Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s ‘Made in Australia’ policy could be bad, good or great for Australia, depending on how it is implemented. Rex Patrick looks at the great model.

Not So Lucky

In 1964 Australian writer and social critic David Horne penned an oft quoted line “Australia is a lucky country, run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck.”

If he were writing his book today his words would probably be more like this: “Australia was a lucky country, run mainly by second-rate people who squandered its luck.”

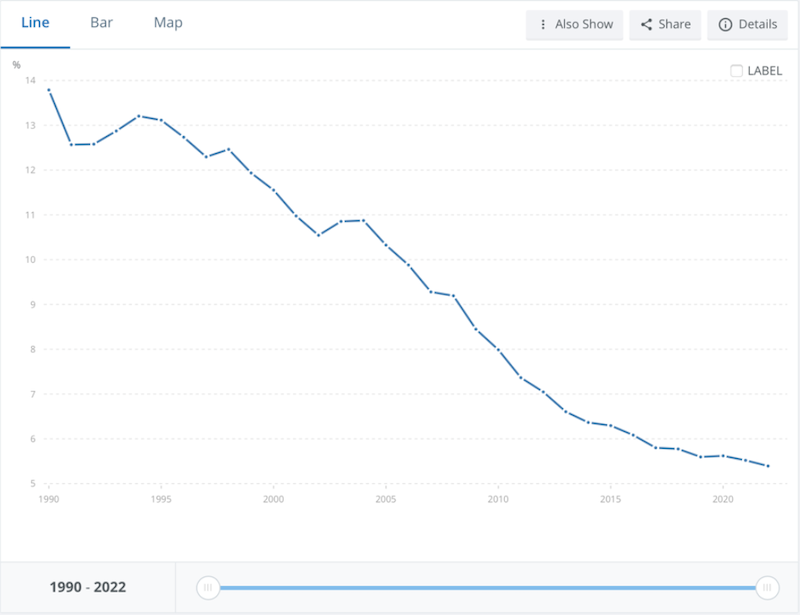

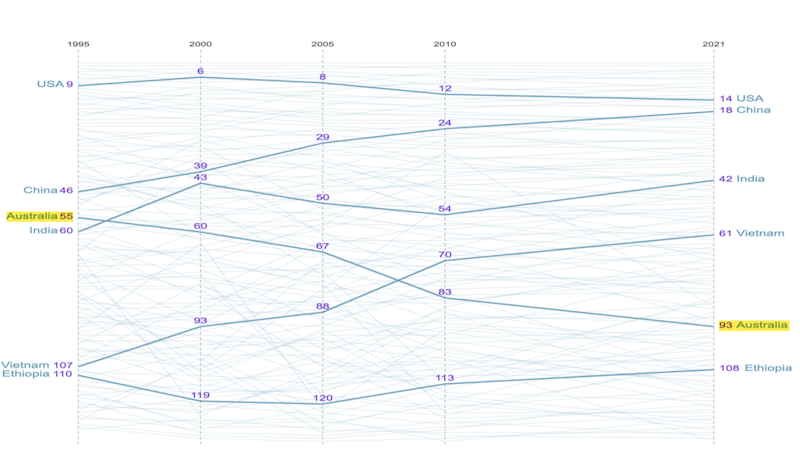

A couple of diagrams tell the sad story.

The first graph charts manufacturing as a % share of GDP. It’s shows Australia’s manufacturing base shrinking from 14% of our economy in 1990 to just 5.5% in 2022.

Manufacturing is a critical activity for a country. It’s where both white and blue collar workers are employed, it’s a key driver of innovation and thus a basis for the creation of intellectual property, it’s where the value-add occurs and it has a positive influence on balance of trade figures. It underpins national security, defence self-reliance and sovereignty.

The second graph, showing economic complexity tells a similarly sad story. Economic complexity is a measure of ranges of products that a country can export and normally correlates directly with the richness of a country. Wealthy countries generally have high economic complexity. Australia, which at 93rd lies between Uganda and Pakistan, is an outlier, rich but with low complexity, thanks to the great quantities of unprocessed ‘rocks’ we export to other countries.

This of course was part of the point Horne made decades ago. Australia has been riding on the back of minerals and energy exports for a very long time. Without changes to our manufacturing rate, the day oil and gas exports dry up will be the day Australia falls into a screaming heap.

Made in Australia

And that’s why Prime Minister Albanese’s ‘Made in Australia’ announcement is encouraging.

Of course, the policy brought out all the purists who revel in the theory of comparative advantage – the theory that a country should stick to doing the things it does well and at low cost and import those things which can be made more cheaply overseas (like face masks; or AdBlue; or refined fuels) avoiding the opportunity cost paid when doing it yourself.

It was no surprise the Chair of the Productivity Commission, Danielle Wood, came out against the policy (she wins points for exercising her independence speaking out against the Government) expressing productivity concerns. It’s true that Government’ subsiding an industry can lead to a “race to the bottom”.

But it’s also true to say that without doing anything, the two graphs will not change and we’ll see ourselves win a different race to the bottom.

Supporting industry must be done from a wide range of perspectives; jobs, employment stability, value-add, taxes, education, critical mass (the more in-country manufacturing there is the more likely local supply chains will develop and manufacturers will be able to leverage off manufacturers), national resilience and taxpayer return-on-investment.

The Right Stuff

And so what is the model that should be used?

One thing is for sure, we shouldn’t be asking politicians to just select winners. That’s a recipe for disaster. The policy needs to have comprehensive consideration. The following sets out the basis for a good model.

