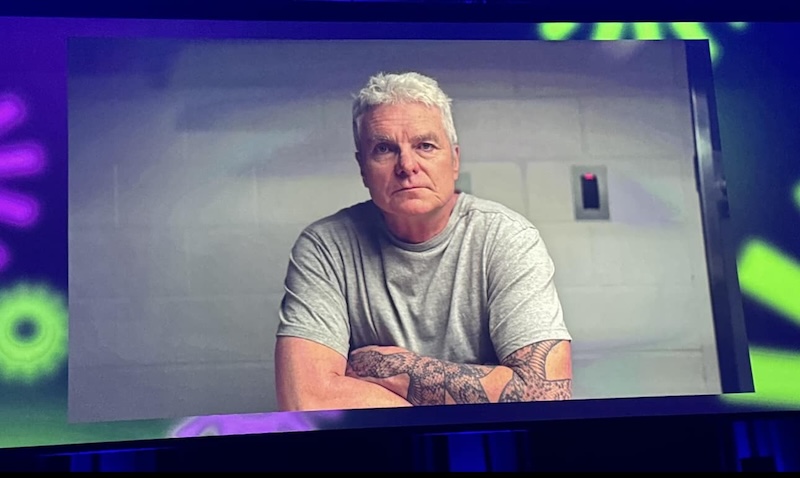

“Are there any circumstances where a soldier can lawfully disobey orders from their superior?” Stephanie Tran interviews Army lawyer and whistleblower David McBride from prison.

David McBride’s High Court appeal looms, and the highest court in the land will be compelled to rule on one of the most fundamental principles of law in a case that, if it proceeds, will have ramifications worldwide.

Speaking from Canberra’s Alexander Maconochie Centre, David McBride offers a quiet self-portrait: “I was someone who loved the Defence Force. Most whistleblowers have a deep commitment to the organisations they serve. We’re painted as being difficult and over the top. But we’re actually just people who like our job and take it seriously.”

McBride’s journey, from military lawyer to whistleblower to prisoner, has become emblematic of Australia’s uneasy relationship with truth-telling.

Once responsible for ensuring Australian soldiers follow the rules of war, he is now serving a sentence of five years and eight months, with a non-parole period of two years and three months, for leaking classified military documents to the ABC.

As the Human Rights Law Centre observed at the time, the first person imprisoned in relation to Australia’s war crimes in Afghanistan was not a war criminal, but the whistleblower.

Special leave application

On October 9, the High Court will decide whether McBride will be granted special leave to appeal his conviction. The outcome of the High Court appeal will reverberate far beyond McBride himself. It will shape the future of the Australian Defence Force and the conduct of our soldiers in future wars.

The question at the heart of the case is deceptively simple:

Are there any circumstances under which a soldier can lawfully disobey orders from their superior?

Under current Australian law, the answer is no.

McBride’s lawyers argue that this position “ignores Nuremberg”.

“There must be circumstances where a soldier can, and indeed must, disobey orders – even if those orders are authorised pursuant to military law,” McBride’s special leave application argues.

“The Nuremberg Tribunal recognised that following orders is no defence to actions that violate fundamental principles of law, such as crimes against humanity. The same principle should apply under Australian law: obedience to orders cannot excuse conduct that offends a soldier’s ultimate duty of service.”

The Nuremberg defence, formally rejected by the post-WWII Nuremberg Tribunal, held that individuals cannot escape criminal liability by claiming they were simply “following orders” when those orders violate fundamental principles of law. This doctrine became a cornerstone of modern international humanitarian law.

Yet Australian courts have inverted this [Nuremberg] principle.

Justice David Mossop ruled that the central duty of a military officer is to follow a “lawful order” and that this duty overrides any duty the soldier may have to act in the “public interest”.

It is this reasoning that McBride finds most troubling. “One of the things the government says about my case is ‘you only have to obey lawful orders’, but the orders to carry out the Holocaust were lawful under German law,” McBride tells me. “It’s maddening to think that the people in charge have forgotten these lessons.”

