Large job agencies who dominate Australia’s privatised employment system are enjoying a boom of record profits, and even a takeover spree, while their disillusioned job seekers complain of churning and profiteering. Meanwhile, those in government on both sides of the political aisle are calling for reform. In this special investigation, Stephanie Tran reports on the failure of Jobactive.

As Australia’s unemployment rate soared during the COVID-19 pandemic last year, job agencies within the government’s privatised Jobactive system were tasked with helping Australians find work.

Ever since employment services were privatised under the Howard government, private unemployment services providers have sustained a litany of criticism, from allegations of widespread corruption, to bullying and the prioritisation of profit over the welfare of their clients.

*David, 34 has been unemployed for 11 of the past 16 years. Having dealt with Australia’s unemployment system extensively, he outlined his experience with the Jobactive system.

Between 2013 and 2017, *David was placed with Australia’s largest Jobactive provider Max Employment. Over the five years that he was with Max Employment, he alleges that they only put him forward for four jobs according to an FOI request he put in regarding the service he was provided with. He claims that only one of the four job referrals was genuine with the other three obtained without the help of the provider.

In 2015, *David attempted to enrol in a TAFE course to boost his qualifications. He claims Max Employment sabotaged his training and that he was advised by a consultant that “when they found out I had paid for the course they would make me come in to do an on-site job search and other appointments on the same days I was supposed to be at TAFE studying until I was forced to quit TAFE or they cut me off Centrelink for missing appointments with the provider, which would mean i couldn’t afford to go to the TAFE to study”

*David believes that Max Employment’s conduct was a result of the company prioritising profit over the welfare of their clients.

“Max Employment signed me up to a group ‘Work for the Dole’ activity within a month which would have made them $3,500 so I think greed was definitely a motivator for them.”

*David’s experience is not unique. Throughout our investigation we spoke to numerous sources, former employment consultants, policy experts and job seekers. Our call outs on Twitter and Facebook received over 200 responses detailing experiences of neglect, bullying and emotional distress at the hands of Jobactive providers.

The overwhelming consensus was that Australia’s unemployment system fails to adequately support job seekers, with punitive mutual obligations creating unnecessary stress on job seekers.

Findings

For-profit job agencies are the real winners in the system. From US-based multinational Maximus Inc to Liberal Party insider Sarina Russo, the companies that stand to benefit from the provision of lucrative multimillion dollar unemployment contracts are run by powerful individuals with significant political access.

Winners of the system (revenue of largest providers)

According to government tenders data between 2015-2022, the largest Jobactive providers (in terms of government contracts) are:

- Max Solutions $1.21 billion

- APM/Serendipity $667 million

- Sarina Russo Job Access $606 million

- Neato Employment services $257 million

- Sureway Employment and Training $221 million

- Atwork Australia $136 million

- Global Skills $91.3 million

- MBC Employment Services $90.5 million

- Peopleplus Enterprises $84 million

Source: Per Capita

Foreign ownership

Four of the ten largest Jobactive providers are owned by foreign multinationals.

Max Solutions

Max Solutions is owned by American multinational Maximus Inc. The company is listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) with a market cap of $US5.64 billion.

APM and Serendipity

Serendipity is wholly owned by APM. The ultimate holding company (UHC) of both companies is APM Human Services International Pty Ltd. A large proportion of the shares of the UHC are held by foreign individuals or companies based in the US, UK and Austria.

Atwork Australia

Atwork Australia is owned by Gold Parent LP, an American investment company based in Delaware.

Financial secrecy

We went through the financial statements of each of the largest providers. A number of these had complicated share structures with shareholders in multiple foreign countries.

Throughout the pandemic, many Jobactive providers experienced little to no impact on their solid streams of government revenue. The US based parent company of Australia’s largest Jobactive provider Max Employment described how their contracts were amended by the Australian government to maintain their profitability.

“Many of our contracts were modified to more favourable terms as a response to the pandemic. In Australia, the balance between administrative revenue and outcome-based revenue was adjusted to reduce the risks within the contract.”

They also boasted an “estimated revenue growth of approximately $US175 million in fiscal year 2021”.

Stay tuned for our roll out of profiles on the largest jobactive providers where we will go into detail about how the individual companies operate.

How the system works

Privatisation

In 1998, the Howard government privatised the Commonwealth Employment Service (CES). The shift towards the fully privatised “Job Network” model spelled an influx of for-profit providers.

According to Per Capita, “The privatisation of unemployment services has created “a herd of profit maximisers who are highly responsive to threats to their viability and who embrace standardisation of services as a way to minimise risks”.

