The Coalition won the 2013 federal election beating their chest about Labor’s “debt and deficit”. Thanks to COVID-19, we’re unlikely to see a surplus in our lifetime or our children’s. But, let’s not forget that the current debt blow-out occurred well before the coronavirus impacted the economy. Alan Austin checks how Australia shapes up against other OECD countries.

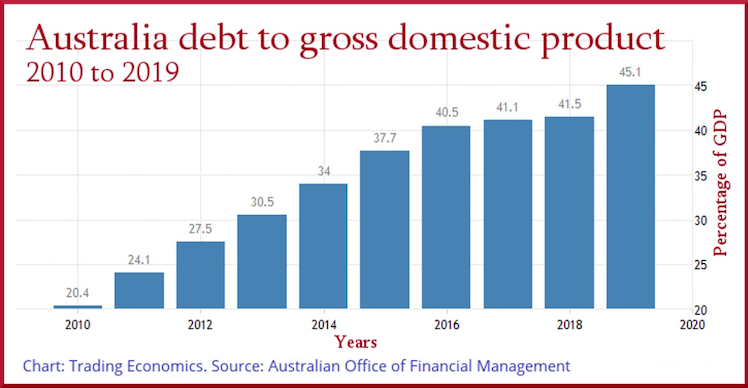

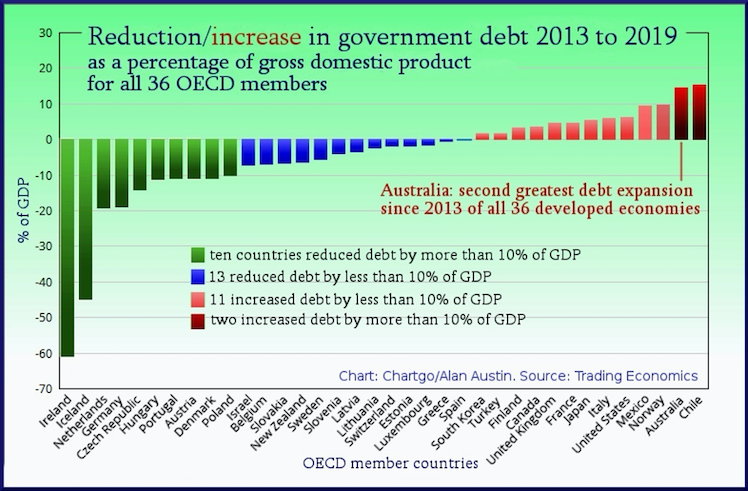

We now have government debt figures for nearly all the highly developed capitalist economies for 2019. Two stand out as having stacked on far more debt than the others. They are Chile and Australia.

Of the 36 wealthy members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) the majority has taken advantage of the recent global boom in investment, trade and government revenue to pay back debt amassed during the global financial crisis (GFC).

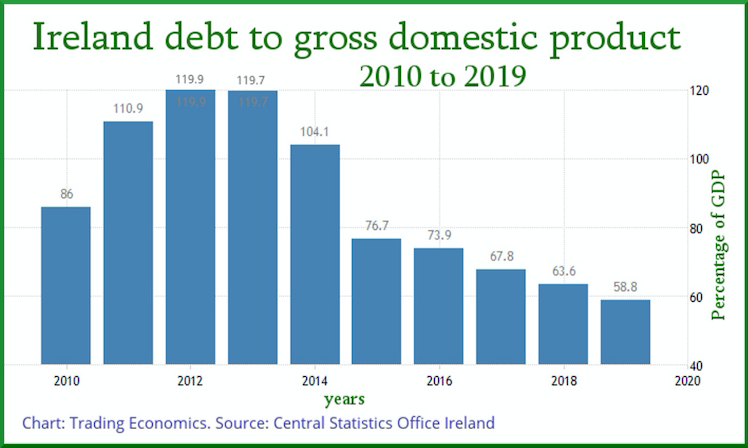

Ireland increased its debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) through the GFC to 119.9% by 2013. Since then, through the recovery phase, it has reduced it to a manageable 58.8%.

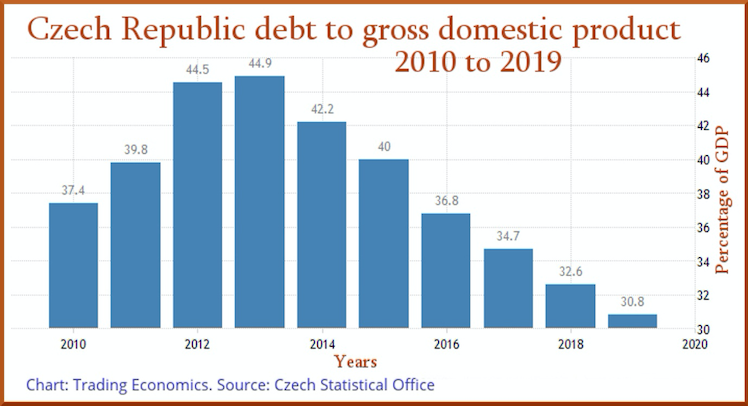

Similarly, the Czech Republic increased its debt to GDP through the GFC to 44.9% by 2013. It has now reduced it to 30.8%.

Other OECD economies with similar declining debt trajectories include these Euro Area countries: the Netherlands, Germany, Portugal, Austria, Belgium, Slovakia, Latvia, Slovenia and Lithuania. Plus these countries with their own currencies: Hungary, Denmark, Iceland, Israel, Poland, New Zealand and Sweden.

In stark contrast to these well-managed economies, Australia’s gross debt has continued to soar through the recovery period from 2013 to 2019.

