A light chuckle rippled through the audience at a breakfast event last Thursday morning in offices of McGrathNicol in Sydney’s Martin Place.

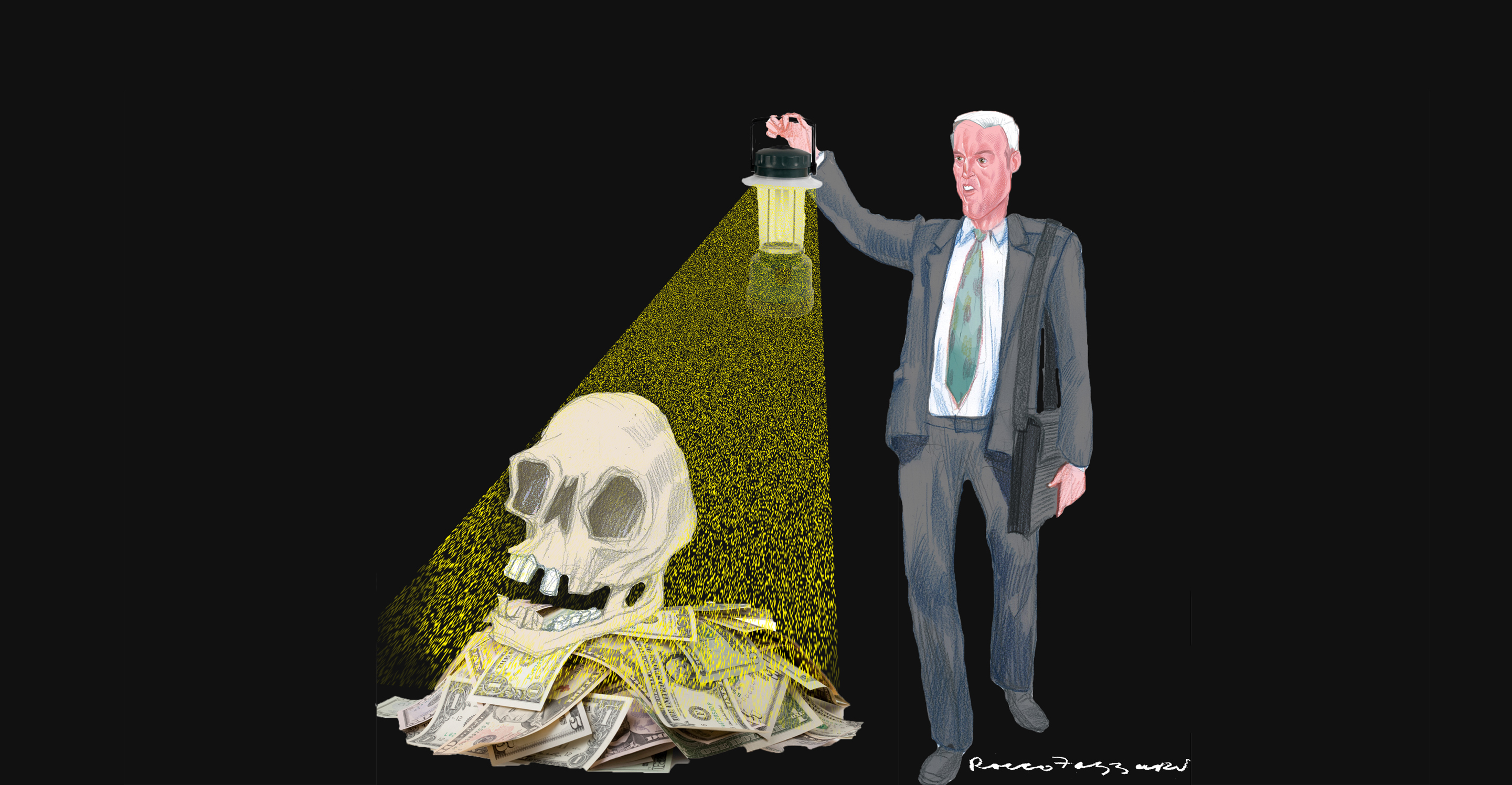

The cause for mirth was the suggestion that the worst punishment a company director could face in Australia, if busted for bribing a foreign official, was a ban from acting as a director ten years’ down the track. It was weary acknowledgement that white collar crime does pay, as few perpetrators are ever prosecuted and far fewer punished.

The breakfast, a symposium on foreign bribery held by McGrathNicol and law firm Piper Alderman, was held under the Chatham House Rule so we won’t delve into specifics. Suffice to say that, behind the scenes, lawyers are busy advising large companies on plenty of foreign bribery matters.

The decision however by Australian Securities Exchange chief Elmer Funke Kupper to stand down earlier this year amid bribery allegations was the exception rather than the rule. The rule is cover-ups and denial.

