In the wake of the Bondi terrorist attack, and amid calls for a Royal Commission, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has commissioned an ‘independent’ review into federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Former senator Rex Patrick takes an unauthorised look at the “Richardson Review”.

The PM has appointed veteran Canberra insider Dennis Richardson to head up the inquiry into the Bondi attacks. Is the Richardson Review into the Bondi attacks really ‘independent’ and have some of its findings already been determined?

A domestic intelligence failure

David Tyler had it exactly right in his recent MWM analysis on the Australian Security Intelligence Agency’s (ASIO) failure over the Bondi Beach massacre.

Alleged perpetrator Naveed Akram, 24, had been investigated in 2019 by ASIO for his close ties to an ISIS cell in Sydney, including connections to Isaac El Matari, who identified himself as the head of Islamic State in Australia. The ASIO investigation ran for six months before Akram was cleared as presenting “no indication of any ongoing threat.”

Meanwhile, his father Sajid held a valid NSW firearms licence – a privilege extended to permanent residents, not merely citizens, and had legally acquired six long guns. The weapons sat in the family home at Bonnyrigg, in Sydney’s suburban west, where planning for mass murder apparently proceeded without detection.

What is the point of intelligence that can identify environmental protesters but cannot link a cache of guns to a known extremist connection? Tyler asked.

Tyler went on to reasonably declare that ASIO, which has been appropriated more and more public money each year (currently $700m per annum) with bi-partisan support but little regard to performance, had comprehensively failed.

An overseas intelligence failure

Taylor’s focus was ASIO, but it also is reasonable to ask what Australia’s external intelligence agencies – the Australia Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) and the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) – were doing as well.

ASIS’s functions, laid out in Section 6 of the Intelligence Services Act, include “obtaining, in accordance with the Australian Government’s requirements, intelligence about the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organisations outside Australia”. It’s an international spying agency; ASIS’s focus is on the world outside Australia’s borders.

ASD’s functions, laid out in Section 7 of the Intelligence Services Act, include obtaining intelligence about the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organisations outside Australia in the form of electromagnetic energy, whether guided or unguided or both, or in the form of electrical, magnetic or acoustic energy, for the purposes of meeting the requirements of the Government … for such intelligence.

Again, ASD is an international electronic eavesdropping agency; ASD eavesdrops on people outside Australia.

Spies like them

As a general rule, neither agency can spy on Australians when overseas. But there are exceptions to that rule, provided either the foreign minister (in the case of ASIS) or the defence minister (in the case of ASD) approves it. The ministers can only approve spying on Australians overseas for particular reasons listed in section 9 of the Intelligence Services Act. Those reasons include if a person is a risk the safety of any person or a threat to security.

Both father and son went to Davao on the island of Mindanao, Philippines, for almost a month just prior to the terrorist attack. It is a region from which several groups pledging allegiance to Islamic State operate.

On Tuesday the Prime Minister and the Australian Federal Police Commissioner revealed information received from the Philippines National Police after the Bondi attack to the effect that the Akrams spent most of their time at a local hotel and apparently did not did not undertake any training or “logistical preparation” for the attack while in the Philippines.

International connections?

That said Commissioner Krissy Barratt added “However, I want to be clear, I am not suggesting that they were there for tourism.”

All that begs some very serious questions.

Why did the Akram father and son go to the Philippines?

Who did they meet and for what purpose? If not for training, then was it for guidance, instruction or spiritual sanction for what they planned to do at Bondi?

Perhaps they were “lone wolves” as is now claimed by the Federal Government; but it’s also apparent they were in some way internationally networked.

And why has Australian law enforcement only learned about the Davao connection after the horror in Bondi?

Naveed Akram had been the subject of a terrorism related security inquiry. Surely his name would have been on a Border Force watch list, triggering an alert when he left the country bound for a known terrorism hot spot?

Were ASIS and ASD alerted?

ASIS and ASD could have been alerted. Perhaps they were. The Akram’s mobile phones could have been surveilled, geolocated, metadata analysed and potentially interception undertaken.

The AFP could have liaised with the Philippines National Police and ASIS could have engaged its long established networks in the Philippines.

So Prime Minister Albanese is right to initiate an inquiry into Australia’s federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

But has he chosen the right man for the job?

Will we get a cold hard report that demands accountability, or a soft report that simply calls for greater budget and greater powers – to be exercised in secrecy and without parliamentary oversight?

Richardson, distinguished career and a roving insider

78 year-old Dennis Richardson has had a distinguished public service career, serving as the Director General of ASIO from 1996 to 2005, then as the Australian Ambassador to the United States to 2010, then as Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to 2012 and then, finally, as Secretary of Defence to 2017.

One can reasonably say that Richardson is smart.

One can also reasonably say that he has pleased governments, both Labor and Coalition. He turned up to over 50 Senate Estimates sessions in his career, but in the halls of Parliament he was considered by many to have never really answered a question, certainly not a controversial one. He’s always had a highly-tuned sense of the direction the political wind is blowing in Canberra.

