A cool $8 million for a bunch of chairs? A lazy $3 billion of taxpayers’ finest being forked out to some accountants? For advice? What, exactly, are “strategic planning consultation services”? How are politicians and the public service spending our money? In the wake of weekend revelations in The Saturday Paper about Scott Morrison’s disclosure issues while heading up Tourism Australia, “Triskele” investigates AusTender.

ACCORDING TO data from the Australian government’s contract procurement site AusTender, between 14 June 2007 and 18 May 2018, seventeen Commonwealth departments dropped a cool $8,447,090.84 on office furniture with one supplier alone — Gregory Commercial Furniture.

That’s a lot of bums on seats.

Gregory Commercial Furniture (GCF) is a Queensland-based company which touts itself as the preferred supplier to the Queensland government, and is also a NSW government approved supplier. Prices for furniture are not published on the website, but it is good to know there is an emphasis on ergonomics in their product range.

This writer is not suggesting that there is anything untoward about this company. The central issue is about the transparency of reporting of government procurement and contracting processes.

Gregory Commercial Furniture is not the only supplier to the Commonwealth departments in question, and the issue is much bigger than whether too many civil servants are sneaking in too many snoozles in their plush chairs.

The purpose of Austender is transparency … but

AusTender is the Commonwealth government’s business, contract, and procurement tracking system. Details of contracts awarded with a value of $10,000 or more are published here, as well as open tenders and approaches to market, which are required over certain thresholds.

This allows vendors to track government procurement opportunities and bid for them, and offers the public some transparency over where government money is spent.

In December last year, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) published the Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting Report, which highlighted inaccurate contract reporting and other potentially very serious inconsistencies in the reporting of governmental procurement contracts.

The issue raised alarm amongst MPs, and the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audits (JCPAA) called an enquiry into the tender reporting system, commencing in January 2018. One of the many issues to emerge from the ANAO and the parliamentary enquiry is the cloudy and inconsistent use of service category tags or contract descriptors. One of the principal beneficiaries of the use of vague or very general contract descriptors has been the Big Four accounting and consultancy firms – Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PwC – who, according to the ANAO, have collected a cool $3.1 billion over five years in ill-defined consultancy work.

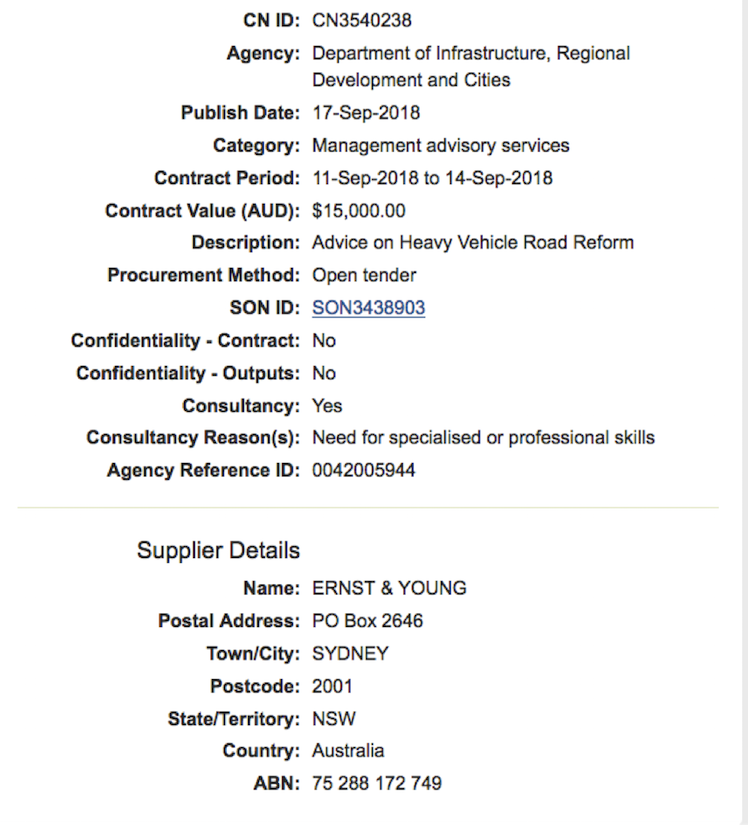

The service category descriptors most under a cloud for their vagueness are the tags “management advisory services”, “strategic planning consultation services”, “information technology consultation services”, “research programs”, “business intelligence and consulting services”, and “economic or financial evaluation of projects”. The use of vague descriptors has been critiqued in many submissions to the JCPAA as being a likely means of masking over the increase in private consultancy work, and in effect the outsourcing of what the general public might reasonably consider to be in-house, public service work. The work the public service is actually there for. In contract note CN3540238, for example, the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities has published a contract note under the tag “management advisory services”, awarded to Ernst Young, for four days’ work to give advice to the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities on Heavy Vehicle Road Reform.

It is reassuring to know that if the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities can’t work out how to do Heavy Vehicle Reform, at least Ernst Young has our backs.