Within the 36-member OECD, 23 countries have reduced government debt, ten of them by more than 10% of GDP. Only 13 have increased borrowings over this period, with Chile and Australia alone doing so by more than 10% of GDP. See green chart, below.

Australia’s gross debt has increased from 30.5% to 45.1%, an increment of 14.6. Chile is only marginally higher, rising from 12.7% to 27.9, up 15.2.

Notes:

(i) Most data is from Trading Economics, supplemented by updates from Statista, as required.

(ii) Four countries have not yet provided debt figures for 2019 — Canada, Japan, Mexico and South Korea. We can determine from 2019 budget figures that South Korea’s debt will likely have deepened, but the other three will not have changed significantly from 2018. We have adjusted South Korea’s debt by 0.5% of GDP accordingly.

New Australian debt records

Readers who experienced the 2008 global financial crisis will recall the furious anger with which the Coalition and virtually all the mainstream media attacked the Gillard Government when gross debt breached $150 billion in July 2010. The screams of outrage were even greater a year later when the debt hit $200 billion. That’s despite the fact that Australia’s debt back then was close to the lowest among developed countries.

Curiously, however, the media virtually ignored gross debt breaching both $300 billion in Tony Abbott’s first year and $400 billion in late 2015, shortly after Malcolm Turnbull had replaced Abbott. Deathly silence in mid-2017 when the debt exceeded $500 billion and barely a whisper when it smashed through $600 billion earlier this month.

Three points to note here. First, debt is not always intrinsically bad. Almost all economists now agree the debt Labor took on during the GFC was entirely appropriate. Second, Australia did not need to take on any further debt after 2013, as is shown by the experience of the rest of the developed world. And third, the recent debt blow-out in Australia occurred well before the coronavirus impacted the economy.

“the recent debt blow-out in Australia occurred

well before the coronavirus impacted the economy”

The Coalition’s legacy

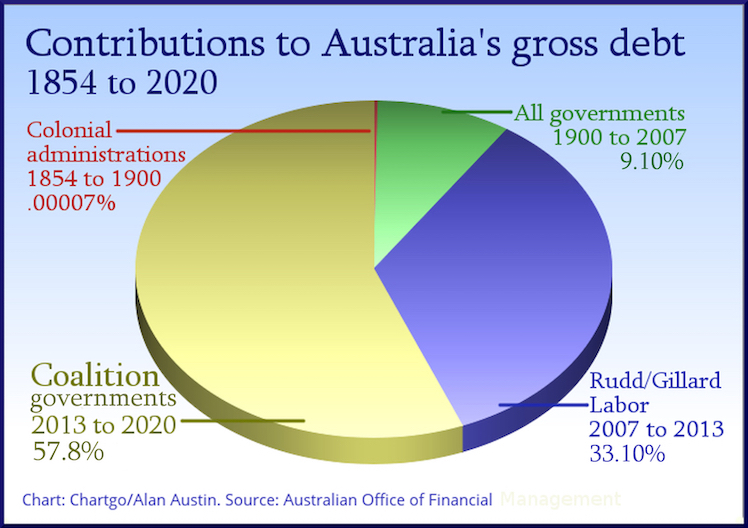

Applying the Coalition’s strategy of looking at ratios to GDP when it suits and raw dollars when more convenient, the pie chart, below, updates contributions to Australia’s total dollar debt — which first started to accumulate in 1854. The current Coalition is responsible for more than 57% of this — well over half.

Net debt also ballooning

When the Coalition took office in September 2013, Australia’s net debt – gross borrowings minus interest-bearing loans – was a modest $161.3 billion. That was matched, however, by the strong increase over the preceding five years in national assets, including school and community buildings, roads, railways, ports, building insulation, defence housing and other infrastructure.

Since then, net debt has risen above $430 billion — more than two and half times higher. But with no significant infrastructure or other benefit to show for it.

As has been shown elsewhere, the losses to Australia’s budget – and its citizens – as a result of the failure to retain a fair share of the exported wealth, continue year after year.

Factchecking Frydenberg’s gloss

On this topic, Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg continues to make assertions inconsistent with the evidence:

“Australia entered the coronavirus crisis from a position of economic strength. The Government returned the Budget to balance for the first time in 11 years, while government debt to GDP was about a quarter of what it is in the United States or United Kingdom, and about one seventh of what it was in Japan.”

Three problems here. Australia has not been a position of economic strength since the first Coalition budget in 2014. Since then, debt has deepened, the Aussie dollar has weakened, wages have been reduced in real terms, economic growth has fallen relative to comparable countries and the jobless rate has tumbled down the global rankings.

The budget has not been returned to balance. Yes, a promise was made in April 2019 that there would be a surplus by June 2020. But the late 2019 bushfires soon stymied that. The closest Australia got to surplus was the deficit of $9,669 million recorded in last August’s monthly finance statement. The latest statement, for March, has the deficit blown out to $22,359 million. Already. Before any coronavirus impacts.

Yes, debt to GDP is now 42% of the level in the USA and 19% of Japan’s level. But the Coalition and its mendacious enablers in the media cannot have it both ways. Back in 2010, Australia’s debt was only 22% of the US level and just 9.8% of Japan’s. If that was a “debt and deficit disaster” and “Labor’s debt timebomb” and “debt spiralling out of control” back then requiring the dismissal of the Labor Government, it cannot be justly claimed that all is well today.

Alan Austin’s defamation matter is nearly over. Readers are warmly urged to support the final crowd-funding push. The latest update is here; the GoFundMe page is here.

———————

Australia’s economic growth improves, but hold the champagne

Alan Austin is a freelance journalist with interests in news media, religious affairs and economic and social issues.