A two-year MWM investigation reveals top Australian Army Generals may know much more about war crimes in Afghanistan than previously thought. Retired army officer Stuart McCarthy reports.

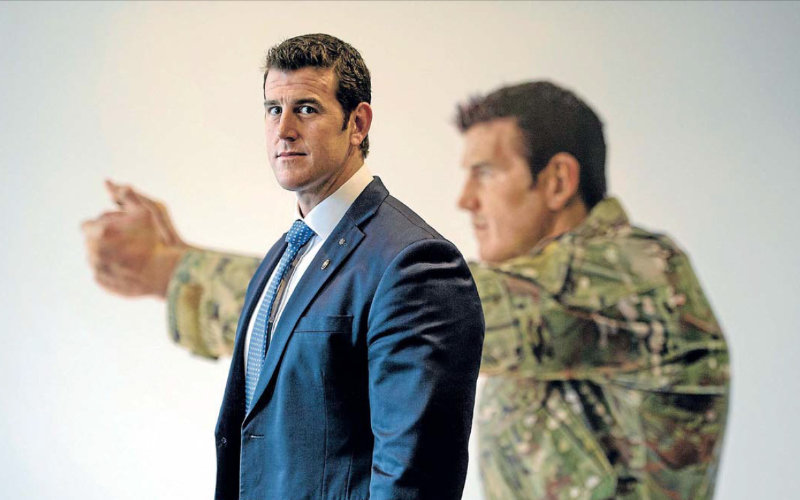

A US Air Force Liberty surveillance plane with top-secret signals intelligence (SIGINT) equipment flew a surveillance mission in support of an Australian special forces raid in Darwan, Uruzgan province, at the time of Ben Roberts-Smith’s alleged war crimes in September 2012.

The aircraft was part of a rapid procurement program that also saw Australian Defence Force (ADF) aircrews and intelligence operatives from other spy agencies attached to the US military intelligence task force conducting surveillance flights over Afghanistan at the height of the 20-year war.

Video imagery and other intelligence gathered by the US aircraft and Australian spies may prove crucial to a war crimes referral sent to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague two years ago, implicating some of Australia’s top generals.

Surveillance flights

The Liberty is a heavily modified Hawker-Beechcraft Super King Air 350 (SKA 350) twin-engine turboprop aircraft, fitted with a suite of top-secret SIGINT equipment and a multi-spectral full motion video (FMV) camera.

Dozens of these unarmed aircraft were rushed into service in Afghanistan and Iraq by the Obama administration in 2009 to address delays in the production of armed ‘Reaper’ and ‘Predator’ drones. Similarly equipped civilian aircraft flown by ex-military crews were contracted to the same US-led task force, operating across the Middle East and North Africa. Publicly-released, high-resolution footage from Reapers and Predators striking suspected terrorist targets – or civilians – feature prominently in legacy media and online coverage of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, NATO’s attacks on the Gaddafi regime in Libya in 2011 and the US military’s more recent involvement in Syria.

US Air Force MC-12W ‘Liberty’ intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft (Image: US Air Force)

Liberty, Reaper and Predator share the same type of FMV camera, the L3Harris Wescam MX-15, also commonly fitted to helicopters and other fixed-wing aircraft used by law enforcement and search & rescue agencies across the globe.

The US-led ISR task force in Afghanistan collected 1,000 hours of FMV footage per day in 2012. A communications specialist assigned to the task force during this period told MWM the Kandahar detachment alone was conducting as many as 36 MC-12 or contracted SKA 350s flights each day, collecting around 140 hours of FMV footage and SIGINT data over a given target area.

An Australian intelligence operative who flew approximately 70 ISR missions on civilian SKA 350s fitted with the same camera and SIGINT equipment on contract to the US task force told MWM:

“There are quite a few ‘what-ifs’, but the MX-15 camera certainly had the ability to capture high-res video footage of potential war crimes taking place, if the operator was pointing in the right direction and zooming in on the right area. The question is – what edited footage was included in intelligence and operational reports up the Australian chain of command … and who has the full video files now?”

While much of the FMV footage from various ISR aircraft operating over Afghanistan and Iraq was declassified and made public during and after those wars, classified US military documents obtained by MWM show the FMV footage taken by the USAF MC-12s and contracted civilian aircraft was usually upgraded from “secret” to “top secret” – the highest level of security classification – whenever it was “fused” with additional top secret data such as the tracking of mobile phone transmissions from high-value targets or “persons of interest.”

Top secret SIGINT mobile phone tracking technologies were key to the success of the US-led coalition’s kill-capture missions against Al Qaeda and Taliban leaders through much of the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Five Eyes

The sharing of this type of highly classified material is part of the multilateral “Five Eyes” treaty between Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US. In Australia and elsewhere, similar SIGINT and aerial surveillance capabilities have since been outsourced to government-funded private security companies such as Omni Executive, which employs ex-military personnel who retained their top secret security clearances after leaving the defence force.

The Liberty has a crew of four, including a pilot, co-pilot, ISR sensor operator and classified communications operator. In Afghanistan, a fifth member of the crew was usually located with the ground force tactical commander, providing live video footage and a secure communications link with the aircraft as it loitered over the target area.