But the really Bad Boys of government spending, according to the ANAO report, and independent reporting based on AusTender data published here, are the Department of Defence. Defence has hit it out of the ballpark when it comes to the excessive use of consultancies; an explosion in spending; and in its questionable relationships with companies which benefit from Australian government contracts but manage to avoid paying tax in Australia.

But, back to the bums on seats. The use of offending vague descriptors that obfuscate and mislead rather than clarify is not limited to consultancies. Contracts reported on AusTender use the code-set established by the United Nations Standard Product Services Code. It is clear that this code-set is insufficient to provide an acceptable level of detail, and thus, transparency. For example, there seems to be a curious amount of government procurement tagged under the broad descriptors “furniture”, “office furniture”, and the most widespread descriptor of all, “furniture and furnishings”.

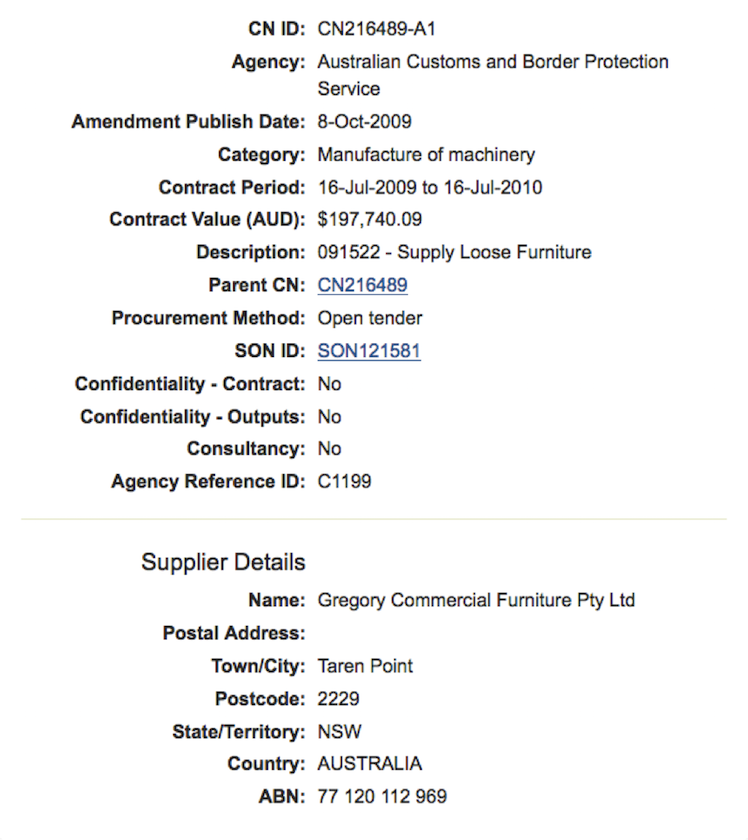

But good luck trying to find out how much was spent on these, where, and why. In some instances, purchases of furniture were classified with bizarre descriptors. In one puzzling example, a Department of Human Services purchase of tub chairs worth $12,029.49 from Gregory Commercial Furniture for a service centre at Mount Isa (CN597351) is tagged as “building construction and support and maintenance and repair services”. Likewise, a similar DHS contract with GCF (CN895601) uses the same tag to describe office fitout services at Bondi Junction. Other startling, even surreal uses of contract descriptors with Gregory Commercial Furniture include: an Australian Federal Police contract (CN53474) for office furniture, labelled “mining and oil and gas services”; a Department of Finance contract (CN182045-A1) for office chairs, but tagged “management and business professional and administrative services”; and this writer’s personal favourite: an Australian Customs and Border Force contract (CN216489-A1) for the supply of loose furniture, tagged “manufacture of machinery”.

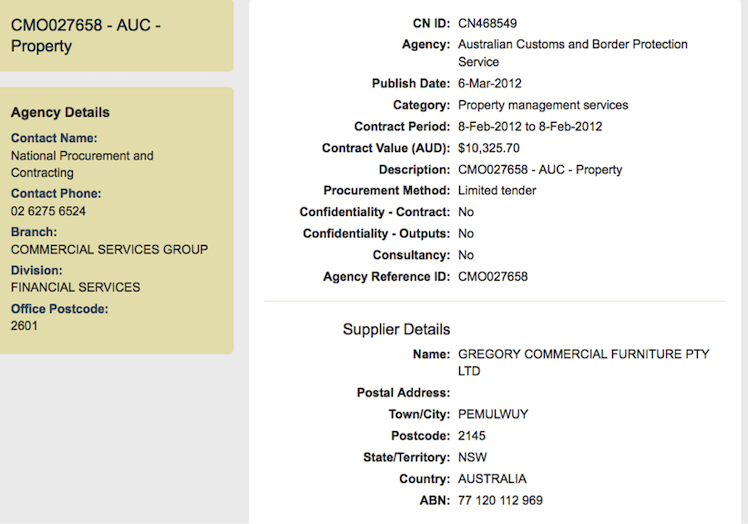

Another two curious contracts with GCF made by contracts Australian Customs and Border Force were both published on 15 November 2011 for exactly the same worth, and exactly the same one-day contract period, were both tagged “property management services” (contract numbers CN445350 and CN445351). It is impossible to know if this is a duplicate entry or if something else is going on. Yet another one day contract between Australian Customs and Border Force and GCF also applies the descriptor “property and property management” to a one day contract worth $10,325.70.

