Michael West Media has learned that early results of a survey issued by the National Tertiary Education Union to its members show that the practice is effectively universal in the sector.

Alison Barnes, National President of the National Tertiary Education Union told Michael West Media.

“We have always known it was going on but because of the casual and insecure nature of employment – that precarity works against reporting of underpayment.”

So far, least 10 Australian universities have admitted to underpaying casual staff, having to audit payments to staff or to being in industrial disputes with staff.

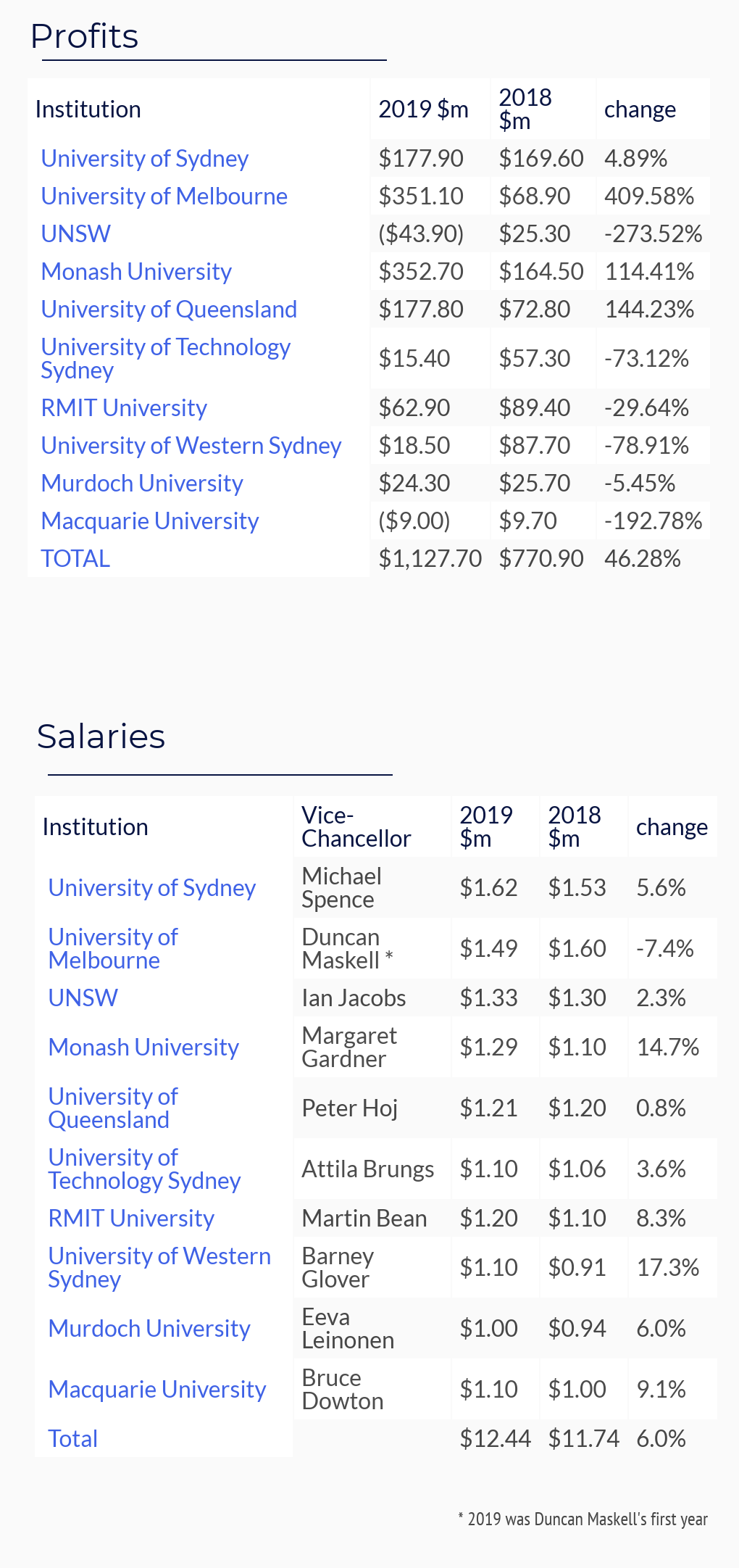

The 10 universities also collectively posted $1.12 billion in profits for the 2019 calendar year, a 46% rise compared with 2018.

Last week, the ABC revealed the widespread underpayment of casual staff across the public university sector, a practice unions describe as wage theft.

