Property developers indulge in all sorts of ways to limit construction and maximise profits – from building developments in stages to reducing the number of properties available to letting planning approvals lapse and then reapply for a higher density. It is economic incentives, rather than planning regulations, that limit the supply of housing, writes Dr Cameron Murray.

The same old tropes about the cause of high house prices are repeated ad nauseam – planning regulations are the problem; red tape is causing costly delays; restrictions on the type of buildings are the issue and so on .

According to a 2019 study from the Centre for International Economics study, commissioned by the Housing Industry Association of Australia, Sydney costs were higher because of greater delays from red tape. “Getting a Sydney housing development approved is just as hard as trying to get the go ahead for Adani,” HIA chief economist Tim Reardon was quoted as saying.

And now we have the Reserve Bank of Australia arguing that rezoning and getting rid of height restrictions are a magical solution. In their research paper released last week, “The Apartment Shortage“, RBA economists Keaton Jenner and Peter Tulip write that “building restrictions substantially increase the cost of housing” and that tall buildings are a substantially less costly way of increasing supply.

The report argues that the average new apartment in Sydney sells for $873,000 but the cost could be reduced to $519,000 if planning restrictions were lifted. If developers could add 20 storeys to their unit blocks across the inner city and eastern suburbs prices would drop.

But the assumption that the planning system drives up the cost of apartments is flawed. It is a huge distraction and buys into developers’ myths. This argument works for developers because it takes away the focus of the real cause. If there were a free-for-all for taller buildings, developers wouldn’t suddenly flood the market and crush housing prices. It is simply not in their interests.

Developers seek relaxed planning controls because it increases the value of the land they own.

Annual reports contain truth

And what developers claim in the media is quite often the complete opposite from what they say in their annual reports. That’s because developers are obliged to be honest with shareholders in these documents.

Developers never claim in annual reports that planning regulations are stopping them meeting housing supply targets. Often they say the opposite; that they are banking a certain project because they can get a better yield down the track.

It is widely believed that the supply of housing in Australia is not keeping up with demand because of planning regulations and that this lack of supply leads to overpriced housing.

Yet in a research paper published recently I show the complete lack of evidence for these assertions.