The privatisation of employment services continues to attract significant criticism to this day. Throughout our investigation, we spoke to numerous former CES employees. Many described the changes in the quality of employment services as they shifted to a privatised model.

Annette Morrow worked in CES offices across Sydney between 1969 and 1974.

“I believe it should be back in the hands of well-trained employment officers as we were in the CES, prior to privatisation … Profit was not our focus; getting people into and filling job vacancies was our focus.”

“These days there is little concern or real focus upon the true clients: jobseekers and employers. Adhering to government lines and profit seems to be the main focus by most providers running these businesses”

Business model of the providers

Jobactive providers make revenue from both administration fees and outcome fees.

- Administration fees

Jobactive providers receive $377.30 every six months for all enrolled job seekers aged under 30 and $269.50 every six months for all other enrolled job seekers.

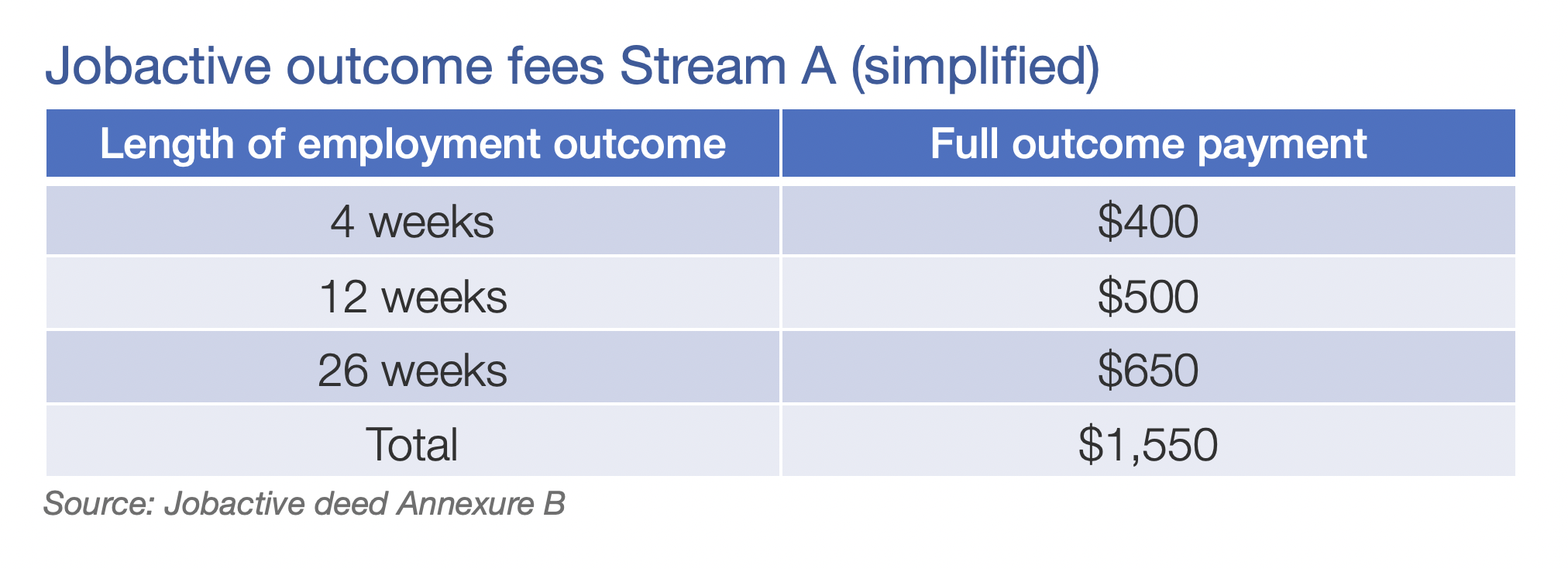

- Outcome fees

Jobactive providers receive outcome fees based on the duration of employment

Source – Per Capita

Fail safe profits

Job seeker providers are part of a lucrative, heavily protected industry. The business models of unemployment providers carry little to no risk as their income is guaranteed through government contracts. During the pandemic last year, the government amended the funding model of Jobactive providers, increasing administration fees from $350 to $547 for job seekers under 25 and $250 to $391 for all other jobseekers.

Increased profit during pandemic

Last year as Australia was plunged into a recession and unemployment soared, Jobactive providers reaped in hundreds of millions of dollars from increased caseloads. Analysis from Per Capita estimated that fees paid to Jobactive providers between June and November 2020 totalled approximately $360 million. This figure reflects a $150 million increase in administration fees from the $210 million normally allocated for a 6 month period.

