The first report since the Safeguard Mechanism demonstrates the fundamental flaws in a system that may reduce emissions overall, but is certain to increase the profits of some emitters. Kim Wingerei reports.

The Clean Energy Regulator’s report on Australia’s biggest polluters covers the 2023-24 financial year, and shows that emissions had dropped by approx. 2% from the previous year, and were 0.6% better than the baseline (as explained below). According to climate change analyst David McEwen, the total profit to those who reduced their emissions was $280m based on the $33 per tonne current trading price of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs).

The Safeguard Mechanism (SGM) covers 217 industrial facilities whose carbon emissions exceed 100,000 tonnes annually. Each facility must reduce its emissions every year until 2030, from a baseline which is lowered by 4.9% every year, except for the so-called “trade-exposed facilities” such as steelworks, aluminium smelters and paper mills, their baseline lowered by 1%.

Facilities that reduce their emissions by more than the baseline accumulate Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs), which can either be banked to offset future failures to meet the baseline target or sold to other emitters who may need them to offset their own emission reduction failures.

It’s a mechanism similar to how ACCUs work (or don’t), and akin to the principles of the Catholic Church confessional to save the souls of sinners.

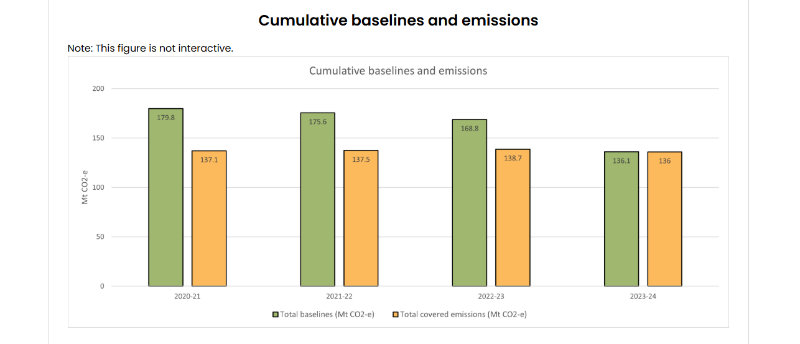

In the first year of the reformed Safeguard Mechanism, facility baselines were reset. This resulted in aggregate headroom being almost completely removed. Aggregate headroom is the difference between total covered emissions and total baselines.. Source: cer.gov.au

At first blush, the scheme appears to have delivered genuine emissions reduction and overachievement against the new baselines.

However, McEwen says, “One year is little time to implement genuine emissions reductions, and most changes in reported gross emissions (before carbon credit adjustments) likely relate to production variations or reporting inconsistencies.”

He also points to a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) stating that the “adoption of an alternative method for calculating fugitive methane emissions gave many coal mines lower reported emissions without lifting a finger.”

Sins of emission

The aggregate numbers don’t tell the whole story, as half of the 33 largest polluters (those emitting more than 1 million tonnes) declared higher emissions than the previous year. These facilities represent 80 mega-tonnes or about 60% of emissions covered by the SGM, including the top two, Chevron’s Gorgon and Inpex’s Ichthys gas extraction and LNG processing plants.

Gorgon is responsible for around 2% of Australia’s total emissions – so much for its famed carbon capture and storage (CCS) plant – and its emissions were up 7.5% or 610,000 tonnes.

Icthys is responsible for about 1.5% of Australia’s emissions, and its emissions grew at twice the rate of Gorgon’s: 14.7% or 860.000 tonnes. And as McEwen points out, “these are solely emissions created at the facility: when the gas reaches its export destination and is burnt, those consumption emissions are an order of magnitude higher.”

Konnichiwa! The Japanese are not so keen on our gas. What’s the scam?

Overall, 147 facilities reported emissions above their baselines (two others miraculously reported actual emissions exactly as per their baseline).

Woodside’s North West Shelf project led the under-performers on a tonnage basis, coming in 608,000 tonnes above its baseline, despite its reported emissions falling. Second was Queensland Alumina at 324,000 tonnes over its baseline. The next 12 facilities in the sinners league table are all coal mines, coming in a collective 2.5 million tonnes over baseline.

Six companies reported emissions that were over double their baselines: four coal mines, Santos’ Darwin LNG plant, and BHP’s NMK01 Nickel West facility.

All up, the under-performers were nearly 9.1 million tonnes above their baselines. This resulted in 7.1 million tonnes worth of Australian Carbon Credit Units being “surrendered” (i.e. used as an offset) and a further 1.4 million tonnes of newly minted Safeguard Mechanism Credits being presumably bought from over performers and surrendered. The balance was carried forward.

Sinners are winners

The largest claimed fall in reported emissions year on year was from the third highest emitting Safeguard facility: Woodside’s North West Shelf, which fell 12% or 840,000 tonnes (apparently due to reduced production), and Anglo Coal’s Moranbah North Mine, reportedly down a whopping 35% or 790,000 tonnes (again due to reduced production, plus claimed improvements in methane management).

In total, 68 facilities recorded gross emissions below their baselines, an over-performance summing to just under 9 million tonnes. Of these variations, the largest beneficiaries were Shell’s Floating LNG gas site in WA and Anglo’s Capcoal coal mine in QLD, each recording actual emissions over one million tonnes below their baselines.

This is a significant claimed over-performance of the industry average. FLNG’s reported emissions were under 1.9 million tonnes, 37% lower than their baseline of over 2.9 million tonnes. Capcoal’s was an even more impressive 49% lower!

Other winners were coal mines Anglo Grosvenor, Adani Carmichael, Endeavour Appin and Tahmoor Coal. Mount Bruce’s Gudai-Darri iron ore mine (operated by Rio Tinto) and Orica’s Kooragang Island ammonia plant rounded out the top ten winners (by tonnage).

The Gudai-Darri iron ore mine won the prize for the largest variance below its baseline, with its reported emissions of 130,000 tonnes, a whopping 79% below its baseline of 604,000 tonnes.

Collectively, the over-performers were permitted to issue nearly 8.3 million SMCs.

Is the SGM working? It’s complicated

David McEwen asks, “Is the Safeguard Mechanism working? Will it deliver genuine industrial emissions reductions as opposed to benefiting carbon credit markets? Will it stunt future mining or industrial investment, or send existing facilities to the wall?”

He contends it’s too early to establish any trends, but every year, as the baseline number drops by 4.9%, it will become harder for emitters, which will likely mean higher prices for carbon credits, and higher profits for those who do manage to reduce their emissions.

There is, however, an annually adjusted cap of $75 per ACCU/SMC. Under the Safeguard amendments negotiated by the cross-bench, all new facilities must meet or exceed best practice benchmarks, and new LNG (export) projects must achieve zero emissions of carbon dioxide mixed in with the methane gas that is being extracted. New shale gas projects are supposed to receive a baseline of zero.

“Given recent project approvals, we will see how this is applied in the years to come.”

As Michael Corleone found out, despite seeking absolution from the Pope, in the end, the price of his sins was too much to bear.

Another day, another gas approval as Labor caves on big dirty Barossa

Kim Wingerei is a businessman turned writer and commentator. He is passionate about free speech, human rights, democracy and the politics of change. Originally from Norway, Kim has lived in Australia for 30 years. Author of ‘Why Democracy is Broken – A Blueprint for Change’.