Are retirement villages a rip-off? Retirees could be up to a million dollars worse off if they moved into a retirement village than if they remained at home, according to new analysis. Callum Foote reports.

Data on the number of Australians living in retirement villages are hard to find. However, according to a 2014 report produced for the Property Council of Australia, by 2025 some 7.5% of over 65’s will be living in retirement villages. This equates to an estimated 382,000 more Australians in retirement villages in just a few years.

The lobby group’s 2020 retirement village census shows the average age of retirement village residents is 81 years, and their average residency being for 8-9 years. These figures have grown in recent years.

New research from retirement village analyst Les Scobie shows the dominant financial model for retirement villages, the loan/lease model, is causing a significant transfer of capital from retirees to retirement village operators. In many cases, elderly Australians would be considerably better off if they just stayed at home.

The loan/lease model accounts for 60% of all retirement village tenures nationally and as high as 74% in Victoria with other estimates putting the figure in the realm of 80% nationally.

As per the story linked above, many incoming residents and their families might think they are “buying a unit” in a village when in fact they are making a large, unsecured loan to a property developer at zero interest.

In a loan/lease arrangement, the resident can be offered a 49 or 99-year lease or a life tenure for the payment of an interest-free loan to the operator.

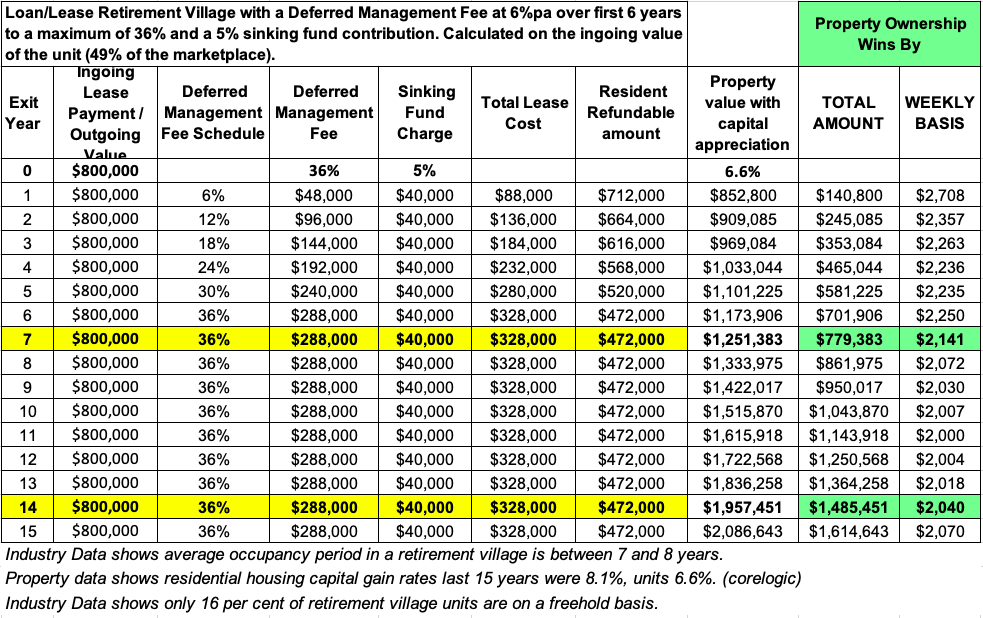

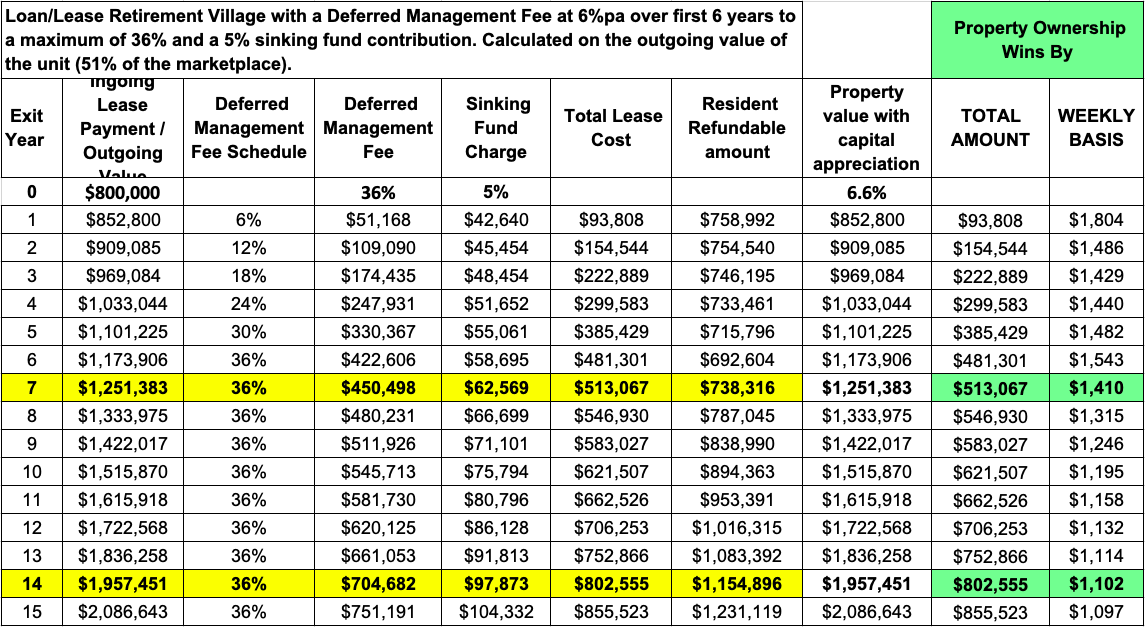

When the resident eventually moves out of the village, the operator returns the loan but takes a “deferred management fee”. According to the Property Council, most DMFs are generally levied at 6 percent per year of the original loan capped at 36%. The operator may also take a sinking fund charge of up to 5% from the loan amount.

At the end of the tenants’ residency in the village, retirees are refunded the loan they gave to the operator, minus the 41% kept by the village operator. Outgoing residents do not get their loan repayment on the day they leave the village, they have to wait until somebody pays to move into their unit or the expiration of a statutory period. This statutory period varies between states but is generally at least 6 months.

No capital gain for half of retirees

According to the Property Council, in half of loan lease deals (51%), the retiree will be given a share of the capital gains made on the unit while they inhabited it, and have the fees taken out of the sales price at the end of their tenure.

In other cases, (49%) the retiree will be locked out of any capital gains and be refunded the original loan amount minus the ‘deferred management fee’ calculated on the ingoing payment plus any exit fees.

Retirees are better off being able to lay claim to a cut of the capital gains; however in these cases, the ‘deferred management fee’ taken by the operator will be calculated on the value that the unit is leased out again for.

