The government sat on a report into the retirement income system for four months because it was so politically sensitive and then released it on the day the Brereton report into potential war crimes in Afghanistan was released. Harry Chemay looks at what’s at stake in the debate around the rise in superannuation guarantee levy.

Having sat on the final report of Treasury’s Retirement Income Review (RIR) for some four months, the Morrison government chose a Friday to finally release it.

But not just any Friday. It chose a day where the media attention would be strained to breaking point by the Brereton report into alleged atrocities and potential war crimes by members of Australia’s elite SAS in Afghanistan.

And the reason for the reluctance to give the final report clean air was because one issue was hyper-politically charged – whether the rate of the super guarantee (SG) should rise to 10% from 9.5% on 1 July next year as legislated.

A small but influential group of Coalition MP have been calling for a pause in the increase, arguing that in a COVID-battered economy, workers need more take-home pay to spend today, not more retirement savings to spend potentially decades from now.

That’s the theoretical argument for pausing SG, but as the saying goes, ‘In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice they are not.’ And that’s because this argument relies on businesses directing that foregone super into higher wages.

The case against raising the super guarantee

There has been a long-running debate among economists as to whether a higher SG does cannibalise wages and take home pay.

Some hardliners continue to argue that the super levy operates independently of wage growth, but evidence is growing that raising SG does indeed crimp wage growth more than might otherwise be the case.

Perhaps the most robust evidence comes from a research paper the Grattan Institute released in February this year. The paper reviewed 80,000 federal workplace agreements executed between 1991 and 2018 and found that 70 – 80% of an increase in the superannuation guarantee was accompanied by lower wage rises, typically within two to three years of the agreement.

This dispels the notion that the SG is some sort of magic pudding without consequences for take-home pay.

Superannuation industry gravy train

It is also abundantly clear that one of the biggest beneficiaries of a rising SG would be the superannuation sector itself.

Some $100 billion in SG contributions cascade into the coffers of the super funds each year. The average Australian household now pays almost twice as much in superannuation fees as they do on electricity each year.

Such largesse is exorbitant in comparison to well-run systems around the world. The high fee retail super funds account for a large portion of the fees, although this will change as the big banks hasten their exit from superannuation. Regardless, much work needs to be done to improve the ‘value for money’ equation for working Australians.

Without that, superannuation may end up being as much a wealth transfer mechanism to the financial services sector as it is a vehicle for the future retirement security of the average Australian.

Snouts in the superannuation trough: turbo-charging Paul Keating’s legacy

Finally, as the report notes, not lifting the SG to 12% from its current 9.5% would in fact disadvantage high-income earners more than the average Australian. This is because those holding the most in super get the biggest tax breaks, with the system operating as a wealth accumulation tool.

The lower SG would mean that people retiring with smaller balances would receive a higher age pension in retirement. As the report noted: maintaining the SG rate would have “little impact on the total Government lifetime support the median earner receives”.

The case for raising the super guarantee

Three decades of the compulsory SG has undoubtedly added significantly to the economic resources, and financial resilience, of the average household.

Before 1992, workplace superannuation was a privilege reserved primarily for those in the public service and select corporate employees. The initial 3% rate, now at 9.5%, combined with decent real wage growth up until the 2008 global financial crisis, has seen total superannuation assets balloon from $140 billion to a current $2.9 trillion.

