Some bastards are luckier than other bastards. Anthony Albanese is about to find out whether the curse of the new Labor prime minister will hold, writes Mark Sawyer.

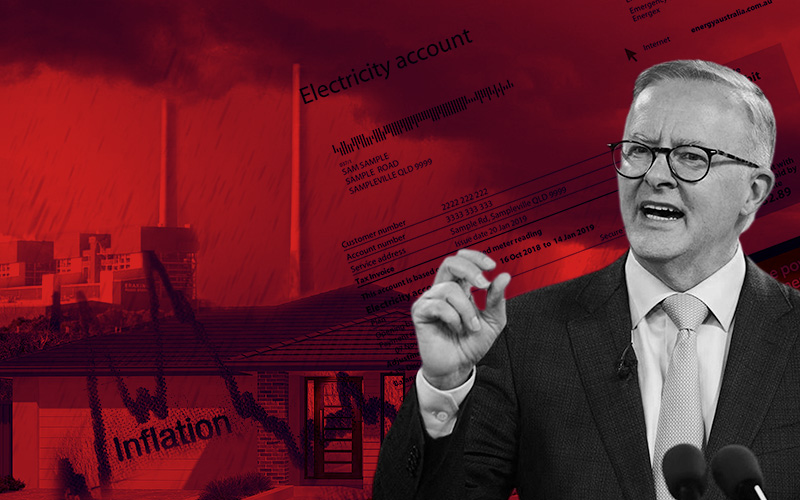

The anvil teetering over Wile E. Coyote or Elmer Fudd is one of the many endearing features of the Warner Bros cartoon. The anvil seems to be suspended by a string over the new Albanese government. The energy crisis afflicting the eastern states is but the beginning.

Take the Ukraine war, and the associated disruption to food supply chains. The outbreak of inflation not seen at these levels in four decades. The housing squeeze. Shortages of critical care workers. And the onrushing threat of climate apocalypse.

Labor is back in power. It is a rare gift. The ALP has held the reins of government for less than a third of the time in Australia’s history. And the party seems doomed to get the call from the electorate just as trouble is brewing.

Andrew Fisher won days into the outbreak of hostilities in the Great War in 1914. Jim Scullin’s team took office in October 1929, the month the Wall Street crash unleashed the Great Depression. John Curtin took over in 1941 as Japan was preparing to widen the war in the Pacific. Gough Whitlam’s ambitious program was derailed when the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 unleashed rampant inflation and unemployment in the Western world.

Bob Hawke had better luck, coming to power in 1983 as a long drought broke. During his time in office, the Berlin Wall came down. The Cold War waned (temporarily, alas). But Hawke had a tin bum, to quote Paul Keating, which apparently means he was a lucky bastard, Keating had less luck.

Bad luck returned for the next Labor government: Kevin Rudd was hit with the global financial crisis in 2008.

Anthony Albanese is going to need a change in fortunes, but the portents are not good. Even Albanese’s promise of ‘’an end to the climate wars’’ seems a little optimistic. And this time it might be Labor that is seen as the party dragging the chain.

Target: whose target?

The Albanese government was elected with a clear majority and a belated outpouring of affection. But it was the first election in 120 years of Federation where the opposition took power with a lower primary vote than the government it ousted.

And as MWM predicted, the excitement gathered around the climate independents (‘’Teals’’) and the Greens.

Labor has confirmed its vow to maintain its 43% commitment on emissions reductions by 2030. Already the word is afoot that Labor ditch and move closer to the targets advocated by the Teals (60%) or Greens (75%).

Labor is caught between its promises – a keeping of faith with the electorate – and the calls for expediency. The argument says, you won with a small target, but no need to worry about that, because, well you won. Winners do what they want.

It’s a curious argument to emerge from an election campaign where the word ‘’integrity’’ was so prominent, but it is the pressure that will be applied to a government with such a fragile mandate.

It will be fascinating to observe the media-savvy Greens and Teals decry Labor for keeping its promises after talking up the breakdown of trust in the two-party system, about truth in political advertising, about the whole ‘’integrity’’ bit.

A dance partner for Labor

Nonetheless it makes sense for Labor to move closer to the Greens as argued with MWM. The reason is simple: affinity.

The Greens are in part a product of Labor. Not entirely – there are many strands – but on economic policy the Greens share the ambitions of the old socialist left wing of the ALP. Absorbing this strand back into the centre-left ALP would be no picnic, but it remains a long-term necessity.

And considering Labor needs the Greens’ 12 Senate votes to pass any legislation opposed by the Coalition, it might make more sense to make nice with the Greens in the House.

There is another argument: that Labor marginalise the Greens by looking after the Teals. The case is based on the idea of the wedge. By giving an attentive ear to the concerns of the affluent, Labor can help the independents lock out the Liberals. It’s a case for an unholy alliance between the party of organised labour and the people who honed the concept of the unpaid intern.

The deal with Teals is meant to awaken voters in inner suburbs to the realisation that they don’t have to vote Greens to get action on climate and progressive economic causes. Vote Labor instead and you’ll get the same thing. Alas, that notion hasn’t worked in Melbourne. Greens leader Adam Bandt has held the former Labor stronghold under both Labor and Coalition governments for five elections. It didn’t work for Labor in Griffith. Terri Butler, who would have been Labor’s environment minister, was defeated by a Green who went big on local issues, particularly aircraft noise. Of the four Greens seats, two are ‘’natural Labor’’ and the other two have had Labor MPs (Ryan only briefly, admittedly). But the six Teal seats have never been Labor (three have seated an independent MP).

A threat to Labor unity

The external crises mentioned above have sometimes smashed Labor unity. It happened over conscription in World War I, economic policy during the Great Depression, and over communist influence in the unions in the 1950s.

In 1916 and 1917, Fisher’s successor Billy Hughes tried to enforce conscription, breaking up the ALP in the process. Disagreement over how to handle debts to Britain during the Depression split Labor. And a third split occurred in the 1950s, this time in opposition, over communist infiltration into the party. The latter split (nicknamed The Split) cost Labor the Catholic vote and extended its exile from office to 23 years. Labor has kept its splits in-house since then though it might be argued that the poisonous rivalry between Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard cost the party a third term.

Never underestimate Labor’s capacity to fall apart of its own volition. Meanwhile there’s an energy crisis to sort out.

Mark Sawyer is a journalist with extensive experience in print and digital media in Sydney, Melbourne and rural Australia.