“Some providers are taking up to 53 per cent of the package in fees. Other providers only take about 10 per cent,” writes public health researcher and Director of Aged Care Matters, Dr Sarah Russell. While the media has been reporting stories of appalling treatment in aged care homes, Russell is publishing her research on another aspect of aged care this week — home care packages.

THE STORIES about in-home care are equally appalling, albeit for different reasons. What is heartbreaking – and currently flying under the radar – is the commodification of the treatment of older people, the rorting in the system, insurance companies with no experience of caring for older people winning contracts to provide in-home care, strangers being sent to the homes of older people, and support workers with minimal or sometimes no training.

The only aspect of in-home care that makes the news is the ridiculously long queue for home care packages. Some 127,000 older people are waiting to be assigned a package, with some waiting more than a year.

I recently interviewed the lucky ones — older people who had received their home care package. I asked them and their family about what is working well, and what is not. The research is timely because the Living Longer Living Better (2013) and Increasing Choice in Home Care (2015) reforms have significantly changed the way in-home support is delivered.

The Commonwealth Department of Health is clear about where the aged care reforms are headed. It envisages a future where the aged care system is consumer driven, market-based and less regulated. Where the public might view an older person as needing support as they age and become more frail, the department aims to transform them into an empowered “aged care consumer” — to position older people as active participants in an economic transaction.

The first challenge facing “aged care consumer” is how to choose one of the more than 860 government-approved home care providers — preferably one that delivers high standards of care at a reasonable price. Many older people simply do not know where to start.

They soon learn that the only place to start is with My Aged Care, established in 2013 by the federal government as a “one-stop aged care shop”. Previously, GPs and local councils had been the first port of call. Now older people begin their “aged care journey” by phoning My Aged Care or, for those who are computer literate, by visiting its website.

96yo approved for home care, waiting more than 9 months w/out assistance. Daughter: "I watch the news & I read the newspapers. But what the govt says is, ‘blah, blah, blah' – this is my reality" https://t.co/034mVmGVE2 #agedcareRC #CDC

— Aged Care Crisis (@agedcarecrisis) February 27, 2019

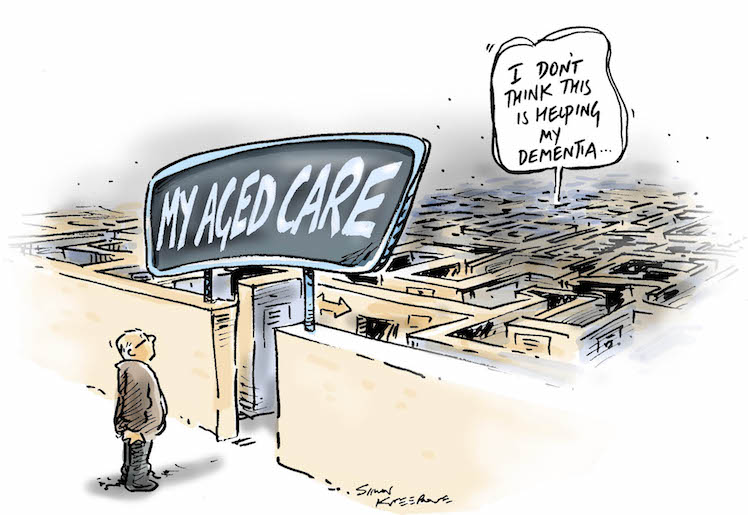

My Aged Care has been such an unmitigated disaster that six years after it was introduced, an Aged Care System Navigator is being trialled to help people “navigate” the aged care system. The absurdity of needing a second service to assist people to use the first service brings to mind an episode of Utopia.

“Navigate” has become the new buzzword in aged care. The first discussion paper from the Royal Commission is titled: Navigating the maze: an overview of Australia’s current aged care system. But it was not a maze when local councils, the Royal District Nursing Service and other not-for-profit and for-profit organisations delivered services to older people in their home. How did the aged care system become so complex that older people and their family need help to navigate it?

Social isolation among older people is emerging as one of the major issues facing the industrialised world. One of the priorities of the aged care system should therefore be to ensure older people remain engaged in their communities. Many councils recognise this and have developed Active and Healthy Ageing Strategies. One strategy involves providing subsidised activities for older people – such as senior citizen clubs, activity groups, men’s sheds and community bus trips.

However, some federal government bean counter is concerned about older people ‘double dipping’ by using subsidised federal services as well as local council/state government services. As a result the federal government introduced a policy of “full cost recovery”.

Under this policy, those receiving a higher level home care package (i.e. a federal subsidy) are required to pay the full cost of activities subsidised by their local council. While older people using the Community Home Support Programme pay the subsidised rate of $10 for a bus trip, those with a higher level home care package pay $100 (i.e. the full cost). This $100 is deducted from their home care package. Such exorbitant costs have forced some older people to stop going to local social activities because they may then have less in their package to spend on personal care, for example.

