While many deplore kowtowing to Beijing, or catastrophise about Premier Xi’s ambitions, Anthony Albanese’s trip to China is more than a symbolic reboot. Michael Sainsbury reports.

Hawkish columnists, security hardliners, and many senior Coalition leaders view every handshake with a Chinese official as appeasement. They’re missing the pandas for the bamboo forest, missing the need for a geopolitical hedge against a world sliding into Trumpian chaos.

PM Anthony Albanese appears to pursue economic as well as careful strategic engagement with China, Japan, South Korea and Southeast Asia. This is how Australia will survive in the next round of global disorder, and the Europeans are on the same page, too.

Economics Professor James Laurenceson, who runs the Australia China Relations Institute at the University of Technology, Sydney, told MWM, “The idea that Australia and China have big differences is hardly revelatory, right? That’s been true since 1972, of course, China’s more powerful now, I get it, right? But, you know,

managing differences in itself shouldn’t cause the Australia China relationship to go into a state of panic.

In today’s world, it’s not China playing games with trade, it’s Washington. US President Donald Trump is now promising to deliver – again and again and again – more tariffs, yet he is only creating more instability. It’s Xi Jinping, not Donald Trump, who holds more practical influence over Australia’s economic security.

Biggest trading partner

After all, China remains by far Australia’s biggest trading partner. It is the world’s largest industrial market and the primary destination for the volumes of iron ore and metallurgical coal used to produce steel in the quantities we extract.

China accounts for about 32.5% of Australia’s total exports, worth approximately $219 billion in 2023, with iron ore alone making up nearly half that value. Major Australian exports to China also include thermal coal, natural gas, gold, and services such as education and tourism.

On the import side, Australia purchased roughly US$107.5 billion in Chinese goods in 2024, making up almost 19% of its total imports. By contrast, Japan is Australia’s second-largest export destination, taking about 12% of total exports, while the United States is our second-largest source of imports at around 15%.

Despite recent trade tensions, China’s economic relationship with Australia dwarfs all others, underlining its centrality to the nation’s export earnings and resource sector.

If China were to suddenly disappear or ban all our exports, the Australian economy would collapse.

“The reset of the relationship with China after the chaos of the Morrison years is the major foreign policy achievement of Albanese’s first term,” Professor James Curran, Professor of History at the University of Sydney, told MWM.

Negative commentary

Both Curran and Laurenceson have been disturbed by the ”negative energy” of the commentary around the trip.

“You would think the sky was about to fall in,” Curran said, noting hysterical commentary from the usual suspects at News Corp and others. Laurenceson noted, “The Australian public is not on board with that sort of commentary. That’s not where the Australian public is at these days.”

That’s something that Coalition defence spokesman, the hapless Angus Taylor, has not yet noticed.

One of the reasons for this is that the trip is more comprehensive than any in the past decade. As such, both Curran and Laurenceson view this as a welcome return to a time when Australia was more engaged, and therefore informed, with China and Asia more generally, with three stops: Shanghai, Beijing, and Chengdu in the populous, sprawling southwestern province of Sichuan.

When this writer was a correspondent in China, extended trips by both Prime Ministers and a raft of other senior Cabinet Ministers were the norm. In April 2013, Julia Gillard’s second trip took in the Boao Forum in Hainan, Shanghai and Beijing with four Cabinet ministers in tow. Cabinet ministers would regularly visit Beijing and or Shanghai and then be taken to at least one other province; the idea was that they could at least get a glimpse of China outside the main cities.