Teaching staff are already highly vulnerable, with the number of casually employed academics estimated at 70% of teaching staff in some universities. Moreover they are not eligible for JobKeeper due to rules that require more than 12 months continuous employment with an organisation.

It is unclear how many casual staff have been let go by universities although numbers are likely well into the thousands, especially as universities have also announced swingeing jobs cuts due to the pandemic with thousands more to come.

“There is no requirement for university to report how many causal staff they employ,” Barnes said. The union is undertaking audits to try to understand the extent of the problem.

She accused the federal government of abandoning staff by stripping $10 billion from universities in the past decade.

They are also being abandoned by their vice chancellors, who earned salaries of at least $1 million in 2019, with all but one receiving pay rises.

Meanwhile, Australian vice-chancellors are also the highest paid in the world, with Sydney University’s Michael Spence topping the list at $1.6 million. While the argument regularly trotted out is that to attract the best you need to pay commensurately, it is worth noting that Spence is taking a pay cut of more than 50% in his new job as vice chancellor of the UK’s elite University College London. UCL ranked 15th in the world on The Times Higher Education rankings this year, 45 places higher than Sydney University.

Profits on the rise…

Monash University topped the list by banking a profit of $352 million (up 114%), with the University of Melbourne close behind at $351 million, up more than 400%. Sydney University’s $172 million profit was up 6%, and the University of Queensland’s $177.8 million was up 144%. All four are members of the elite Group of Eight or “sandstone” universities, the most popular destinations for Chinese students, who comprise more than one-third of Australia’s international student cohort.

Meanwhile, universities in the next tier were already beginning to struggle even before the devastation wreaked by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has now well and truly discredited the business model.

RMIT University’s profits dipped 29% to $62 million from 2018, University of Technology Sydney’s profit fell 73% to $15.4 million, University of Western Sydney eked out a profit of $18.5 million, down 79%, while Murdoch University’s profits edged down 5% to $24.3 million.

Two universities posted small losses: Macquarie University ($9 million) and the sandstone University of NSW ($43 million), a sharp reversal from its $25 million profit the previous

… but as charities they are not taxed

The profits of public universities, largely off the back of the boom in international students, are not taxed because these institutions are deemed charities despite becoming highly commercialised, as evidenced by the private sector salaries paid to senior staff and the high degree of casualisation.

But falling profits or even losses has had no effect on the salaries of the vice chancellors. The pay hikes averaged 6%, with other senior “executives” also getting significant pay rises. Meanwhile, workers in general have experienced a minimum five-year period of stagnating wages.

Yet pay hikes for university bosses and their senior staff continue unabated. The 2019 pay rises followed similar pay rises in 2018 as detailed in a previous investigation by Michaelwest.com.au. The pay rises were also booked before student numbers and profits were smashed by the pandemic.

The peak body, Universities Australia, estimates that losses across the sector will be between $3.1 and $4.8 billion this year alone. It appears the universities didn’t envisage even a slowing of the rivers of gold because until January senior management were busy writing themselves big salary cheques even as they underpaid casual staff.

Overpaid university bosses cry poor as their foreign-student riches evaporate

Duncan Maskell, the new vice chancellor of the University of Melbourne Uni, is being paid $1.49 million, which is lower than the $1.6 million his predecessor Glyn Davis was paid in his final year in 2018.

University of Sydney vice chancellor Michael Spence, who is in his final full year, was the highest paid with $1.6 million, up almost 6%.

The biggest pay rises went to the University of Western Sydney’s Barney Glover, whose salary jumped 17.4% to $1.1 million, while Monash University’s Margaret Gardner’s pay jumped 14.7% to $1.29 million.

Ian Jacobs from the loss-making UNSW was the third highest paid of the group with a salary of up to $1.33 million, up more than 2% despite his institution’s hefty loss.

(University financial reports list the pay of its senior executives in salary bands; only Sydney University explicitly details the salary of its vice chancellor.)

At all 10 universities that have been identified for underpaying or likely underpaying staff, between four and nine senior staff, including the VC, were on salaries of more than $500,000. The general trend saw most executives jump at least one pay band between 2018 and 2019. Melbourne Uni topped this list with nine staff members paid more than $500,000; while UNSW and UQ each have eight staff earning more than $500,000.

Michael Sainsbury is a former China correspondent who has lived and worked across North, Southeast and South Asia for 11 years. Now based in regional Australia, he has more than 25 years’ experience writing about business, politics and human rights in Australia and the Indo-Pacific. He has worked for News Corp, Fairfax, Nikkei and a range of independent media outlets and has won multiple awards in Australia and Asia for his reporting. He is a fierce believer in the importance of independent media.