for every 10,000 Australian workers, this ratio has declined every year. It was cut drastically in 2018 from 95 to 84, then fell sharply in 2020 from 81 to 72. It tumbled last year to just 57, almost half the 2013 zenith. That was the lowest rate since 2002, when the Howard-Costello government was rapidly expanding the program – and reaping significant economic benefits.

The chart below is based on data from Australian Migration Statistics 2020, updated with the latest edition of The Administration of the Immigration and Citizenship Programs. The shape of the graph from 2013 onwards shows this cannot be blamed on the pandemic.

Impact on the economy

There is little doubt the collapse in skilled worker arrivals has been one contributor to the overall demise of Australia’s economy since 2014. One of several. The ever-diminishing availability of qualified technical staff has directly impacted innovation, scientific and medical research, manufacturing output and the ability of many enterprises to function efficiently. These have contributed in turn to lower productivity, slower economic growth, stagnant wages and reduced company profits in some sectors, although these have generally been robust. Thus overall standards of living have almost certainly been reduced significantly, even if quantifying by how much is a challenge.

The actual numbers are substantial. Or they were. In its first full financial year, to June 1997, the Howard government increased the intake from 24,100 to 34,676. It stayed around that number until 2000 when rapid expansion commenced. From 44,721 in 2001 experts arriving jumped to 66,053 in 2003, then to 77,878 in 2005. At 97,336 in 2006 the intake under Howard had quadrupled in 10 years.

Under Rudd and Gillard, the expansion continued, despite a dip in 2010 during the global financial crisis. The peak intake in 2013 was 128,873.

Global innovation ranking

From ranking 22nd in the world on the Global Innovation Index in 2009, Australia rose to 18th in 2010 and up to 17th in 2014. A steady slide began soon thereafter. From 19th in 2016, Australia slipped to 20th in 2018, to 22nd in 2019, then 23rd in 2020 and down to the lowest ranking on record last year at 25th.

Other global agencies have tracked similar declines. The World Economic Forum measures “technological readiness” for 141 nations. Australia’s ranking fell from 19th in 2013 to 21st in 2016 and down to 27th in 2018.

Slower growth in gross domestic product (GDP)

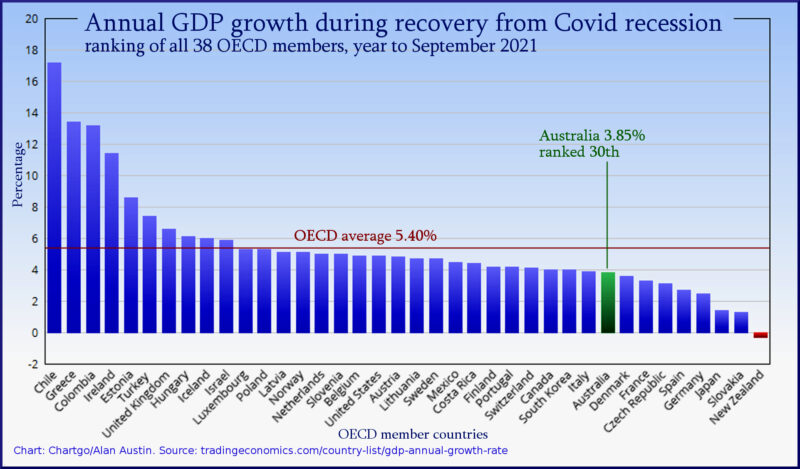

The decline in economic growth rankings over the Coalition’s tenure is easier to demonstrate. When skilled migration was near its peak, Australia enjoyed one of the strongest annual GDP growth rates among the 38 developed OECD member countries. In 2009, its annual GDP growth was the OECD’s highest.

Currently, in contrast, Australia’s annual growth ranks 30th in the developed world, the lowest level on record. Australia’s modest 3.85 per cent growth for the September quarter, the latest data, is well below the 5.40 per cent OECD average. See blue chart, below.

Australia’s quarterly rate of GDP growth for the September quarter was an appalling negative 1.9 per cent, the third lowest on record. (The lowest was negative 6.8 per cent in the June quarter 2020.) Australia’s OECD ranking on quarterly growth in the September quarter was a dismal 36th out of 38. Only Iceland and New Zealand were lower.

The architect of the decline

Scott Morrison appears to be the key cabinet decision-maker in this substantial shift in policy – which began on a substantial scale in 1985 under Bob Hawke. Morrison was immigration minister in 2013 and 2014, then treasurer from 2015 to 2018 and has been prime minister since 2018.

Skills in demand

Cutting back migration may not have been a great problem had education and training been ramped up to meet the demand for trained staff. Clearly, this has not happened.

Expertise lacking in Australia is listed in a schedule published by the National Skills Commission. The latest priority list shows 57 occupations currently in national shortage with strong future demand. These include specialists such as aircraft structural maintenance technicians, sonographers and geotechnical engineers. It also includes welders, bakers, chefs and nurses, which Australia should be able to recruit from among the 245,000 jobless youth.

Nine occupations in shortage have soft future demand, including farmers, grape growers and roof tilers.

The schedule lists 87 occupations in short supply with moderate future demand. These include floor tilers, greenkeepers, personal carers and dental assistants, which do not appear to require lengthy specialist training. It also includes hydrogeologists, geophysicists, cardiologists and diversional therapists which probably do.

Perhaps we all need more diversional therapists.

Alan Austin is a freelance journalist with interests in news media, religious affairs and economic and social issues.