Perhaps they needed somewhere to store the machinery that day.

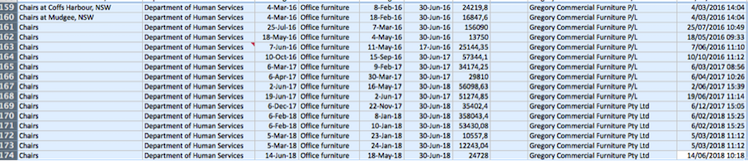

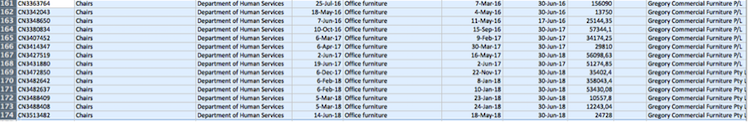

One might think that the Australian public service was already enjoying some pretty lax reporting standards on AusTender, and that contract category descriptors should be applied more meaningfully if any form of transparency is to be achieved. However, from about 2016, someone at the Department of Human Services seems to have reached the exact opposite conclusion, possibly having received the memo that contract descriptors for furniture were just too informative. Since about that date, all purchases of office furniture by the DHS are simply tagged as “chairs”. Not even the place where the “chairs” are destined for are now recorded.

Expenditures on “chairs” do not seem to be declining, even as the actual numbers of public servants decline due to caps on the public service, and the amount and value of outsourcing and external labour hire soars. Between 25 July 2016 and 14 June 2018, the DHS has published fourteen contracts for “chairs” with Gregory Commercial Furniture, with a total value of $918,090.9.

Granted, compared with the major league level of Defence expenditure blowouts, and the questionable places where that money is spent, it is reasonable to think that nitpicking expenditure on chairs is banal and petty (though it does allow for some enjoyable trolling). Yet it bears making the point that GCF is only one furniture supplier to the Commonwealth government departments, and there are many small contracts, as well as some quite large and some quite puzzling purchases published on AusTender.

Abysmal contract reporting may not be the only issue undermining the usefulness of AusTender. It may be that some contracts do not appear on AusTender at all, or that their descriptors are amended when placed under public scrutiny.

In an example of the first case, Karen Middleton has reported in The Saturday Paper that, ten years ago, an Auditor General’s report highlighted serious anomalies and problems with governance while Scott Morrison was managing director of Tourism Australia, a post from which he was sacked in 2006.

This excellent article finally sheds some light on why Scott Morrison was sacked from Tourism Australia and reports on a scathing auditor-general’s report completed 10 years ago, which has escaped public scrutiny until now,

Who the bloody hell are you? @ScottMorrisonMP #auspol https://t.co/8J4QQluVqV

— ?Peter Harden – Ghost Water Sales Rep (@hardenuppete) November 9, 2018

It is notable that the allegation is that information about large contracts was kept from the board and procurement guidelines were breached, and two major contracts were signed which never subsequently appeared on the AusTender site. There is also evidence to suggest that descriptors can be amended after publication, if contracts are being subjected to unwelcome public scrutiny. For example, it seems some contracts which were originally marked on AusTender as consultancies were subsequently edited after the ANAO report, in order to make consultancy contracts appear to be general contracts instead, thus helping to mask the explosion in consultancy contracts.

For its part, the Grattan Institute noted in its submission to the JPCAA that many of these contracts reclassified from consultancy to general contracts came from the Department of Defence. As Michael McKinley recently noted in an article entitled ‘Crony capitalism and corruption in our midst’, if one looks for corruption in Australia, one will not be disappointed. He observed:

“there are many rooms in the house of corruption….Vertically, the scale runs from the petty to the grand and systemic”.

Not because the scale is petty rather than scandalously egregious should we cease to look. Accountability and transparency are values taken for granted at our peril. The Department of Finance’s Government Procurement Rules include safeguards to ensure the public receives value for money. However, the Department of Finance said in its submission to the JCPAA that AusTender is not meant to be used as an expenditure reporting mechanism, and that individual Department Annual Reports should be consulted for the details of contract spending. The department also announced that it is prototyping a “Transparency Portal”, which is being trialled now, and will be fully rolled out in 2019, and which will “include tools to allow easy extraction of reports on Annual Report data”.

In the meantime, the APS continues to buy many chairs from Gregory Commercial Furniture (and its many other suppliers). Perhaps the APS workers really do need all that ergonomic support. Or, perhaps those of them that remain are just being disciplined –“Spanish Inquisition” style – with the comfy chairs. Fetch the Comfy Chair!

Government spending soars amid blow-out in no-tender contracts

————————

Editor’s Note:

We have published the above investigation anonymously at the author’s request. “Triskele’s” identity and bona fides are known to us. “Triskele”  is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

Defence spending keeps spiralling as embarrassed government blocks data

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. Triskele’s identity and bona fides are known to us. Triskele is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.