The rate of increase in COVID-19 rose by 450 new cases on Saturday in Australia with a rise in new testing. The rate of acceleration in new cases had declined in the days before. It is too early to tell the right response to the pandemic – there is not enough testing yet – and it is too early to judge the effectiveness of the global response to COVID-19. It’s not too early though to start laying the groundwork for measuring our response and the critical data needed for the next pandemic. Research scientist, Tosh Szatow, reports.

It is too early to judge how effective – and proportional – the response to COVID-19 has been around the world. But with clear divergence in approach now showing by individual countries (compare South Korea and Sweden to those resorting to lockdown) and case growth rates now slowing in many countries (in Europe, Spain and Italy the worst, and Sweden, Austria and Norway the best) it is not too early to start laying the groundwork for how our response could be measured and assessed in time, based on critical data.

Not only does our preparedness for the next outbreak depend on it, but, so too, our ability to quickly assess and respond to acute risk. Agility is the friend of system resilience. The future belongs to those who write the history, and that history must begin with an accurate telling of the story.

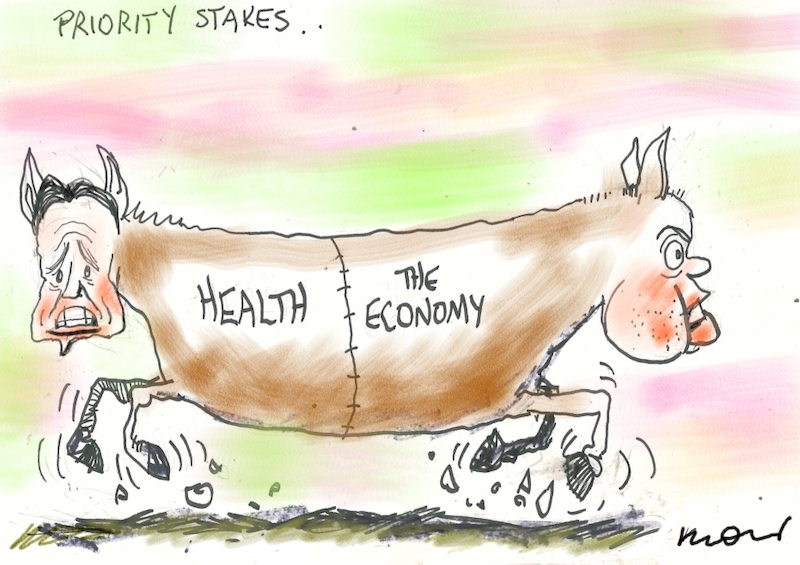

Illustration courtesy www.moir.com.au

This story begins with three key overlapping observations — the first two are objectively verifiable today, the third can be verified in time:

- WHO findings from the WHO-China joint mission clearly articulate that the infection rate and death rate associated with the original cluster of outbreaks in Wuhan was materially different to the subsequent spread in China. Specifically, transmission fell from 10% (resulting in R0-2-2.5) in the Wuhan cluster outbreak to a range of 1-5% (the range reported comes from three material data sets) or 2% when those data sets are taken in aggregate. That is a five times drop in transmission rate (see page 8-10, WHO-China joint mission report into COVID-19). We must ask which of those growth rates have been assumed in modelling the global response, and why.

- WHO findings were that testing, tracking and isolating cases and those at risk via close contact was key to success in China. It explicitly says that lockdown, including measures such as travel restrictions and school closures, were not the key to success (WHO assistant director general Bruce Aylward, March 16). It will be important to know when this finding first came to light, and at what point it became an official WHO recommendation, if at all.

- From my observation, it appears that our collective systems of interpretation and communication (expert commentators, university researchers, media reporters) have often overlooked points 1 and 2, when discussing COVID-19 risks in the public domain, and indeed when modelling its potential impact across society. I believe there has been a bias towards promoting lockdowns, drawing on authoritarian responses in Asia.

A detailed study would show if my observations are accurate, and whether it has influenced outcomes. If there has been an unjustified bias to using the Wuhan cluster outbreak for measures of death rate and transmission rate, including how these rates change with transmission type and response measures, it significantly affects our application of the precautionary principle.

Similarly, it also appears that expert commentators have failed to consider the downside of action to the economy and how it flows through to social impacts in particular. Job losses in an economic depression have very real, significant costs in human life and health. Even how we report on economic news can influence health (World Economic Forum).

Bearing those three observations in mind, what data should we gather now, for the investigation to come? I suggest there are five overlapping domains we will need to explore for data, unpack for meaning and analyse for recommendations, not only to make sense of the Australian response and the global context, but also to ensure history doesn’t repeat:

1. Tests, cases and deaths (how many and who) in relative and absolute terms:

This is obvious and simple, but it’s our best chance of stripping away noise in the evaluation of success. We need to understand how different countries responded in their application of testing regimes, case tracking and isolation of known cases. Low case rates with very low testing regimes could signal under-reporting of cases, particularly if coupled with high death rates.

