Are doctors over-servicing? Are millions of people worldwide receiving stents with no benefit? Are all patients providing their “informed consent” for surgery? “It’s a divisive area within the specialty because it threatens a lot of cardiologists’ incomes,” says one doctor. Coronary stents are a multi-billion-dollar market, a market which is rapidly expanding. Investigative reporter and medical science specialist, Maryanne Demasi, investigates.

Since their introduction in the mid 1980s, coronary stents have proven to be life saving in emergency situations such as in the event of a heart attack.

More recently however, stents are increasingly being used in non-emergency situations such as “angina”, where people experience chest pain or shortness of breath when climbing up stairs.

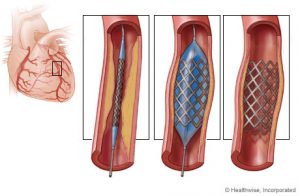

The procedure involves inserting the stent — a wire mesh scaffold — inside an artery, to widen up the space inside the vessel and restore blood flow (see picture).

The rationale for using stents in people with angina is that opening up a blocked artery (due to plaque accumulation) will alleviate chest pain.

But a new study has cast significant doubt on the value of using stents to treat angina, leading some doctors to believe that millions of people are receiving stents, with little benefit.

Are stents for angina unnecessary? I investigate the ongoing controversy where millions of dollars and reputations are at stake.

A costly business

The coronary stent market is expected to reach $US15.2 billion by 2024. In Australia, approximately 28,131 procedures involving stents were performed last financial year, up from 21,472 a decade earlier — a 31 per cent increase.

According to NSW Health, the average cost of an angiogram and insertion of a coronary stent is $16,900 so we now spend an additional $112 million a year on this procedure. Undoubtedly, stenting is big business.

Stenting makes sense – doesn’t it?

Intuitively, stenting a blocked artery makes sense. Here’s a common scenario:

A patient has chest pain. The doctor discovers a blocked artery during an angiogram. While the patient is awake on the table (but mildly sedated), the doctor shows the patient the blockage and decides to use a stent to open up the artery. The patient is hugely relieved because their blocked artery has been “fixed” and they thank the doctor for saving their life.

A US survey published in Annals of Internal Medicine showed that 88 per cent of people receiving a stent believed it would reduce their risk of a future heart attack or stroke.

But Dr Aseem Malhotra, a cardiologist who has performed hundreds of stent procedures and currently works as a consultant for the National Health Service (NHS) in London, says this is a common misunderstanding.

“Stenting a narrowed artery does not prevent heart attacks, strokes, nor does it prolong life in people with angina,” says Dr Malhotra. If they are told otherwise, it’s simply untrue for the vast majority of people”.

Dr Jason Kaplan, a Sydney based cardiologist from Macquarie University Hospital agrees. “The majority of patients who get a stent for stable angina think, ‘oh, I was lucky they found the blockage before anything [bad] happened’…. but it’s not always the case,” says Dr Kaplan.

In 2007, a seminal study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (COURAGE trial) showed that a stent in people with angina failed to reduce their risk of heart attack or stroke, nor did it prolong their life. The results rocked the cardiology community.

“We were shocked actually. We were surprised because we were stenting patients with the idea that it would reduce major cardiovascular events,” said interventional cardiologist Dr Rasha Al-Lamee, of the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

“Initially, we saw a drop in the number of procedures being performed but it eventually went back up again because our patients would tell us that they felt better after the procedure,” says Dr Al-Lamee.

What should have been a game-changing trial, was eventually abandoned by cardiologists who continued to put stents in people with the belief that, at least, it helped treat angina symptoms like chest pain. But, this had never been properly tested — until now.

A coalition of researchers at Imperial College in London, led by Dr Al-Lamee, conducted a unique clinical trial to find out.

“The study was the first of its kind where we wanted to see whether the relief of symptoms that our patients report was due to the therapeutic effect of the stent or whether it was due to placebo,” said lead researcher Dr Al-Lamee of Imperial College in London.

The ORBITA trial analysed two hundred people with angina who had an artery showing at least a 70 per cent blockage. Participants were given either a stent or a “sham” procedure (the equivalent of a surgical placebo) on top of their usual angina medications. To overcome any bias, neither the patients nor the researchers knew who was given a stent or placebo.

Six weeks later, the participants were put through their paces and assessed on a variety of measures including exercise and symptoms relief. The results of this landmark study reverberated across the cardiology community.

“Surprisingly for all of us, after 6 weeks there was no significant difference between the two groups when assessing capacity to exercise or symptoms of chest pain,” said Dr Al-Lamee.

Essentially, the coronary stent did not prove superior to placebo. “However, we did find the patients who had the stents showed improved ischemia. That is, the blood flow to the heart of these patients did improve,” said Dr Al-Lamee.

Dr Al-Lamee says it’s still not clear whether stenting a vessel and restoring blood flow has any significant benefit for the patient. A more definitive study, called ISCHEMIA, will be completed later this year.

How can unblocking an artery not make a difference?

