The hysteria about Labor’s proposed changes to the super tax for people with more than $3 million is driven largely by myths. Harry Chemay busts them all.

In recent years, the business media have made it only too clear that wealthy Australians have been using Self-Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSFs) to shelter ($) enormous amounts of wealth in these concessionally taxed vehicles.

Which is why the recent about-face, now railing on a near-daily basis against the Government’s solution, implementing a new tax on large balances, is so amusing. However, even some of the AFR’s commentators are starting to see reason ($).

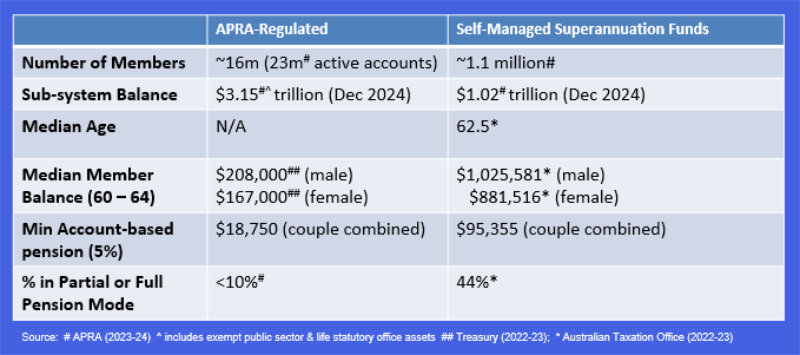

The superannuation system entered 2025 holding more than $4 trillion in wealth on behalf of some 17 million people. That amount is broadly in two camps, the so-called ‘APRA-regulated’ funds (so named after the system regulator and mostly open to all-comers) and SMSFs (regulated by the ATO), which each can have up to six members.

SMSFs were initially conceived to help the self-employed save for retirement, particularly those on the land (farmers and primary producers) and in the professions (barristers, medical specialists, dentists).

They have, however, morphed into highly tax-efficient vehicles for wealth creation since the mid-2000s, now used by more than one million people.

SMSFs account for only 6% of members but hold about 24% of all super wealth, more than $1 trillion in total.

At almost $2m, the typical SMSF near-retiree couple has about 5 times the retirement wealth of the APRA-regulated member couple. If converted into SMSF pensions, that would result in a starting annual tax-free income of almost $100,000.

If these pension balances rise into retirement, so does the tax-free pension income. Upon death, remaining balances can be passed on to dependents at generous concessional rates.

SMSFs are an effective way for high-income earners to move from the highest marginal tax rate (currently 45%) to 30% (super contribution tax rate for those earning more than $250,000), to 15% (current maximum rate of tax on super earnings) to 0% on the first $2m in retirement (i.e. up to $4m per retired couple).

Tax concession largesse

All these tax concessions don’t come for free. Someone must pay for them, and that would be the Australian taxpayer, with super contribution and earnings tax concessions expected to punch a $55B hole in tax receipts this financial year, according to Treasury.

Treasury estimates that during 2020/21, 83% of the super earnings tax concessions went to the top half of taxpayers, with 43% going to the top 10% alone. Men received 61% of these benefits, and overall 51% went to people aged 60 or older.

In 2005, fewer than 5,000 individuals had super balances greater than $3m. By 2017, it was 30,000, and today that number is estimated to be somewhere around 80,000 people. According to Treasury’s latest Intergenerational Report, if left unreformed,

the cost of total super tax concessions are on track to exceed the Age Pension during the 2040s,

Hence, the Government’s proposal is to tax the portion of super balances greater than $3m with a tax of 15% of any positive change in earnings during an income year. People are free to leave their $10m, $100m or even $500m ($) in SMSFs. It’s just that any earnings on amounts beyond $3m per member will face this new ‘Div 296’ 15% tax.

Now, onto those myths currently circulating about this new measure.

Myth #1: This is an ‘unprecedented’ tax on unrealised capital gains

The (admittedly somewhat inelegant) calculation of super earnings against which this Div 296 tax will be applied has some commentators crying foul, arguing that it would be an ‘unprecedented’ tax on unrealised capital gains. That, if true, would go against decades of tax convention and regulation.

In reality, it’s far from unprecedented, with APRA-regulated members in effect having estimated earnings tax (including estimates for realised & unrealised gains) applied to the daily unit prices for their options while accumulating super. That’s been standard practice for as long as I’ve been in super (nearly 30 years).

Also, don’t homeowners pay council rates that increase over time with land prices and so-called ‘capital improved value’? What is land tax if not a tax based on capital appreciation, i.e. an unrealised gain?