Conversely, a very low death rate coupled with a disproportionate budget allocated to tracking and isolation and/or impingement of social freedom, has to be considered in how we define success. This data can be overlaid with decision timelines and other variables outlined below, to untangle correlation and causation, as well as demographic data that may provide insight into why some clusters have seen explosive growth, while others petered out.

2. The media response:

The media landscape has changed rapidly, and become profoundly important in how we step through messages, emotions and behaviour at the individual and collective scale. Undoubtedly, social media has played a major role in how we have managed the COVID-19 response to date, with hashtags such as #lockusdown in Australia being used to drive pressure on politicians.

No doubt Russian hackers and social media hit squads will have fake news attributed to them. But the reporting of data in the mass media is crucial, and it requires nuance. How is the word “exponential” used by reporters and interpreted by readers? How are we communicating subtle meaning like rate of change, compared to change in absolute terms, or key concepts like the precautionary principle that require balancing risks against costs of risk mitigation? In Australia,which countries are we drawing case studies from, for success and fear stories, and which are we omitting? And of course, what does all this tell us about our national psyche, in crises and in peace time?

3. Social and cultural norms:

I observe with caution, but it appears the role of social and cultural norms is being largely ignored, both in terms of their role in how this virus has spread, and how we have responded. And yet by definition, these norms define how we interact with each other physically and emotionally on a day to day basis. Awkward questions such as, does sympathy for a sick friend drive transmission (ABC reports from Spain — “A person died in our arms because we couldn’t get hold of oxygen”) lead to deeper ones such as, do we expect too much of our health system in keeping sick people alive?

A friend tells me in the Netherlands, ICU beds are rarely overrun as they prefer to let those critically ill die in peace at home. Or perhaps more flippant: is there a hidden downside to intergenerational families, or do the benefits of them in good times far outweigh the risks? And do our stress responses, in aggregate, help or hinder our response — who panicked into problems, who panicked into solutions, and why? For example, panic buying at supermarkets has likely increased the frequency and diversity of social contact during grocery shopping. But is that an arbitrary data point? Or can we find meaning in examples like it that will help us manage future pandemics and crises?

4. Country by country decision timelines:

Correlation does not prove causation, but it will be critical to map decision timelines against all other data sets. Are decisions being made after a build up of media pressure, and what impact are they having? Are they coinciding with systemic errors in reporting, or are they following expert guidance available at the time?

It will be critical to understand the role of “lockdowns” and all the grey they involve. Lockdowns and tracking regimes are typically coupled with invasive monitoring of citizen behaviour, and are likely to come at significant economic and social cost. So how effective are they? Were decisions to lockdown made in countries already experiencing declining case growth rates, and if so, why? Decision-makers are balancing many and varied priorities, and in a crisis, they deserve a level of sympathy where uncertainty is high. But where uncertainty is driven by a lack of preparation, poor institutional capacity, or institutional design, we need to apply a critical torch.

5. The role of experts and decision making

This is perhaps the most nuanced and difficult data set to track, but we can ask some simple questions to give clues for future preparedness: Are experts listened to by decision makers, and is advice available in time? More complex questions could reveal more fundamental, structural issues across the systems of education and media.

For example, were experts used to perpetuate media bias, or enhance meaning for readers, and what does this imply for education in journalism? Did experts themselves make systematic errors in interpreting data under pressure? Complex models can often be reduced to a small number of very important variables. Do our experts and institutions use sufficiently robust and diverse assumptions to arrive at decisive and accurate recommendations, or are we losing meaning in the complexity of the modelling journey?

Again, are our experts applying the precautionary principle in balance, or do silos across institutions lead to systemic bias such as omitting variables where modellers lack domain expertise?

Research shows that in certain situations (typically where uncertainty is high), domain experts make systematic mistakes in forecasting and decision making (see Harvard Business Review for an overview, and read further from there. Decision making research identifies strategies for enhancing decision making where uncertainty is high.

In short, it argues for the creation of diverse, non-expert teams scoring well on open mindedness, intellect and curiosity. These teams require access to experts for advice and feedback as they sift through the complexity and uncertainty. But decisions are best left to the non-expert teams.

What lessons are we learning, and how will they be applied when the next pandemic arrives? The groundwork for that response is critical.

Editor’s Note: At MWM we have favoured a lockdown hard and early response accompanied by a broad wage replacement scheme to protect workers until they returned to work. It remains too early to say which response to coronavirus is right. The latest data shows 3,636 cases in Australia and 14 deaths. Case numbers jumped in absolute terms, but growth rate continues to slow.

Tosh works as an independent energy consultant and has been a research scientist with the CSIRO, including overseeing complex inter-disciplinary research on the topic of distributed energy. He would argue that by being an open minded, curious and (arguably) an intelligent non-expert, research suggests he is well placed to reflect on the uncertainty and complexity of the Covid-19 response. Put him in a diverse group of similar people, and he may even make a useful decision when uncertainty is high. Time will tell how true that is.