“The narrowing happens so gradually that there is enough time for the heart to grow collateral blood vessels to compensate for the narrowed vessel,” says Dr Malhotra.

Another reason why stenting may not reduce the risk of a future heart attack is because stents are usually implanted in arteries where the narrowing is over 70 per cent.

However, most cardiac events occur at sites on the coronary artery where there is less than 70 per cent narrowing. So it is highly likely that doctors are stenting areas that would never have caused any harm.

ORBITA has cardiologists divided

Some cardiologists dismissed the trial saying it was too small to consider making any changes to current practice. Also, the follow up of six weeks wasn’t long enough to see any beneficial outcomes.

Others said that, in their experience, patients often want to have a stent, instead of taking angina medications for chest pain, which come with side effects like fatigue, dizziness and palpitations.

Conversely, other cardiologists have claimed the study is the ‘last nail in the coffin’ for using stents to relieve chest pain. “This is mind-blowing,” said cardiologist and Lown Institute president, Dr. Vikas Saini. “For cardiologists, this is like saying that penicillin doesn’t work for infections.”

Dr Al-Lamee believes the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

What are the risks?

According to TheNNT.com, one in 50 people who receive a stent for angina experience a serious complication such as death, stroke, heart attack, arrhythmia or haemorrhage. Hence, in the absence of benefit, the risks of receiving a stent for angina become paramount — especially if the procedure is unnecessary.

“I have no doubt that people have died during a stenting procedure, or have had a heart attack or stroke, who should probably never have undergone a procedure in the first place,” says Dr Malhotra — “or at the very least, have changed their decision to have the procedure done if they were told it wasn’t going to improve their prognosis”.

“Some patients prefer to have the stent put in, knowing about the risks because they don’t want to be on the anti-anginal medications for the rest of their lives and are willing to take the risk,” says Dr Al-Lamee.

Incentive to stent?

The Australian Medicare system is a government funded “fee-for-service” system. While it is highly regarded, this system is also vulnerable to “over-servicing” where doctors may provide unnecessary or inappropriate medical therapies.

A recent article in The Lancet said more needed to be done to address inappropriate medicine, which included deliberate over-servicing by doctors for their own financial gain.

Dr Malhotra is a member of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Choosing Wisely Steering Group campaigning to wind back the harms of unnecessary procedures and medicines.

“It’s a system failure that incentivises doctors to do more procedures, and their decision to stent a patient will be biased and unjust at times,” says Dr Malhotra.

A small US survey, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine claimed that 43 per cent of cardiologists would still implant a coronary stent, knowing that it had no benefit for the patient.

“I believe most doctors want to practice in an ethical way but I have no doubt that there is a small minority of cardiologists who are practicing unethical medicine,” says Dr Malhotra.

For example, a US cardiologist admitted to ordering US$19 million worth of unnecessary investigations and procedures, leaving many patients with false diagnoses of artery disease and angina. Unnecessary stenting for stable coronary artery disease has been estimated to cost the US healthcare system $US2.4 billion.

“Ultimately, I don’t think Australia’s fee-for-service model is in the patient’s best interest as it rewards doctors for doing procedures and interventions, where sometimes, not doing the procedure is the best thing for the patient,” says Dr Kaplan. “It’s a divisive area within the specialty because it threatens a lot of cardiologists’ income”.

Patient consent

This raises concerns about whether people are giving “informed consent” when accepting medical procedures. Transparent discussions about the risks and benefits of a procedure can change people’s decisions about whether or not to accept a medical therapy.

For example, one study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, showed that people were 20 per cent less likely to receive a stent when they were told explicitly that a stent would not reduce their risk of a heart attack. Hence, it was estimated that 20 per cent fewer stenting procedures in the US could represent a potential saving of $864 million in one year.

In 2014, Dr Malhotra was the first cardiologist to call for patient consent forms to have a mandatory disclosure stating that stents offer “no prognostic benefit in the treatment of stable angina”. At the time, Sir Prof Terence Stephenson, now Chairman of the UK’s General Medical Council, backed the calls.

“We need to empower patients with the principles of Choosing Wisely. That is, asking their doctor, ‘Do I really need this procedure? What are the risks? What happens if I do nothing? And are there alternatives? If every patient asked this question to their doctors before they had a procedure or medication, a significant proportion of our health care crisis would be solved,” says Dr Malhotra.

“We need bravery for frank conversations with patients about the uncertainty in medicine,” wrote a group of cardiologists in a recent paper. “We should not forget the old surgical adage; a good surgeon knows how to operate, a better one knows when to operate, and the best know when not to operate”.

——————-

Dr Maryanne Demasi

The author, Dr Maryanne Demasi, is a PhD Rheumatology and has reported extensively on statins and diabetes and the sugar lobby.

Maryanne can be contacted on Twitter at @MaryanneDemasi

This story is not medical advice; it is a journalistic investigation.

Statin Wars: how Big Pharma infiltrates governments and the medical profession

Dr Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in Rheumatology. She has done a number of important stories for michaelwest.com.au including investigations into the infiltration of the medical profession by processed food companies and the over-prescription of statins.