When the Reserve Bank announced the biggest single rise in the cash rate in 22 years, it was not only the end of the era of ultra-low interest rates. Going it alone compared to its international colleagues to quash inflation, Australia’s central bank is gifting banks risk-free billions, reports Callum Foote.

The move by Australia’s central bank to lift its cash rate target by 50 basis points to 0.85% made worldwide news, surprising Australian and international economists alike.

International analysts at Reuters and Bloomberg had been expecting a rate hike of 25 basis points or 40 basis points. This was mirrored by domestic banks ANZ and Westpac who strongly argued for a 40 basis points increase in similar editorials. The domestic swaps market had priced in a 32 basis points move, with the futures market at a more conservative 29 basis points move.

The RBA’s aggressive move was made as “inflation has picked up significantly and by more than expected,” according to the bank’s governor Philip Lowe.

The RBA’s move is out of line with recent rate moves which have been made in tandem with other central banks, traditionally the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve.

The last interest rate rise in Australia was made on May 3, a day before the Bank of England and two days before the Federal Reserve. Of these, the RBA’s raise was the most conservative.

The next opportunity for the Federal Reserve to raise rates if they choose to do so will be on June 14 and 15, with the Bank of England a day after on June 16.

Interestingly, the RBA moved without the normal amount of data that its board usually relies on.

Given the dominance of the US economy, RBA decisions are usually made in that context and US inflation tells us how global interest rates may shift, according to a banking expert speaking to Michael West Media on conditions of anonymity.

How does an interest rate target actually work?

While the interest rate target is just that, a target, the central bank also raises the interest it will pay on money held in its Exchange Settlement Accounts at the same time.

These accounts are what Australian banks use to settle transfers between each other, with the RBA acting as a clearing house. Currently, there is around $400 billion held in these accounts.

The RBA has increased the rate that it pays interest to the banks on the money held in these accounts from 0.25% to 0.75%.

Ex-RBA deputy governor Guy Debelle said publicly before the Senate that the amount payable on these accounts was effectively the risk-free interest rate.

If a bank knows it can make risk free interest of 0.75% it will begin to charge customers with risk, loans to businesses and mortgages, more as a result.

By raising the interest rate paid on these accounts the RBA has increased the floor for economy-wide lending meaning higher interest rates will be passed onto everyday Australians.

$1.8 billion windfall for the banks

Banks won big on the raising of the interest paid on funds in the settlement accounts.

This is particularly true when you take into account the $188 billion the government lent to the big banks at the start of the pandemic the interest on which just tripled from 0.25% to 0.75%.

Australia’s biggest banks were offered billion in three-year loans for between just 0.1% and 0.25% interest starting in 2020. Most of this money found its way into the exchange settlement accounts which are now offering a tidy profit.

The risk-free gains on this money from Tuesday until the loan’s maturity is $1.83 billion straight from the RBA to the big banks.

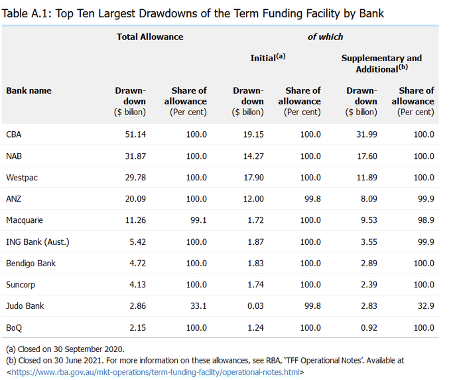

The biggest earner will be the Commonwealth Bank which drew down $51 billion from the Term Funding Facility and stands to gain approximately a quarter of the $1.8 billion now on offer from the RBA in the form of interest payments.

This profit should increase to around $3 billion by July. That’s a lot of money – risk-free – one of the consequences of the Ukraine war rocking the RBA’s otherwise well-navigated boat

Since the RBA’s announcement on Tuesday, there has been an increase in Exchange Settlement deposits.

House prices: what’s next

Australia’s variable mortgages are priced on the two and three-year bonds. The yield on these bonds was expected to rise in response to the RBA, however, the World Bank’s warning of below-average global growth was enough to take the heat out of yesterday’s RBA move.

Still, domestic banks have already moved to increase these rates with Westpac already passing on the rise ““From 21 June, Westpac will increase home loan variable interest rates by 0.50% per annum for new and existing customers,” it said in a statement on Tuesday evening.

According to Tim Lawless, research director for property group CoreLogic, the combined 75 basis points will add about $200 per month for a $500,000 loan compared with April.

Callam Pickering, former RBA and current Indeed economist, says that “Rising mortgage rates don’t guarantee that house prices will fall but a sharp rise in rates, combined with falling real wage growth, creates an incredibly challenging environment for the property market.”

The property market has already been slowing in the face of a wording economic outlook according to Pickering. “New mortgage lending fell by 6.4% in April – providing the first real sign of a slowdown in lending markets. Owner-occupiers were down -7.6% in April with First Home Buyers down -6.2% and Investors down 4.8%. Investor lending though is still 37% higher than a year ago, compared with -12.8% for owner-occupiers”.

Becoming your own landlord

Cameron Murray, a University of Sydney economist, says that the cost of housing will remain the same despite rising interest rates likely leading to lowering asking prices.

‘’There are two ways to reside in a house. Rent the house from a landlord or rent the money from a bank and become your own landlord. What happens when these prices are out of whack prices will change in the housing market to make them equal again. So if you put interest rates up, the cost of renting money goes up compared to the cost of renting a house and to make them equal again the price of the house must drop”.

So any way you cut it, the cost of residing in a house is likely to remain the same before and after these interest rate rises.

Higher interest rates are on their way

Further interest rate rises are expected, with Governor Lowe saying that: “The Board is committed to doing what is necessary to ensure that inflation in Australia returns to target over time. This will require a further lift in interest rates over the period ahead.”

With these rises, banks with billions in their exchange settlement accounts will see higher and higher risk-free profits.

Is the RBA tossing money at banks so they don’t stiff customers on rate rises?

Callum Foote was a reporter for Michael West Media for four years.