Resilience and Security

A first responsibility of the Federal Government is to ensure the nation is resilient to shock (like a pandemic or global financial turmoil) and secure from the influences of foreign government, including policy through to military coercion.

That means we need to determine what Australia’s critical industrial capabilities and the requisite capacities of them. The Government needs to determine industries that are:

- Highly Critical – mandatory capabilities (food production, certain, fuel refining, steel production, ship building/repair etc)

- Critical – supported capability where necessary (Energy generating equipment, certain pharmaceutical and medical equipment/supplies, rare earths processing etc)

- Of National Interest – desirable, but not critical (EV passenger vehicles, solar panels, semiconductors, etc)

This needs to be mapped out along with sovereign requirements – some capabilities and capacities will need to be nationalised or Australian controlled.

Procurement Support

It is not a matter of just handing a commercial entity taxpayer money through grants. Multiple approaches are required.

The first approach is through procurement.

The Australia Government must utilise its significant procurement budget to support Australian Industry, particularly those in the highly critical and critical categories. This will involve the rhetorical execution of the ‘free trade Taliban’ members lurking within the Liberal and Labor party parties, the Treasury, and the Department and Foreign Affairs and Trade. They need to abandon their utopic theories, open their eyes to what’s happening in the rest of world, and if they can’t cope, they need to move to some other theoretical sand pit to play in.

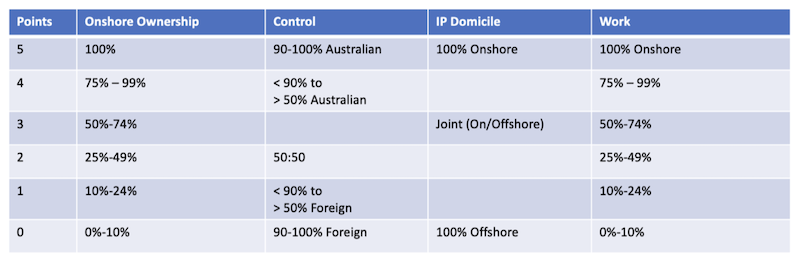

A statutory onshore industry rating system for suppliers should be adopted which can assist procurement decisions.

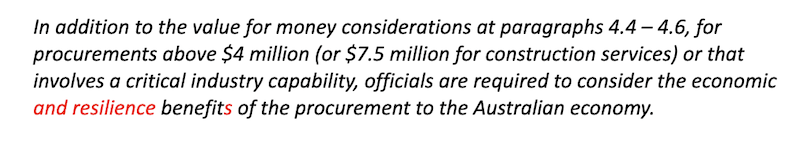

The Commonwealth Procurement Rules would need to be altered. Changes could be simple, as illustrated in red for s4.7 of the rules:

Economic Benefit, being jobs, capital investment, supply chain effects and tax receipts, would be Trade Agreement compliance. Resilience benefit would be Trade Agreement exempt.

Economic Benefit, being jobs, capital investment, supply chain effects and tax receipts, would be Trade Agreement compliance. Resilience benefit would be Trade Agreement exempt.

All major projects, including those of the Defence Department, would require an enforceable Australian Industry Participation Plan.

Smart Investment

The second approach is through Investment.

The first investment mode should always be an equity stake, which the company seeking funding support can buy back at a later date at some nominal profit to the taxpayers. Board room visibility is another advantage that could flow from this approach – where the Government board member ensures social licence (including responsible tax policies) expectations are met. A quid quo pro would be the company enjoying a positive government policy setting that supports their own investment.

Cheap loans are a second preference (recognising it does place Government in competition with the banking sector and so this needs to be carefully thought through).

Grants should be used for projects that deliver social benefits rather than commercial ones, so should be utilised very judiciously in a commercial sense.

Incentives to Australian based investment or superannuation fund managers which target local investment could be another policy lever.

Industry Capability Commissioner

An Australian Industry Capability Commissioner would need to be appointed to carry out industry rating, participate in and score tender evaluations, audit Government Agency procurements and assess delivery against Australian Industry Participation Plans, taking action against companies non-compliant with their Australian industry participation commitment.

This would need to be an independent statutory body, properly resourced to do the job.

Resource Commissioner

And while we’re at it, the Government should appoint a Resource Commissioner.

In the 46th Parliament the Senate did an inquiry into maximising the benefit of Australia’s oil and gas industry. The inquiry found that no-one in government has clear responsibility for ensuring Australia maximises the benefits from oil and gas (or resource) projects.

There are government entities responsible for identifying areas that potentially contain resources (Geoscience Australia), handling the titles and associated data (National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA)), safety (National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA)), the environment (NOPSEMA), taxation (Australian Taxation Office) and policy (Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER)).

But no identified player is responsible for ensuring that Australia maximises the benefits that flow from any project that seeks to extract and sell our oil and gas (or mineral) resources. Revelations that vast sums on money disappear into off-shore tax havens and foreign corporations barely pay tax are generally greeted in government corridors with the sound of crickets.

There’s a strong case for a resources supremo.

Leadership Required

‘Made in Australia’ could be an opportunity to fix those graphs, and fix Australia.

What’s been outlined above makes perfect sense which means it’s unlikely to make it through the Canberra bubble – certainly not without being significantly watered down.

Strong and effective leadership is required. That means this is an opportunity for Albanese too. The question is, does he have what it takes? I guess we’ll see, in due course.

Rex Patrick is a former Senator for South Australia and, earlier, a submariner in the armed forces. Best known as an anti-corruption and transparency crusader, Rex is also known as the "Transparency Warrior."