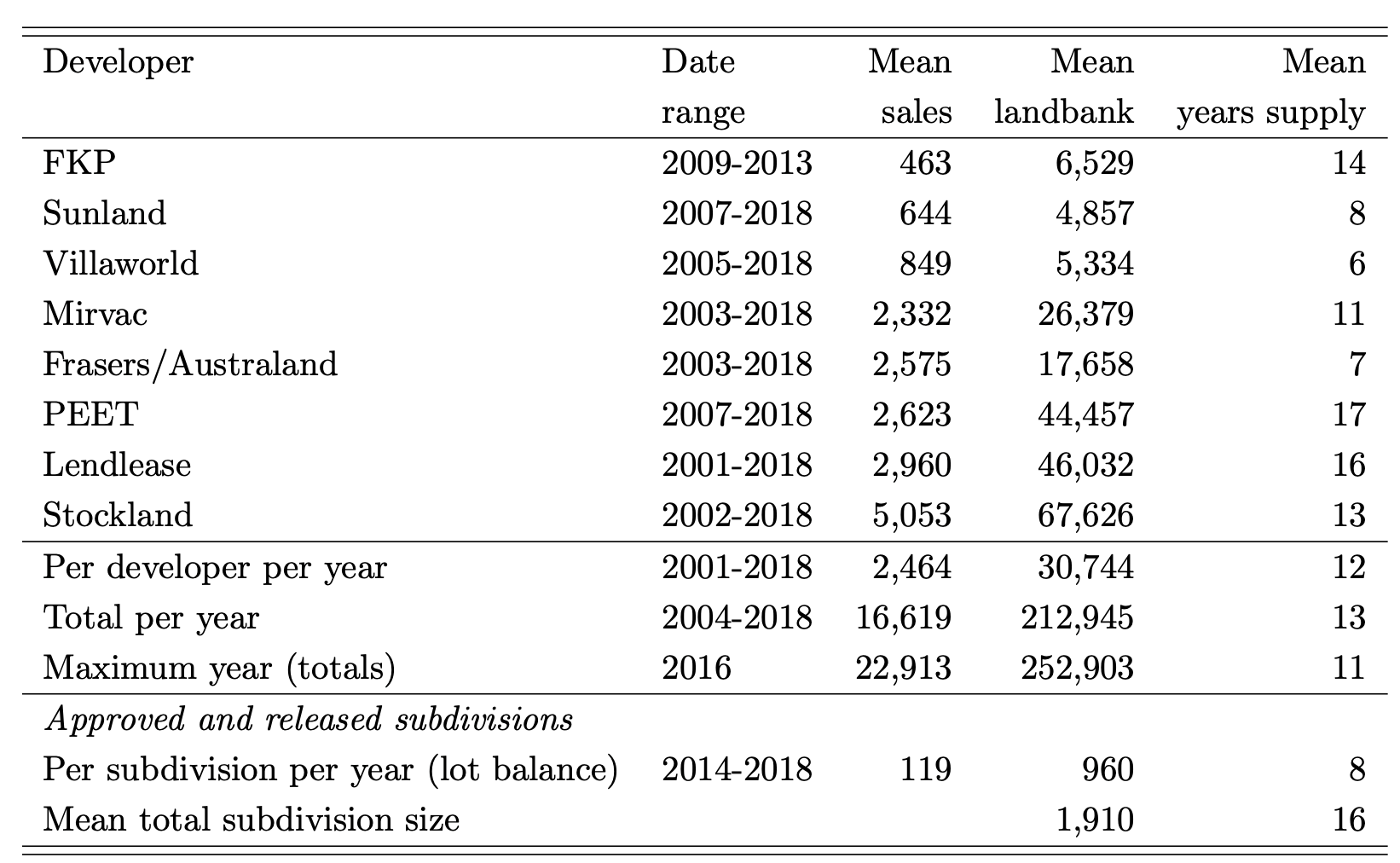

I trawled through the annual reports of Australia’s top eight listed housing developers, who represent about 9% of new housing supply. I tallied up their landbanks (the amount of land they are holding on to) and the number of sales of new homes and noted their strategic plans for housing releases.

While there is a widespread belief that there is limited land available for housing, the situation is quite the opposite. The developers are in fact holding on to a stock of supply that will take more than 12 years to sell at the rate they have been releasing them. It is an implausibly large inventory by any stretch of the imagination.

You might think that long lead times and planning delays are part of the reason for this enormous inventory.

To eliminate this explanation, I looked at just that subdivisions that were approved, where building had started, and where there had been at least one sale. The situation here is actually worse. The typical rate of sales from a subdivision once building starts is just 6% of the total lots each year, or a rate that takes 16 years to sell out on average.

So why the delay?

Lendlease provides an interesting example. The company’s sales rate approach is explained as follows:

“The Communities pipeline consists of an estimated 52,333 lots. With an annual target of 3,000 to 4,000 completions, more than a decade of supply has already been secured. The development pipeline provides long-term earnings visibility and the flexibility to be both disciplined and patient with the pursuit of future opportunities.” (Lendlease Annual Report 2018, p.76) (My italics added)

Similarly, developer Stockland reports that it has a landbank with a 10-year life expectancy.

Meanwhile, PEET Limited, a real estate development company notes in its 2017 annual report:

“The Group will continue to target the delivery of shareholder value and quality residential communities around Australia by leveraging its land bank; working in partnership with wholesale, institutional and retail investors; and continuing to meet market demand for a mix of product in the growth corridors of major Australian cities, with a focus on affordable product.

Key elements of the group’s strategy include:

- managing the Group’s land bank of more than 48,000 lots to achieve optimal shareholder returns; and

- an ongoing focus on maximising return on capital employed in all our key markets (My italics added)

Planning approvals renegotiated

It makes economic sense not to flood the market but to be patient. In fact, when I looked at state-wide approvals, the data clearly showed that during boom times, developers were more likely to let approvals lapse, delay projects, and later seek new planning approvals at higher densities.

Furthermore, state-wide approvals data shows that the land already zoned for housing does not correlate with the rate at which that land is converted into housing. This is further evidence that planning regulations do not limit the availability of land for housing.

Finally, the sorts of behaviour that private landowners and developers indulge in to delay construction also proves why it is economic incentives, rather than planning, that limit the supply of housing.

Ways to delay construction

For example, in addition to renegotiating planning approvals, other examples of delay include:

- building developments in stages. The land planned for a later stage could in fact be sold to other developers to build in tandem;

- reducing sales volumes rather than prices. Higher sales volumes could easily be achieved by reducing prices, which is what occurs in the wider market, when products are discounted to clear stock; and

- the fact that private landowners and developers choose when to make planning applications, and whether to seek approvals that are likely to be passed.

No one forces a landowner to seek approval for a development that conflicts with planning schemes. Regardless, even when councils approve planning applications, they cannot force landowners to then develop in a timely manner.

All of this behaviour is logical for developers. They seek relaxed planning controls not because it results in faster supply and lower prices — which, if true, would undermine their own profitability — but because it increases the value of their land.

They reduce sales in a soft market because it increases the total return to their land over time by not further depressing prices in a slump. If it is logical for developers to reduce sales when prices fall, then it is impossible to get supply-led price reductions from private housing markets.

Planners and policymakers need to be aware of this reality and not buy into the myth about planning, housing supply and prices. The evidence is all there. Developers tell their shareholders exactly how they behave. We just need to pay attention.

Cameron Murray is a research fellow in the Henry Halloran Trust at The University of Sydney. He specialises in property markets, resource and environmental economics, and corruption.

He is the author of Game of Mates: How favours bleed the nation.

Cameron's Twitter handle is @DrCameronMurray.

His website is: www.fresheconomicthinking.com