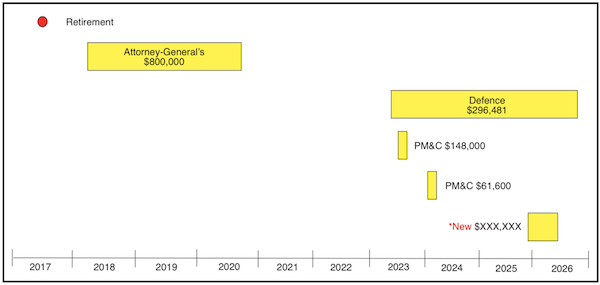

And since his retirement in May 2017, he’s never really left. He’s a roving insider that has fared well from the public teat in retirement with over $1.3M in sole sourced gigs.

These post-retirement gigs have included a comprehensive Review of the Legal Framework of the National Intelligence Community, a review of Integrity Concerns and Governance in Regional Processing Administration (Home Affairs) a review into the (non) Transfer of 2003 Cabinet Records and a review into the structure, governance, performance and direction of the Australian Submarine Agency.

It’s clear that Richardson has an ongoing attachment to the public teat that undermines any claim of full independence.

Marking his own homework

Richardson, because of his earlier role as Director-General and through his review of the National Intelligence Community’s framework is in some sense being asked to mark his own homework.

The terms of reference for the Bondi inquiry will look at, amongst other things:

- the interaction and information sharing between Commonwealth agencies, and between Commonwealth and state and territory agencies

- what additional measures, if any, should be taken by relevant Commonwealth agencies to prevent similar attacks occurring in the future.

- whether they have adequate legislative powers, the right systems, processes and procedures, and an appropriate authorising environment for information sharing with other federal and state and territory agencies

- whether warrant and data access regimes and powers are adequate

- whether any legislative amendments are required

Indeed, because of the legislative focus, one could also say Richardson will be redoing his homework.

Oversight shortfall

While Australia’s intelligence community has grown rapidly over the past two decades, the mechanisms of accountability and review overseeing those agencies have received much less attention, fewer resources and less authority.

In particular, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) has been tightly restricted under the Intelligence Services Act 2001 to review matters relating to the administration and expenditure of Australia’s intelligence agencies.

The PJCIS is explicitly prohibited from reviewing the operations of Australian intelligence agencies. The PJCIS is prohibited by the Intelligence Services Act 2001 from reviewing intelligence-gathering priorities and operations of Australian intelligence agencies, or the assessments and reports they produce.

The Committee is further barred from examining sources of information, operational activities and methods, or any operations that have been, are being or are proposed to be undertaken by intelligence and national security agencies.

Shirking Five Eyes

I spent much of the 46th and 47th Parliaments trying to bring Australia into line with our five eyes partners by subjecting the intelligence services to parliamentary oversight.

I was not the only person to introduce such legislation into the Parliament. Senator Penny Wong was the sponsor or the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Amendment Bill 2015 which did much the same as my Bill.

Wong never bought it to a vote and refused to support any of the many amendments I moved to intelligence related Bills that sought to force parliamentary oversight of intelligence operations. I conclude that Senator Wong and her National Security Committee colleagues have no conviction in such oversight.

Instead in November 2025, in a manifestly feeble response to the need for improved oversight and accountability, the Labor Government and Coalition Opposition agreed to legislation that allows the PJCIS to request the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security to undertake an inquiry into the “legality and propriety of particular operational activities” that they are still barred from examining themselves.

There’s nothing about oversight of priorities, performance or competence.

That’s all still off the table – or rather under the table.

So, meantime we’re left with a case of Caesar judging Caesar. The executive arm of government judges itself when it comes to intelligence matters – the Parliament has shirked its constitutional responsibility.

Richardson’s 2019 report’s recommended “The remit of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security should not be expanded to include direct oversight of operational activities, whether past or current.”

Don’t expect him to revisit that.

The intelligence services failed Australians in the lead up to the events that took place on December 14, 2025. We won’t see Richardson recommending the Parliament not take an active role in intelligence oversight.

Reward more money, more power?

What will come from this inquiry will be a soft report and recommendations for even more powers for our intelligence agencies to exercise behind black curtains, without parliamentary oversight.

The Parliament will be asked to expand the intelligence agencies significant powers with no effective oversight of those same agencies beyond the executive government – just as was the case when Richardson was Director-General and just as the senior echelons of departments and agencies, that from time-to-time pay Richardson to do work for them, would prefer.

And that’s the Prime Minister’s preference too. That’s why, once again, he’s picked Richardson as a “safe pair of hands” to do the work.

Rex Patrick is a former Senator for South Australia and, earlier, a submariner in the armed forces. Best known as an anti-corruption and transparency crusader, Rex is also known as the "Transparency Warrior."