Failures in the current model

Throughout our investigation we spoke to numerous former employment consultants, policy experts and job seekers.

A theme we encountered consistently was that the current model fails to provide meaningful support to job seekers. This failure is underpinned by a funding model that encourages privatised jobactive providers to “cream and park” job seekers. This practice involves providers assisting job seekers they deem easy to place into work enabling them to claim outcome fees (“creaming”) and “parking” job seekers that require more extensive help as it is simply not profitable to assist these people.

Assistant National Secretary of the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) Michael Tull criticised the conflicts of interest within the industry.

‘The current system does not work. It’s a mire of conflicting interests where job seekers often come off second best to the provider’s profit motive. And the current employment services system has to be seen and understood as part of the very punitive approach to social security in this country – with providers playing a key role in policing mutual obligations. There’s no evidence that mutual obligations deliver better outcomes, and plenty of evidence that it leads to misery for job seekers. The time and resources going into policing the system are time and resources not spent on helping job seekers or employers”

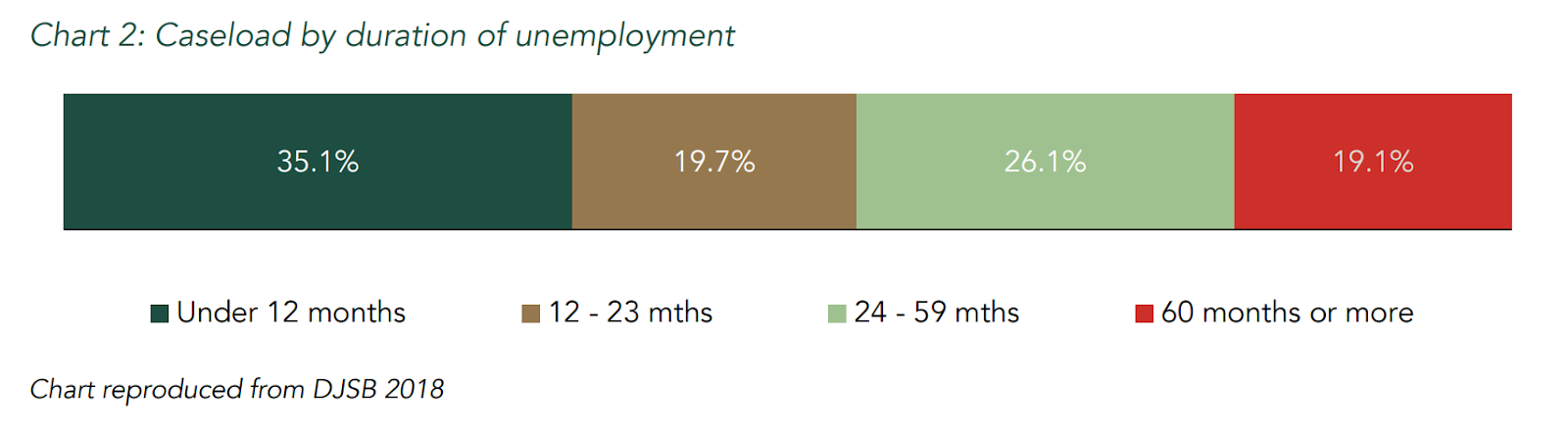

The numbers paint a grim picture. Long-term unemployed (those who have been unemployed for 12 months and over) make up 65% of caseloads, with 19% of job seekers being unemployed for over 5 years.

source – Per Capita

Senate Inquiry – “welfare to nowhere”

A 2019 Senate Inquiry into the Jobactive model found that the “current funding model incentivises jobactive providers to churn people through short term work, rather than helping them to secure sustainable longer-term employment”.

The report was critical of negative effects of the funding model stating that “when people cycle in and out of short term work, their jobactive provider can continue to receive outcome payments. Providers are rewarded financially for churning people through jobs that don’t last”.

The findings of the report are best summarised by the following scathing assertion, “Jobactive is not welfare to work, it is welfare to nowhere. The government’s punitive and paternalistic approach to employment services has failed.”

This special investigation has been partially funded by GetUp. The full report on Jobactive by Stephanie Tran will be available shortly.

Pandemic goldmine for private unemployment agencies as Coalition boosts payments

Stephanie is a journalist and has a law/journalism degree. She was a finalist for the 2021 Walkley Student Journalist of the Year Award and the winner of the 2021 Democracy's Watchdogs Award for Student Investigative Reporting.