The original loan amount is often commensurate with or near to an outright purchase price of a commensurate unit in the general community however, under this model the retiree never obtains ownership.

Calculations by Victorian retirement village advocate and resident Les Scobie, using the most up to date property and retirement village data, show that at the end of the average 8-9 year stay, retirees could be up to $1 million worse off than if they remained in their own home.

Property data from CoreLogic shows that Victorian residential housing capital gain rates over the last 15 years were 8.1% for houses and 6.6% (5.9% nationally) for units.

With these inputs, it is possible to calculate the difference in outcomes from an $800,000 starting position for a retiree, an example price of a retirement village unit.

In the case that a retiree does not get a cut of the capital gains at the end of their residency, the retiree can be up to $950,000 worse off after the end of the medium 9-year stay than if they remained living at home.

Or in other words, the retirement village operators are up to $950,000 to the better than the retirees’ capital.

If the retiree does get a cut of the capital gains, then they are better off. Being just $583,930 down than if they remained at home

All the while, the retirement village operator is able to benefit from the, on average, decade long interest-free loan they are receiving from their village occupants. Grandma and Grandpa have virtually become corporate financiers.

Many may be confused by the loan/lease model, as they really think they are buying the unit.

According to Les Scobie, “The salespeople use terms like buy and purchase when that’s really not what you’re doing.”

This is seen in industry literature aimed at convincing potential retirees to move into villages. The Retirement Village Council, which is a body within the Property Council, 2021 Book of Wise Moves repeatedly makes reference to “buying” retirement village units.

Some examples:

Some want to ‘try before they buy… Some are simply just not in a financial position to buy.”

It is definitely possible to sell a home, buy in a retirement village and retain an amount of cash from the sale…”

Though they do make the declaration that:

“It is important to note that buying into a retirement village is not the same as buying a home anywhere else. In most cases, you don’t purchase the land title to your retirement village unit. Instead, you purchase a right to live in it and use the services and facilities that the village offers.”

Mr Scobie also says, “I don’t think the federal government has realised the dramatically reduced capacity of these retirees on leaving a retirement village to fund their own aged care costs and the subsequent burden on the taxpayer to do so”.

It is worth noting that, in great degree due to their “stapled security” trust structures, the big players in the Australian retirement village sector – Lendlease, Stockland and Mirvac – pay no income tax. Two of these three – Mirvac and Lendlease – also picked up JobKeeper despite their strong financial position.

Callum Foote was a reporter for Michael West Media for four years.