Generation Z has bigger issues to worry about than the $3m super threshold. When they retire, their super may be needed to pay off their $11m home. Harry Chemay models it.

As the 48th Parliament commences, several pieces of unresolved legislation will be brought forward by an emboldened returning Labor government.

One of those will be the bill, stalled in the previous Senate, to increase the tax on individual super balances of $3m or more, the so-called ‘Division 296’ tax measure.

The Government will find it easier to navigate the new Parliament, picking up three Senate seats, the same number lost by the Coalition. The Greens retain 10 seats, while the independents halve in number from 6 to 3 seats.

All told, it should be an easier path through both Houses for legislation brought forward by the Government, and the Division 296 tax bill may therefore be one of the first stalled pieces of legislation to be negotiated.

Knowing the numbers on the floor aren’t favourable, the parliamentary break has seen a flurry of media activity aimed at creating widespread community backlash against the proposed tax.

To do so, you need to convince people that what appears to be a measure aimed at the top 0.5% of taxpayers will one day hit average workers, due to the proposed bill not indexing the $3m for either inflation or wage growth.

With no shortage of Div 296 opponents, the past few weeks have seen all manner of experts creating models that have today’s Generation Z accumulating fabulous wealth in superannuation, well beyond $3m by the time they retire.

Why let others have all the fun? I thought I’d join the modelling blitzkrieg to see where my numbers land.

‘Joshua’s’ super journey

Joshua is the archetypal 25-year-old Australian male. So typical is Josh that his was the most popular name for male babies born in the year 2000.

Josh is a typical 25-year-old male in every other way as well. He went to uni, has an outstanding HECS/HELP debt of around $30,000 and currently earns $80,000 per year, on which his employer now pays super guarantee at the rate of 12%, effective 1 July this year. He makes no other contributions to super.

Josh intends to work until the age of 60, without any career breaks or interruptions.

To be consistent with Treasury’s long-term assumptions, I will assume that Josh’s income grows at 3.7% per year between now and 2060. That’s the rate (so-called ‘AWE’) at which I’ll compound 2025 dollars into 2060 dollars, or discount 2060 dollars back into today’s equivalent.

I will assume that Josh’s superannuation balance is currently $17,500, which is the approximate median super balance for males aged between 25 and 29, according to Australian Tax Office stats.

Finally, I’ll assume that Josh’s super earns a return of 7.2% per year until 2060, the historical 33-year return for the median ‘balanced’ option, net of investment fees and tax, according to super researcher SuperRatings.

To favour Josh, I’ll exclude administration fees, insurance premiums and other charges, giving him every chance of hitting that magic $3m mark in retirement.

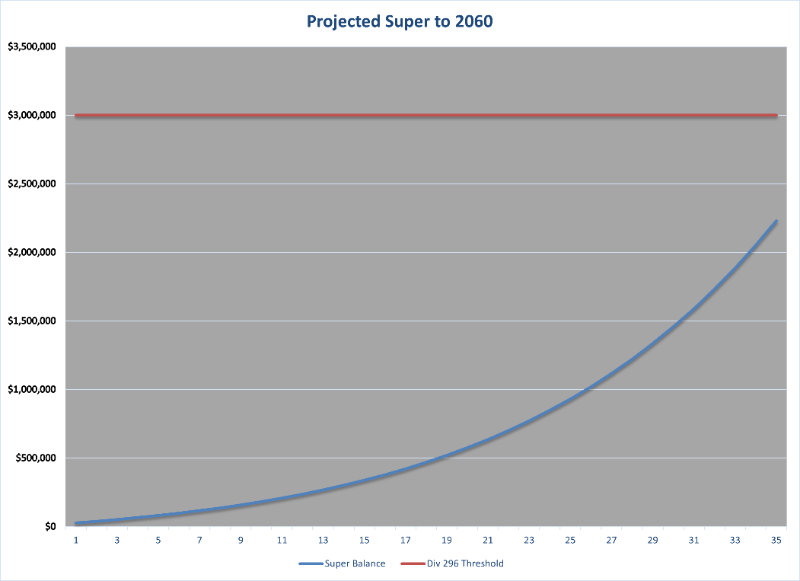

How much super does Josh have as he approaches the age of 60 in the year 2060?

Source: Author’s calculations

Unfortunately, despite 35 years of employer super contributions, growing at 3.7% per year and returning 7.2% annually, Josh falls short of the $3m target by more than $570,000.

His $2.4-odd million in 2060 is equivalent to a balance of around $654,000 in 2025 dollars.

Treasury modelling

My modelling sees Josh fall well short of the $3m Div 296 tax threshold.

Could it be that my assumptions were inappropriate? If so, I’ve unfairly left Josh short when he, like the rest of his generation, might easily attain $3m in super at retirement.

What does Treasury, the government department responsible for modelling long-term superannuation outcomes, have to say on the matter?