This brings me to concerns about the financial statement the “aged care consumer” receives each month from their provider. These statements are often long and difficult to understand, creating unnecessary stress for older people and their families. It is also difficult for the “aged care consumer” to know how much a provider should charge for labour, equipment and supplies.

The monthly financial statements indicate some clients are being charged a fixed cost for case management, irrespective of how much case management they use. The costs for case management vary enormously, with some providers taking up to 53 per cent of the package in fees. Other providers only take about 10 per cent. The wide range may indicate differences in the health needs of the older person and the complexity of providing case management. Or it may suggest overcharging.

Cartoon by Simon Kneebone

The Minister for Senior Australians and Aged Care, Ken Wyatt, asked all home care providers to publish their existing pricing information on the My Aged Care Service Finder by November 30, 2018. Several providers have not yet done so.

There are also significant differences in the hourly rates providers charge the “aged care consumer” for support workers — from $39 to $61 an hour on a weekday. Some providers charge the “aged care consumer” more than $130 an hour for a support worker on a public holiday. Yet it’s fair to say the support worker would have received only a fraction of that rate.

There are also large differences between the support provided by different providers for the same amount of money. For example, some providers deliver just 10 hours of personal/domestic support per week to those on a Level 4 home care package while other providers deliver 30 hours. How can these differences be justified? It has been suggested they are a result of the market-based system that has been established explicitly to create competition, innovation and choice for the “aged care consumer”.

Questions must also be asked about unspent funds. How many older people are not spending their monthly subsidy due to the poor quality of the services provided? When the support workers change from day to day, some older people may prefer no one to provide personal assistance given their concerns around safety.

Large companies with limited or no expertise in the delivery of aged care services have also been given licences to provide aged care. It is not surprising that a company that specialises in insurance, for example, would deliver unsatisfactory aged care service. It is, however, surprising how many large established aged care providers also deliver an unsatisfactory service.

The most common complaint about home care providers is the high turnover of unqualified, inexperienced and untrained support workers. A high turnover of staff is a recipe for disaster. It results in strangers being sent to work in an older person’s home. The older person has to just trust that they will be treated with respect and kindness.

Many older people have high expectations for the services that will be provided by a home care package. They hope these services will enable them to remain in their own home. Those with the best outcomes have family support, most often a daughter. Without this additional support, many acknowledged they would not be able to remain at home.

Earlier this year, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety began hearings. This Royal Commission is investigating both residential and in-home aged care.

Factors that are important to older people who receive a home care package

- Access to a competently staffed My Aged Care information line/web page to provide accurate and consistent information and advice;

- A clear explanation of providers’ services including their fees;

- Publication of providers’ fees and charges on the My Aged Care website;

- Clear information about entitlements and reimbursements;

- Information on sub-contracted services, including rates and any additional charges;

- A home care agreement that is easy to understand;

- Reasonable fees for case management and administration;

- Reasonable charges for support workers;

- Support workers who are paid the award rate or above;

- Reasonable costs for equipment and home modifications;

- Reasonable charges for gardeners and other maintenance personnel;

- Clear financial statements that accurately reflect the services provided;

- Person-centred care delivered by a local provider;

- Support workers who are suitably trained, competent, trustworthy, punctual and empathetic;

- Knowledge about the qualifications and experience of staff;

- An option to choose support workers;

- Consistent support workers who work at regular and set times (e.g. 9am rather than sometime between 9am and 11am);

- Flexibility with times and changing needs;

- Access to service provision “on the spot” (i.e. same day) when a situation changes (e.g. transport to a doctor’s appointment);

- Sufficient time allocated for support workers to undertake tasks required;

- Direct communication permitted between recipient and support workers for easier co-ordination;

- A weekly roster of support workers supplied in advance;

- Case managers who are experienced, qualified and easy to contact;

- Consistent use of mutually agreed means of communication with case managers (e.g. emails, messages, home phone or mobile);

- Information about how many older people case managers are overseeing;

- Forward-thinking case managers who seek to improve care and offer suggestions if new services become available;

- Regular mandatory visits by case managers to include health/welfare checks, face-to-face conversations and updates with the older person.

- Better-trained office staff (e.g. how to talk respectfully to older people, including older people with dementia);

- Options for different degrees of case management support/self-management;

- Involvement of family/advocates when issues arise;

- Ongoing professional development, including dementia training, for all staff;

- Access to affordable social activities inside and outside the home;

- Provision of information from case managers on other community resources (e.g. local services, volunteer groups etc.)

- Feedback from older people and their family/advocates welcomed by providers; and

- An effective complaints process.

———————

Report calls for “Visibility” as bankers swarm around Aged Care

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

Dr Sarah Russell is a public health researcher. She is the Principal Researcher at Research Matters and Chair of Progressives of the Peninsula. She was formerly the Director, Aged Care Matters.