After months of clutching its collective pearls over the allegedly “tight” labour market, the RBA board gets what it wanted: more unemployed people. Michael Pascoe writes.

Contrary to numerous headlines, there is no surprise about the labour market weakening and unemployment rising, as demonstrated by last week’s ABS numbers. It’s not a surprise because it has been RBA policy.

Also contrary to various headlines, the RBA doesn’t “suddenly” look late in cutting interest rates. It’s been late for nearly a year, ignoring all the data showing inflation was in retreat, the economy was soft and that an unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent wasn’t causing inflation.

“But but but,” the RBA will stutter, “business told us the labour market was tight”. What the RBA failed to grasp is that the labour market hasn’t been too tight, that being a bit tight is actually a fine thing, that competing for labour helps improve productivity by encouraging investment in capital on one hand and winnowing out the least productive enterprises that can’t compete.

But that’s a bit of the productivity story the business lobby and its media stenographers don’t like to touch. It’s Darwinian and dreadful for the individuals who lose their savings and businesses, but it’s what capitalism requires to work.

You know all the stories about “record number of business failures” last year? None of them mentions that there was a greater number of business startups. None of them mention that in a “tight” labour market,

resources are freed up to be better used elsewhere.

But I digress.

Rate cut failure

The failure to cut rates earlier this month is now obviously embarrassing for the six members of the RBA board, including the Governor, who voted to continue squeezing the economy, thereby weakening it with contractionary monetary policy. It will be more embarrassing if the June quarter CPI comes in as tame as the RBA itself expects.

There is a certain irony in the “new improved” Monetary Policy Board’s first outing, with its greater emphasis on communication, producing such a communications blunder.

If the RBA was prepared to own its mistakes instead of prevaricating, the next meeting’s statement should be headlined “We Wuz Wrong”, but it won’t be.

The three members who voted to cut this month, the three who seem to have a better idea of how monetary policy works and where the economy is at, can rightly say “we told you so”.

The dangerous question is whether the other six will humbly agree or claim that, no, the rise in unemployment is exactly what they were hoping for as the labour market is ”tight”.

The danger is that the majority will run a metaphorical victory lap at next month’s meeting, pointing to inflation and the labour market being where they want it.

Lessons not learned

It’s dangerous because it ignores two high school economic lessons.

First, that monetary policy works with a long lag. The weaker economy and labour market are the result of rates being tightened and kept tight over the past two years. The ship slows and turns very slowly, so the weakness trend will continue past hitting the target.

Second, employment is a lagging indicator. The “sudden” softness in the employment stats comes months after the economy overall was flashing amber, but the RBA ignored that.

The RBA’s biggest worry now is that it will overshoot its tight little trimmed mean inflation target on the downside. The ship is very slow to turn.

That would again seriously damage the bank’s credibility. Michele Bullock could follow Philip Lowe in being a one-term governor.

The question unsuccessfully dealt with by the board over the past year is why it needed higher unemployment, other than business asking for it. As previously opined, the RBA now goes to considerable effort to monitor multiple indicators under a vague “full employment” heading to avoid the simple reality of the old NAIRU (non-inflation-accelerating rate of unemployment) it never managed to get right.

Unemployment rate steady

As an economist friend noted in frustration, since December 2023, in all but two of 18 months, the unemployment rate has been within 0.1 of 4.0 per cent, as steady as any economic series is likely to be.

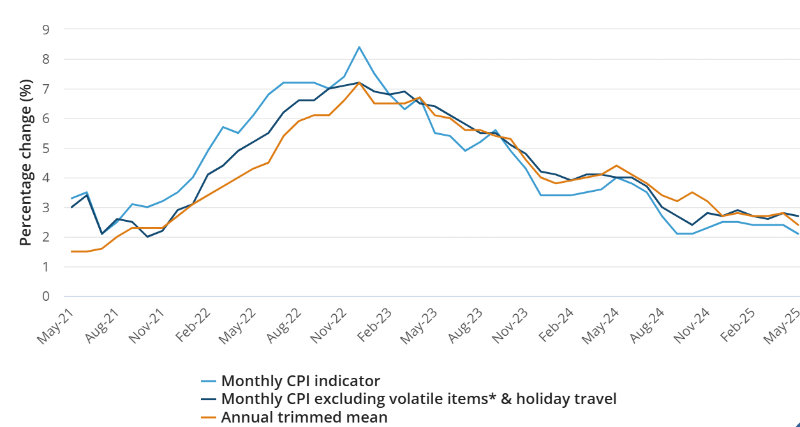

In that time, all serious measures of inflation have plunged. The trimmed mean quarterly CPI is down 1.3 percentage points to 2.9 in March. The monthly trimmed mean CPI is down 1.6 percentage points to 2.4 per cent in May. The wage price index is down by 0.9 percentage points to 3.4 in March.

I’d go a step further and argue, as I did at the time, that increasing the cash rate by 25 points in November 2023 was a mistake, an unnecessary tightening when the trend was already our friend.

Source: ABS

With the ABS monthly CPI indicator within the target zone since last August, taking the foot off the monetary brake should have been top of the RBA’s agenda, but the bank instead waited for February for its first tentative move, failed to move again in April and again failed to follow through on the May cut.

Should the economy do what it’s now expected to do, get weaker,

nobody on the RBA board can claim the writing wasn’t on the data wall.

But they will. You know, the old “the outlook is uncertain” line.

Michael Pascoe is an independent journalist and commentator with five decades of experience here and abroad in print, broadcast and online journalism. His book, The Summertime of Our Dreams, is published by Ultimo Press.