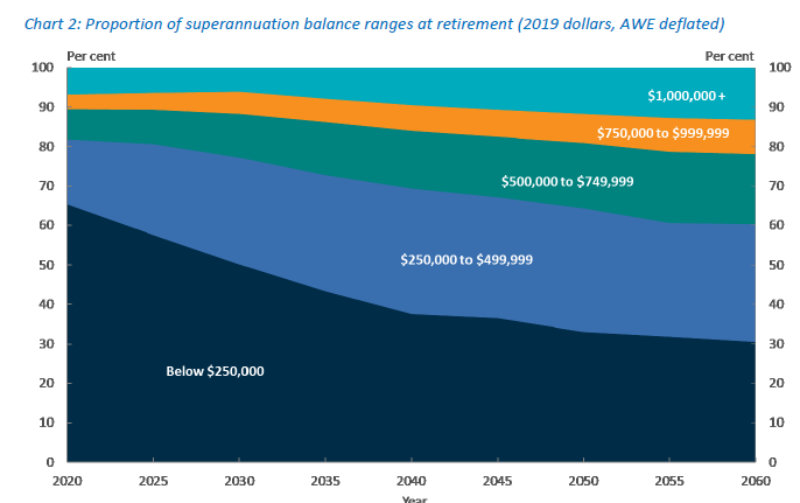

In 2019, Treasury prepared an ‘Information Note’ titled “Superannuation balances at retirement”.

Using its Model of Australian Retirement Incomes and Assets (MARIA), Treasury effectively conducted the very same exercise, modelling super balances out to 2060, using very similar assumptions (the main difference being a slightly higher long-term wage growth assumption of 4% per year).

What did this Treasury modelling suggest? The chart below is taken from that Information Note.

Source: Treasury (2019)

The numbers in the chart above are in 2019 dollars, so we need to compound them out to 2060. When you do, the $500,000 equivalent comes in at around $2.5m. Which you’ll note is past the middle point (50% on the vertical axis), and so a little higher than the average outcome.

So yeah, Treasury’s modelling broadly lines up with mine.

Long story short, it is likely that Josh, or any other average income Gen Z for that matter,

will not be impacted by the Div 296 tax based on employer super contributions alone.

The elephant in the retirement room

Like most Gen Zers, Josh would someday like to own a property. That’s no small challenge on his income, with the average capital city house price recently tipping over the $1m mark.

Josh and his partner are saving, hoping to enter the property market around age 37, the median age for first homebuyers today.

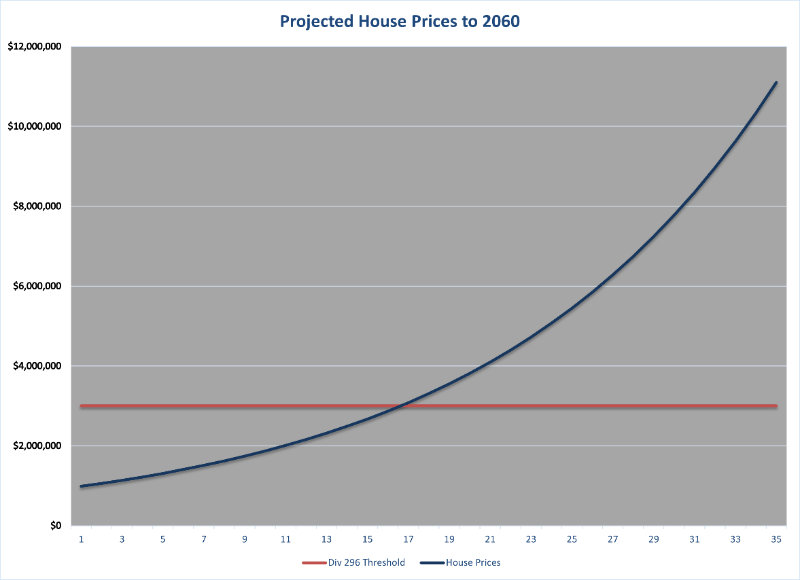

To round out this thought experiment, I’ve modelled house prices out to 2060, using a dataset of average capital city prices going back to 1980. I’ll use the compound growth rate for the 42 years between 1980 and 2022 of 7.4% per year.

What would a mere 0.2% difference per year in growth be between Josh’s super and house prices?

Author’s calculations.

Turns out the $3m Div 296 tax isn’t the biggest problem Josh has as he ages. It’s not even close.

At 7.4% per year, Josh will be facing an average house price of around $2.2m as he and his partner try to get that all-important first foot on the property ladder.

While first-home buyers generally purchase under the average price, I’ll leave you to work out an 80% mortgage on a property of say $1.9m, for a couple whose combined gross income might (in the year 2037) be around $250,000.

Josh and his partner will likely upgrade once or twice, very possibly also upsizing their mortgage as they do. As they approach retirement,

their house may be worth more than $11m, and almost certainly still significantly mortgaged.

If that seems far-fetched, bear in mind that in 1980 median capital city house prices were $68,850 in Sydney (now $1,210,000), $39,500 in Melbourne (now $796,000) and $35,475 in Brisbane (now $926,000).

Josh, his partner and the rest of Gen Z have challenges ahead, but paying Div 296 tax on super is unlikely to be their burning issue, even in the remote event that the $3m remains unadjusted for the next 35 years.

On the balance of probabilities, it is housing affordability and mortgage debt that will, absent some significant policy reform.

Songbirds and snakes. How to end the ‘Hunger Games’ of housing affordability

Harry Chemay has more than two decades of experience across both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. An active participant within the wealth and superannuation space, Harry is a regular contributor to investment websites in Australia and overseas, writing on investing and financial planning.