Peter Dutton’s plan to introduce a gas reservation scheme on the East Coast may be good politics, but industry experts say it is unlikely to lower domestic gas prices for a long time, if at all, Kim Wingerei reports.

A gas reservation scheme – forcing suppliers to set aside a certain amount for domestic use – is not a new idea. It was last floated by the LNP government in 2019, but nothing much came of it then.

It also remains unclear if the Commonwealth has the Constitutional power to unilaterally impose a domestic reservation scheme. It’s the states which preside over onshore drilling.

Labor has already hinted at a similar plan, and if recent examples of ‘policy matching’ are a guide, Albanese may just adopt Dutton’s suggestion.

Redacted. Gas lobby in lock-step with Government on “secret” gas reservation options

Dutton’s promise is to push down gas prices by diverting East Coast LNG spot exports into the domestic market. The Coalition also intends to ($) unlock ‘bucketloads’ of new gas by ensuring faster project approvals and through taxpayer investments in new gas infrastructure.

As is his wont, Dutton’s plan is low on details, particularly when it comes to how the reservation policy would work in practice.

According to gas analyst Josh Runciman of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), “Diverting LNG exports will, in the immediate term, undoubtedly put downward pressure on gas prices and help to ease cost-of-living pressures.”

The impact of faster gas approvals on gas prices in the short term is less certain.

Part of the plan is to accelerate gas project approvals. However, “accelerating approvals is highly unlikely to make a meaningful difference this decade,” says Runciman”

“This is because only a limited number of projects could actually benefit from faster approvals from the federal government, which has oversight of offshore gas developments. (Onshore gas approvals sit with the states and territories.)

The Coalition has already flagged its intention to fast-track ($) Woodside’s North West Shelf project, but this gas will be sold either into Western Australia or into export markets for liquefied natural gas (LNG), rather than to the east coast.”

“On the east coast, the Coalition’s policy is likely to target new developments in offshore Victoria. This makes sense given the proximity of these projects to major demand centres.

“Existing infrastructure also means they are likely to have a stronger business case than projects in remote basins that require new infrastructure, such as the North Bowen and Beetaloo basins. Investors may therefore be more prepared to back such projects given the lower asset-stranding risks.”

Empire building in the Beetaloo, funded by Federal Government gas grants

“The real question, however, is whether the Coalition’s policy will bring new Victorian gas projects to market quickly. Generally, it takes two to five years for a project to deliver gas once it has been issued a production licence, and potentially much longer for projects in the exploration and appraisal stage.”

That is to say, the Coalition’s policy may not lead to much new gas production in the next few years.

Domestic demand down

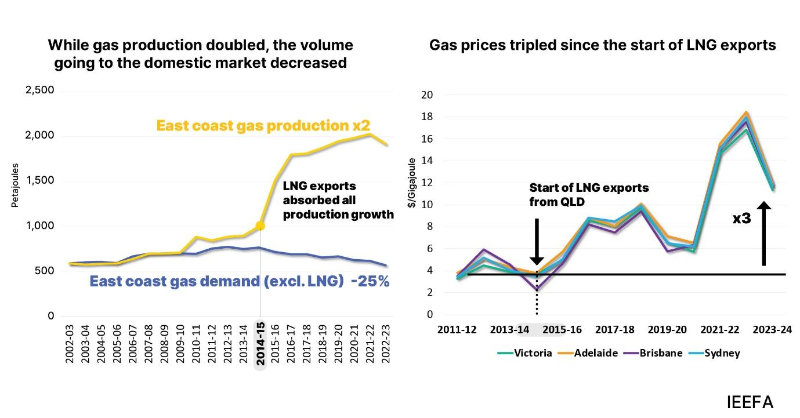

Runciman also points out that new gas production may not even be supplied to the domestic market in quantities that would drive down prices. In the decade since LNG exports from Queensland began, East Coast gas production has more than doubled. Over the same period, gas prices have tripled and non-LNG domestic gas consumption has fallen materially.

“The reason for this is that the LNG sector has soaked up all of this new gas supply (and then some) to maximise exports. Some of the Queensland LNG projects continue to export more gas than required to meet their long-term contracts, even as the LNG exporters have shifted from net contributors to the domestic market to net withdrawers.”

Sources: Australian government, Australian Energy Regulator (AER), IEEFA analysis.

Another issue is that bringing the gas to consumers requires infrastructure upgrades, which takes time, at least one or more election cycles.

Opportunity missed

The IEEFA points out that demand management may be a better option to bring prices down.

For example, Victorian households use substantial amounts of gas for space and hot water heating, and for cooking. However, rapid residential electrification, using more efficient electrical appliances, would slash gas demand while also reducing household energy bills.

IEEFA has also identified large untapped opportunities to deploy heat pumps in industry, in particular in the food and beverage sector, which is a large gas user in Victoria.

This could deliver large decreases in gas demand while only driving small increases in electricity use, and would reduce overall energy costs for businesses. There is a clear role for governments to do more to help households and industry make the switch away from gas.

Moreover, while Dutton’s plan is essentially aimed at increasing supply, the bottom line is that there is no shortage.

Mark Ogge of The Australian Institute: “There is no gas shortage and no need to approve new gas projects if exports are limited.”

Limiting exports is the only way to reverse this price increase.

Kim Wingerei is a businessman turned writer and commentator. He is passionate about free speech, human rights, democracy and the politics of change. Originally from Norway, Kim has lived in Australia for 30 years. Author of ‘Why Democracy is Broken – A Blueprint for Change’.