The most compelling message from the conference however was that Australia’s corruption laws are sadly inadequate and the US is therefore poised to reap billions of dollars in penalties and settlements at our expense.

According to Piper Alderman partner Ted Williams, It only takes one email through a US server, or one capital raising on a US bond market, to put an Australian company in the cross-hairs of the US Department of Justice. That pretty much encompasses most of Australia’s largest companies. We are not talking potentialities either.

“Bribery is a first-rate money spinner for the US”

BHP Billiton was pursued by the US Securities & Exchanges Commission for seven years over its hospitality arrangements at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. It settled last year for a civil penalty of $US25 million. That might sound like a pittance but there are surely more and bigger cases in the pipeline. This is a first-rate money spinner for the US.

Among its top enforcement actions, the US struck a $US800 million settlement with German company Siemens in 2008, $US772 million with Alstom (France) and $US679 million with KBR Halliburton in 2014. Eight out of the top ten enforcement actions were made with non-US companies, spurring France and the UK to tighten their laws.

In Australia though there has been only one successful prosecution. Ironically, two subsidiaries of the Reserve Bank, Securency and Note Printing JV pleaded guilty to allegations of making corrupt payments to foreign officials in order to win contracts.

Apart from that, there was a Senate inquiry into bribery last year and much in the way of worthy discussion on the subject but no legislative change as yet. There has not been one criminal prosecution of an Australian executive for foreign bribery; that despite a string of well publicised scandals engulfing Tabcorp, Leighton and AWB.

In the case of AWB there was no bribery prosecution despite a judicial inquiry finding AWB responsible for paying $200 million in kickbacks to the regime of Saddam Hussein in the “Oil for Food” imbroglio.

Had the regulatory failure around AWB not been so miserable, it is plausible that an offshore arm of Leighton Holdings might now not be facing allegations of corruption for paying millions in bribes to Iraqi middlemen to influence Iraq’s deputy prime minister, oil minister and other senior officials to deliver $1.3 billion in oilfield contracts. Prosecution constitutes deterrence.

“Being realistic, white collar crime does pay”

Ted Williams said last week Australia is “seriously exposed” due to the inadequacy of its foreign corruption laws. “The Americans are making a business opportunity out of their moral crusade”.

Although the US system of Deferred Prosecution Arrangements (DPAs) and Non Prosecution Arrangements (NPAs) under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act was not perfect, it was effective, he said. Under these arrangements, a corporation can avoid prosecution by paying the government a lump of money.

“Out of the uncertainty created by the Australian approach, US law enforcement agencies have stepped in, holding Australian companies accountable to US standards,” says Williams.

The moral hazards are significant, including that no executive perpetrators are ever charged and shareholders pick up the tab for corruption. These sort of deals are responsible for letting Wall Street fraudsters off the hook for the global financial crisis but, to be pragmatic, they work in an economic sense, putting business on notice for corruption and reaping billions for government.

Australia would do well to join this party. Being realistic, white collar crime does pay, if you are at the big end of town. A sea-change here in the lackadaisical culture of regulation is unlikely so the best government can do is to legislate for DPAs and bring in proper whistleblower protections.

“Whistleblowers are awarded 10 per cent to 30 per cent of fines”

Again, with whistleblowers, the US has a far more proactive approach, enticing them with a cut of the enforcement take. The SEC issued a $US30 million reward in September 2014, its largest ever, and since 2011 there has been more than $US85 million in rewards to 32 whistleblowers. The SEC does not reveal their identities.

Under the Dodd Frank Act (Whistleblower Bounties) 2010, they are awarded between 10 per cent and 30 per cent of fines.

According to Williams, the sectors most susceptible to foreign corruption are extractive industries and pharma due to their multinational nature, their necessity of dealing with foreign officials and third parties and the fact that bribery is rife in emerging nations.

In its submission to last year’s Senate inquiry, BHP advocated the introduction of DPAs and, further, that the “Facilitation Payment” defence (in business they call bribes anything from “chocolate” to “incentive payments” but never bribes) be removed. It also recommended beefing up whistleblower protections but stopped short of recommending they be paid.

Without dangling financial incentives however, whistleblowers are far less likely to come forward as doing so generally entails the end of their careers – hence bribery scandals are more likely to blow up via leaks to the press (as is the case with Leighton). The ensuing bad publicity undermines market confidence and stock value. It is messy for the company involved and, under the present laws, presents a red-hot target for lawyers and regulators in the US.

Michael West established Michael West Media in 2016 to focus on journalism of high public interest, particularly the rising power of corporations over democracy. West was formerly a journalist and editor with Fairfax newspapers, a columnist for News Corp and even, once, a stockbroker.