Myth #2: It will be a blow to productivity

Another line of attack is that this Div 296 tax will somehow impact economic productivity as older, high-income skilled workers are ‘forced’ to retire early rather than continue to build their super savings, leaving us all poorer for their departure.

I mean…I guess…maybe? To be fair, productivity growth has been in the doldrums for well over a decade (despite a temporary uplift during COVID).

But to suggest that older, wealthier, knowledge workers will unlace their boots and walk off the field due to this tax flies in the face of growing evidence that older workers, far from retiring, are staying involved in the workforce for longer.

Rest assured, those lucrative non-executive director positions are in no danger of going unfulfilled.

If we’re really concerned about falling productivity, there is a far more obvious issue worth targeting.

Housing affordability. The crisis the major parties are too scared to fix

Myth #3: It will drive investment away from the startup sector

Perhaps the most shrill criticism of the new tax is that it’ll make Australia ‘uninvestable’, by starving innovative startups of badly needed seed capital. The premise being that if we want more Aussie startup successes like Atlassian and Canva, we shouldn’t hobble their funding sources. Presumably, this refers to angel and early-stage investing by SMSFs.

So I reviewed the latest SMSF stats released by the ATO. Only 6.7% of all SMSFs had exposure to unlisted Australian shares (under which holdings in startups would be categorised) as at June 30, 2023.

Of all SMSF investments, unlisted Australian shares account for only 1.4% of typical holdings. And that’s across all unlisted entities, from a sole-founder startup to the aforementioned Canva, now estimated to be worth close to $50B.

I get why SMSFs might want to hold startup equity, because the returns can be astronomical and those gains can be sheltered from tax, but if it’s all the same, I’d prefer Australian taxpayers not to experience a Peter Thiel-like outcome.

Myth #4: Being unindexed, it will eventually capture everyday workers

I wish. Retiring on $3m would be nice, but the average employee is not going to come within a bull’s roar of it.

Not according to Treasury anyway, who undertook detailed modelling of superannuation balances back in 2019, forecasting them out to 2060. Their estimate would be for today’s median young Australian male accruing a super balance somewhere around $500,000 (in 2019 dollars) by then, with females accruing around 10% less.

That hasn’t stopped several parties claiming otherwise, with one forecasting average workers would retire with $3.6m after 40 years of work. Never mind that to make the numbers work, it had to assume uninterrupted employment and use a rate of return that hasn’t been consistently achieved since the introduction of the super guarantee over 32 years ago.

As someone who has built super projectors, I know that

if you torture the assumptions enough, they will confess to any balance you might wish to validate.

Using Treasury’s long-term assumptions for real wage growth and super returns, however, I estimate that it would take somewhere around 50 years for the median male 20-something employee today to build a super account of $3m if this proposal remains unindexed.

That said, the more pragmatic approach would be for the Government to index the $3m. After all, there used to be a concept of ‘enough’ in super. It was called the Pension Reasonable Benefit Limit (RBL), and it ceased to apply from 2007/08, when it was around $1.4m. Had it continued, it would be some $2.5m today.

So $3m is a decent uplift on the previous legislative notion of a ‘reasonable’ super balance at retirement, but it is equally reasonable that this Div 296 tax be indexed to wage growth the way RBLs were. If so done, I estimate that the limit would increase from the proposed $3m to around $13m in 40 years. That would ensure that this tax continues to apply only to the very wealthy by community standards.

The Government’s reticence might have something to do with putting the Div 296 revenue ‘forward estimates’ in their best light, but at some point this tax is going to have to be indexed.

Myth #5: People will flee super & put all their money elsewhere

Possibly some of the wealth, but certainly not all. The tax perks, even with the new tax in place, are simply too great for wealthier Australians.

I was an Adviser during 2006/07 when the floodgates opened on super, the then-Coalition government allowing a ‘one-off’ $1m of after-tax funds to be contributed per person (so $2m per wealthy couple) under its ‘Simpler Super’ reforms. In hindsight, that was the tipping point at which the superannuation system morphed from being a retirement system designed to support middle Australia into a wealth creation vehicle for the upper reaches of society.

I know this because much of my 2006/07 was spent getting money out of property, family trusts and private family companies into SMSFs for wealthy clients.

If the Div 296 tax is implemented, we may see a swing back to the pre-2007 days of wealthy Australians using family trusts and other low-taxed structures, in search of a better tax outcome.

Great, not a problem, because

superannuation was never meant to be an inexhaustible magic pudding for the ultra-wealthy.

Harry Chemay has more than two decades of experience across both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. An active participant within the wealth and superannuation space, Harry is a regular contributor to investment websites in Australia and overseas, writing on investing and financial planning.