Even those fleeing the Taliban, asylum seekers who helped our war effort in Afghanistan, face indefinite detention for another year. Lawyer and human rights advocate Alison Battisson reports on the victims of Australia’s detention regime and their fight for freedom.

It is two days before Christmas 2021. The Sydney CBD is largely empty as offices officially close and people are enjoying time with family and friends. The few people in the city avoid each other to ensure their Christmas celebrations are not impacted by COVID.

I am not at home, and I am not with family. Instead, I am sitting in the offices of a barrister finalising submissions and evidence for a hearing before the Federal Court of Australia. My clients, the applicants before the Federal Court of Australia, are also not at home with family. Instead, they are locked inside a hotel with tinted windows to ensure no one on the outside can see them, and with no access to fresh air. They are not, however, in quarantine due to COVID.

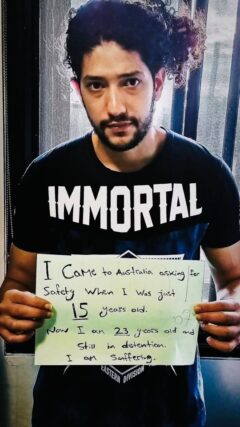

My clients are two cousins wo arrived in Australia as 15 year olds. They speak fluent English and are interested in music, art and poetry. They come from a family of lawyers and political activists. They use to play football, and would love to try AFL. Afterall, they are locked inside a hotel in Melbourne, the spiritual home of AFL.

Mehdi and Adnan are now 23 and 24 years old. As such, you would assume they have completed schooling, perhaps gone to university, had their first experience of love, perhaps had their hearts broken. They are good looking young men.

But Mehdi and Adnan have done none of these things. Instead, they have been moved around detention centres in Australia and on Nauru. Their education appears to be permanently on hold. They have had no chance to meet a first love in any setting than a detention centre or camp, where contact with visitors is officially limited to “one kiss on the cheek on arrival and departure”. No hugs allowed. No one has hugged these boys for years.

What Mehdi and Adnan have experienced however is exposure to self-harm, including self immolation of other refugees, and attempts themselves.

They have been attacked, and feel constantly scared, uneasy, at risk. Their mental health is understandably poor and their physical health is deteriorating as well. They were brought to Australia for medical treatment. Instead, they sit in their rooms everyday. Waiting.

Mehdi and Adnan live in the hotel with approximately 35 other refugees, including Sayed. Sayed worked with the allied forces in Afghanistan for over two years. He worked in a forward base at great personal risk. After being tracked down by the Taliban, he fled to Australia. He, as well, was sent to Nauru.

Sayed was recognised as a refugee, as are Mehdi and Adnan. And then Sayed waited to be permanently settled somewhere. And waited. He wanted his family to join him. They too were at risk from the Taliban due to his role in assisting the allies.

In 2019, Sayed couldn’t take waiting for permanent settlement any longer. He set himself on fire. He suffered burns to over 50% of his body. Sayed too was brought to Australia for medical treatment, and he too remains in the hotel.

I am advocating for Sayed as well. Doing interviews, writing to politicians in the hope that they too haven’t gone home for Christmas and forgotten about Sayed. About his support against the Taliban, his support for us, for democracy.

The Kabul Uplift

This is my day job. In August 2021, my day job was put on hold when the Taliban took over Kabul.

On 15 August 2021, while our politicians were telling us that Kabul would not fall quickly, I received a phone call from a friend. “Ali, the Taliban have just gone past our house. My family is running in front of them to get to the airport.”

Over the next ten days, I was involved with a “rag tag” group of volunteer lawyers and athletes to assist in the evacuation of people, including the Afghan women’s football team. I slept two hours a night, and submitted over 180 visa applications, while talking groups of people through Taliban check points. I told children to get into a crowded sewage. 110 people made it out.

And so it outrages me that Sayed, with his burns, remains detained. Sayed, who worked with our allies in Afghanistan. He may have been better off hiding for eight years and then trying to get to an airport.

I’ve also been involved in assisting people and their families in the legal community to get out of Afghanistan. People with children like Mehdi and Adnan, whose family members include lawyers.

As I contemplate their situation, I realise it is easier to help extract people from Kabul, with the Taliban and ISIS banging down the airport doors, than it is to get Sayed, Mehdi and Adnan released from an Australian detention hotel.

Australia has created a monster. The purpose of detention has been lost – that is, short term stays to check character, health and protection claims. Instead, we have an industrial detention complex which requires the continual expenditure of billions of dollars to feed security and health contracts. It has become an ends unto itself.

This Christmas, there is room at my house for Mehdi, Adnan and Sayed. There is room at the inn, in Australia. It appears, however, that the industrial detention complex must keep on being fed. And so they remain, detained. Waiting.

———————–

Postscript: as I write this, I get the following message “the building is on fire.” The boys and Sayed are evacuated. But not outside. They are kept in the building. In the building with the fire. Mehdi can’t breathe – he doesn’t know what is wrong. They are afraid.

Alison Battisson is founder of Human Rights for All. Before establishing HR4A, Alison worked as a corporate lawyer for top tier firms in Australia, the UK and Indonesia. She has also worked with various volunteer organisations in Zimbabwe, Australia and the UK.