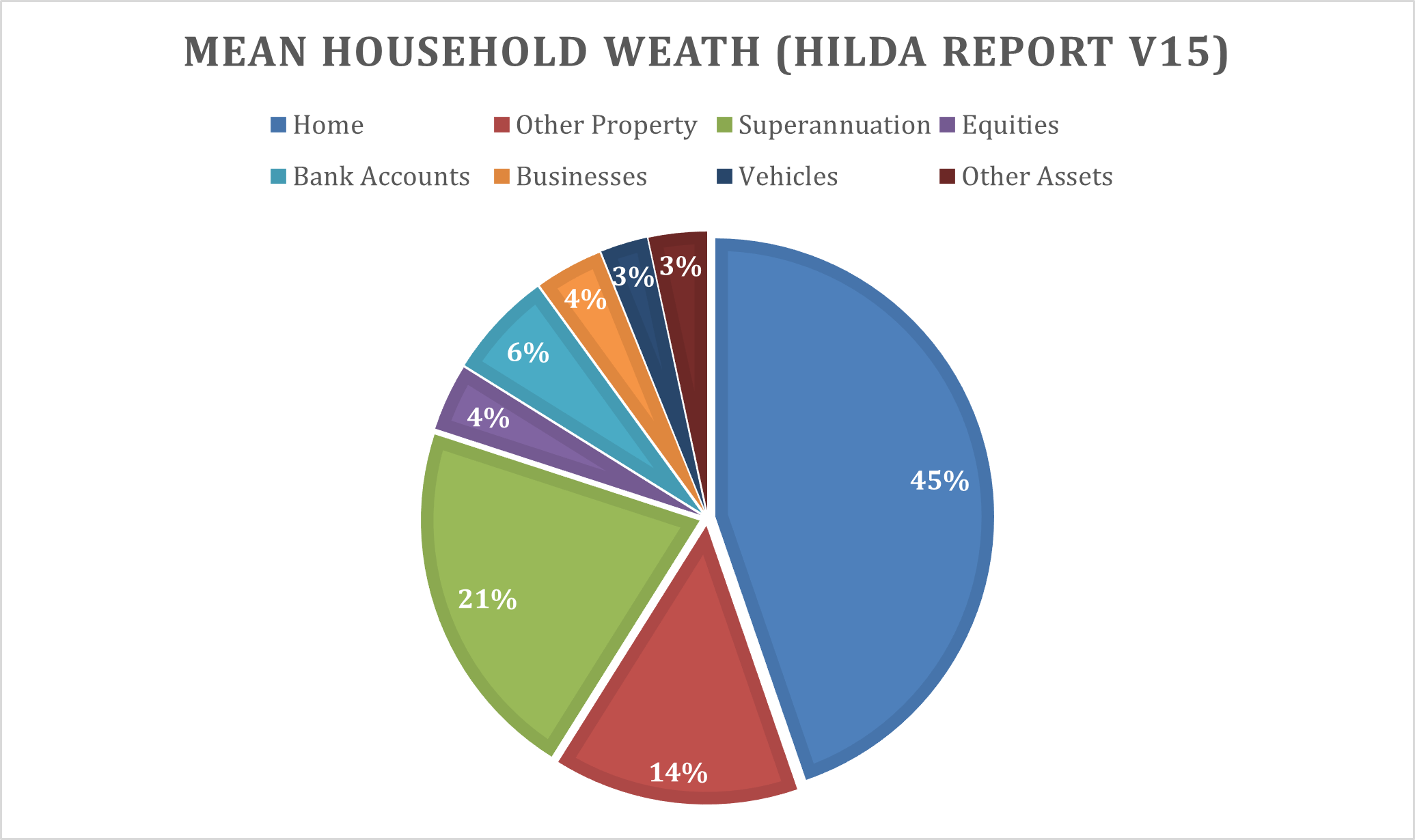

The latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey conducted by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research found that, as of 2018, the average value of super across surveyed households exceeded $240,000, constituting a fifth of mean household wealth, as depicted below.

Increasing the SG is likely to provide more protection for females, including a worrying growth in older women left in dire financial straits by late-life relationship breakdowns.

The final report acknowledges this, noting that “in absolute terms, asset-poor, single women outnumber asset-poor, single men, as there are a greater total number of single women in retirement.”

Pigs cleared for take-off

It is legislated that the rate of SG will rise to 10% on 1 July 2021, and again rise to 12% by 1 July 2025. The only way that can change is if the bill amending the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992. were to pass. That would require some deft negotiation by the Coalition to get the crossbench on side, knowing full well Labor’s opposition to any change to the current arrangements.

The arguments are so finely balanced, the government could conceivably cobble together the numbers, were it inclined to hit the pause button on SG. The business community would certainly welcome the news.

While the ‘higher take home pay now, not super’ argument holds a lot of appeal at present, it runs headlong into unequivocal evidence to the contrary.

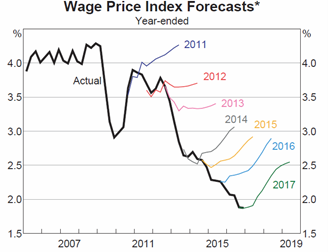

The RBA and Treasury have been forecasting rising wage growth, continuously and incorrectly, for the better part of a decade. It’s now at the point where the following RBA chart has become a parody of itself:

Source: Reserve bank of Australia

Bargaining power non-existent

If there was little sign of real wage growth before COVID ravaged the economy, reducing worker bargaining power with it, there’s precious little chance the situation will improve in the near future.

Fewer Australians are now covered by awards stipulating wage increases as compared to the last recession. Thus, there is every chance that a pause in the SG rate will simply result in the continued slide of the share of national income captured by employees, compared to employers as profits.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics confirmed this disparity in their most recent release of the share of Gross National Income which, as the chart below depicts, clearly shows the share captured by labour income flat to trending down, while capital income (profit share) has grown strongly.

Capital rewarded

In a nutshell, capital has been rewarded much more handsomely than labour over the past three decades, and there doesn’t appear to be any reversal in that trend on the horizon.

The currently legislated SG rate rise is the closest thing a growing number of Australians outside the award and minimum wage systems have to certainty of their total employment compensation rising, at least until 1 July 2025.

Absent a wages equivalent of the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act for all employees, pausing SG on the assumption that employers will voluntarily direct a greater share of their business proceeds to lifting wages would be the quintessential triumph of hope over experience.

Westpac and its super arm BT gouge $8 billion from unsuspecting public

Harry Chemay has more than two decades of experience across both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. An active participant within the wealth and superannuation space, Harry is a regular contributor to investment websites in Australia and overseas, writing on investing and financial planning.