The disclosures

The public first encountered McBride through the Afghan Files, a series of stories published by the ABC in 2017 based on a trove of Defence documents McBride leaked. They detailed allegations of unlawful killings by special forces, later echoed in the Brereton inquiry.

But McBride insists the story was never just about Afghanistan.

“The idea that I was just about investigations in Afghanistan or covering up war crimes is ridiculous,” he says. “A third of the documents I gave to the ABC are not even about Afghanistan. They were about potentially illegal activities in Iraq … .”

They paint a picture of an organisation which is rotten from top to bottom

But when the ABC published the Afghan Files in 2017, McBride says they reduced his allegations regarding systemic rot within defence leadership to headlines about a few “bad apples.”

“Everything I gave the ABC, they managed to turn into some sensational headline, and there wasn’t a single criticism of the leadership.”

Failures in military leadership

For McBride, the failures in Afghanistan were never just about rogue soldiers. They were about failures in political and military leadership, where appearances were prioritised over accountability.

Investigations, he says, became a charade.

“They wanted to look like they cared about war crimes, so they investigated these non-entities who were innocent … The facts and the law didn’t matter. Appearances were everything. The senior leadership of the Defence Force were playing a complex media game.”

“If they really wanted to prosecute war crimes, they would use the drone footage evidence. It’s all recorded.”

He points to Ben Roberts-Smith’s first medal as an example: “When Roberts-Smith got his first medal, he had shot a shepherd boy, and they rewrote it as ‘Roberts-Smith bravely fighting an anti-coalition militia force’. This was a shepherd boy who was just minding his own business. Roberts-Smith didn’t write that. The Defence Force wrote that, and they basically gave him the green light to do whatever.”

“The fact that you would investigate someone who hasn’t done anything wrong and not investigate someone like Roberts-Smith who’s done a lot of things wrong is a sign of a sick organisation.”

The purpose of these investigations, he argues, was to protect the leadership of the Defence Force. “If the International Criminal Court investigated these crimes, they would go for the leadership, and it would have been catastrophic for Australia.”

The politics of war

McBride’s disillusionment began with Afghanistan itself. The campaign, he argues, was compromised from the outset.

“We were only there to make the Americans happy, to ‘enhance the strategic relationship’. That meant as long as the Americans were happy, it didn’t matter whether Afghans died, it didn’t matter whether we lost the war, it didn’t matter whether we achieved nothing.”

“I believe the main reason we were in Afghanistan, and the main reason America was in Afghanistan, was to stop George W Bush from losing the next election. Dropping bombs is good for votes,” he says bluntly.

For McBride, the war crimes were not the disease but the symptom. “The Defence Force is not fit for purpose. It does not protect Australia; it serves the interests of the minister and the government in charge. And we lie when the truth won’t do. It is a basket case. That’s my real claim.”

Why he did it

McBride insists his decision to blow the whistle was not motivated by self-interest but by duty.

“Despite what my critics say, I haven’t gotten anything out of this. I’m in prison, I’ve lost my job and the life I had. I’ve got about $2000 in my bank account – probably enough to feed my dog, and that’s it. And I’m not complaining, but the idea that there’s some sort of self-interest underpinning what I’ve done is offensive.”

“Some of my critics might say I take it all too seriously, but I don’t think you can take it too seriously. Real people’s lives are involved here.I had a duty to speak up because I could see that the Defence Force was rotten.”

“This will be important for Australia in 100 years’ time,” McBride says. “Unless someone says the truth matters, the law matters, and it’s not all one big media game, we’re screwed.”

McBride will remain in prison at least until August 2026, when the Attorney General will decide whether to grant him parole. He says the sacrifice is worth it.

“We’ve got a great country, we’ve done a lot of things right, and it’s worth fighting for. We have to leave a decent world for our children.”

Defence chiefs buried leak investigation while pursuing David McBride

Stephanie is a journalist with a background in both law and journalism. She has worked at The Guardian and as a paralegal, where she assisted Crikey’s defence team in the high-profile defamation case brought by Lachlan Murdoch. Her reporting has been recognised nationally, earning her the 2021 Democracy’s Watchdogs Award for Student Investigative Reporting and a nomination for the 2021 Walkley Student Journalist of the Year Award.