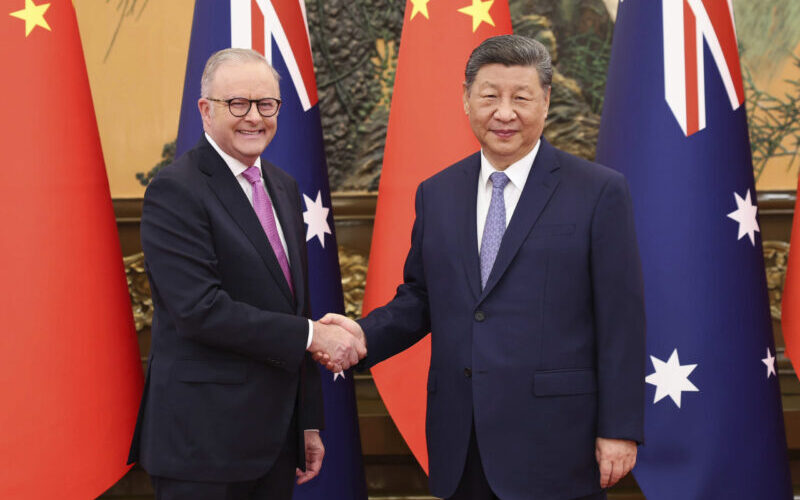

Albanese meets Xi

Albanese met Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Beijing on Tuesday, which happens to be before he met with the US President, just like Tony Abbott before him in 2013. And contrary to some of the mainstream media headlines, the world did not melt down.

In fact, it was remarkable in its normalcy. Albanese duly raised some points of contention, including the horrific imprisonment of Chinese-Australian writer Yang Henjun and China’s recent live fire exercises off the Australian coast.

“I raised the case. You wouldn’t expect there to be an immediate outcome, and that is not the way things work. The way it works is by that patient, calibrated advocacy, what Australians do, what my government does,” Albanese said.

The visit flips the hoary Canberra-Beijing narrative. Rather than obsessing over whether Australia looks “weak” amid a “failure” to get a meeting with the volatile Trump, re-engaging with Beijing is a pragmatic and necessary act of national insurance.

As the US turns inward and unpredictable, Australia needs well-functioning relationships with all major Asian powers, not just for trade, but for regional stability.

Strategic reset?

In a surprise speech setting the stage for his second term’s foreign policy ahead of the visit, Albanese invoked wartime leader John Curtin to assert Australia’s strategic autonomy, declaring that the country will “act in its own interests” amid global tensions.

He reaffirmed the U.S. alliance is a “pillar” of national security, but stressed it isn’t “the extent of it.” Pointing to pressures from the Trump administration—tariffs and defence-spending demands—he emphasised that Australia is “not shackled to the past,”

shaping foreign policy anchored in strategic reality, not bound by tradition.

“Curtin’s famous statement that Australia ‘looked to America’ was much more than the idea of trading one strategic guarantor for another… It was a recognition that Australia’s fate would be decided in our region.”

Curran believed that this could signal the careful beginning of a more independent foreign policy, “…they’ve been very careful, I think, to keep to that formula. And, you know, to cooperate, disagree where we must, all the rest. Yes, it is foreign policy by formula, but I think you know that kind of tightrope on which they’re walking now is being pulled from both ends because you’ve got Washington making demands that we cannot possibly adhere to on Taiwan.”

Even the vile human rights atrocities that the Chinese government is guilty of, which were recently very high on the list of reasons why not to engage with China, must be viewed against the Gaza genocide, as well as the horrific ongoing conflicts in nearby Myanmar and West Papua.

None of this means that Australia should let its guard down to China or any country that threatens the relative peace of the region.

China’s long-term desire to take control of Taiwan remains real and present. Albanese has correctly argued for the status quo. When asked if Taiwan arose during a meeting with Xi Albanese said “No”’ but that the Pacific was discussed in terms of “peace and security in the Pacific”.

Time will tell, but as Curran argues, “My view is that the primary role of Australian statecraft is to do everything we possibly can to avoid a conflict to avoid ever getting close to a decision about following the Americans into a war of that kind.”

As the so-called rules-based order collapses in real time, as those who set those rules toss them aside, this dose of realpolitik on display in China this week is one that has so often been missed in Australian diplomacy in recent decades. That in itself is a win.

Who’s next? Will Albo and Wong approve China attacking Taiwan?

Michael Sainsbury is a former China correspondent who has lived and worked across North, Southeast and South Asia for 11 years. Now based in regional Australia, he has more than 25 years’ experience writing about business, politics and human rights in Australia and the Indo-Pacific. He has worked for News Corp, Fairfax, Nikkei and a range of independent media outlets and has won multiple awards in Australia and Asia for his reporting. He is a fierce believer in the importance of independent media.