Defence sources who were directly involved in the Australian Special Operations Task Group’s (SOTG) kill-capture campaign against the Taliban in southern Afghanistan told MWM the USAF Liberty was “the ISR platform of choice” for the SOTG during this period. The Liberty had a “lower signature” and was able to respond more quickly to calls for support than other aircraft such as the RAAF Orion. USAF MC-12s and contracted SKA 350s were based at Kandahar and Bagram airfields in Afghanistan, while the RAAF Orions were three hours away at Al Minhad Air Base near Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. One source told MWM:

“The ISR aircraft over Darwan was an MC-12, with the video feed going straight into the ops room and the forward command element out on the ground. If not an MC-12, it was one of the contracted SKA 350s.”

From 2009 to 2013, USAF says its Liberty squadrons played a key role in killing or capturing more than 700 high-value insurgent targets in Afghanistan, with a 99.9% response rate for ISR support requests from US and allied ground troops. The motto of the Bagram-based Liberty squadron was “Find, fix, finish.” One of the USAF Captains from this squadron said in early 2014:

“We use our tactical systems operator to help find the enemy. We then fix on the enemy with a camera operated by our sensor operator, and then we are part of the kill-chain as well; we guide other assets onto the target to be able to either eliminate or capture the enemy forces.”

Another Defence source who served in Afghanistan during this period told MWM:

“There were a few RAAF or ex-RAAF pilots attached to the Liberty units in Afghanistan. I can’t recall numbers, but I do know some of the Liberty ISR missions across Afghanistan were actually flown by Australian pilots. Sigint specialists from ASIS [the Australian Secret Intelligence Service] and ASD [the Australian Signals Directorate] were also directly involved in the Liberty ISR task force to some extent.

There’s little doubt much of their ISR product would have gone to Canberra … regardless of the normal ADF or US military reporting chains.

The Darwan mission

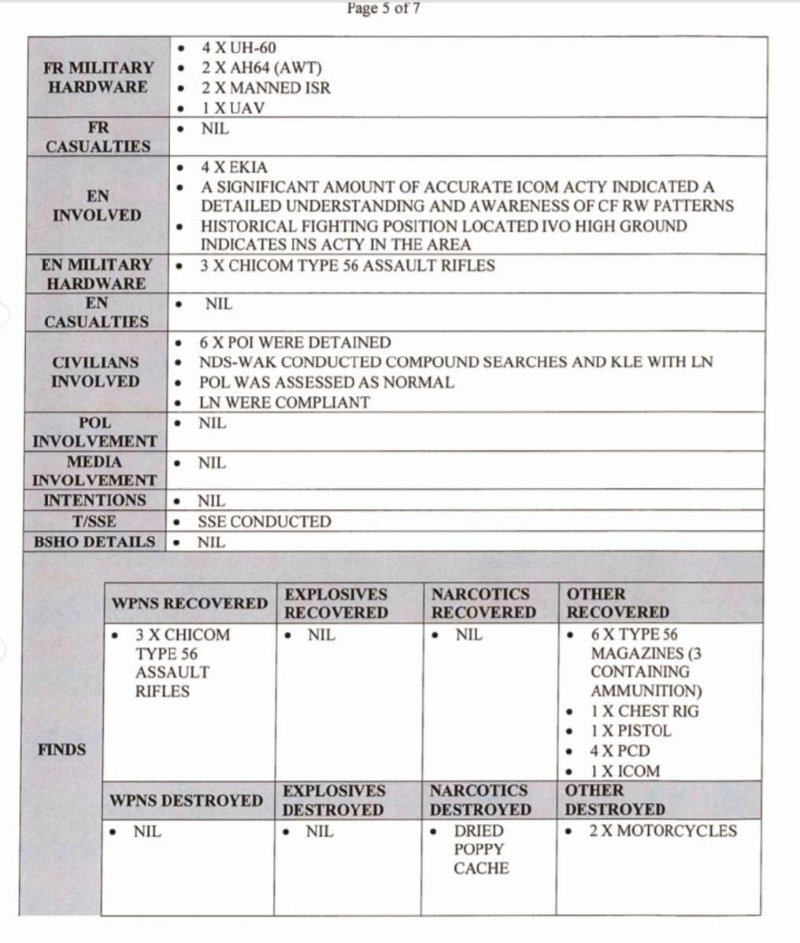

Classified SOTG documents obtained by MWM show two Liberty aircraft were assigned to perform this role in support of the cordon and search mission at Darwan in Uruzgan province on 11 September 2012, where Ali Jan was allegedly executed. The raid involved 42 Australian soldiers from SAS 2 Squadron headquarters, SAS Golf Troop and 2 Commando Regiment’s November Platoon, with a “partner force” of 18 Afghan National Directorate of Security (NDS) ‘Wakunish’ commandos.

They were flown from the multi-national base at the Uruzgan provincial capital of Tarin Kowt (MNBTK) to the remote Darwan village just after 5.30 am in two ‘turns’ of four US Army UH-60 ‘Blackhawk’ utility helicopters.

Further support came from two US Army AH-64 ‘Apache’ gunship helicopters and one unmanned ISR drone, most likely a RAAF Heron. One of the Liberty aircraft circled above Darwan, providing live surveillance footage to the troops on the ground for the duration of the six-hour raid. The second Liberty remained on standby until it was stood down as ground operations concluded and the troops started returning to MNBTK on the Blackhawks. At 10.54 am, the SAS 2 Squadron operations officer wrote in the SOTG operations chat room:

“For ISR manager – limited value in the second [Liberty] mission this afternoon (for both [2 Squadron] and fusion and targeting cell). In order to conserve hours for a more viable targeting period, please stand down the second mission.”

As many as six “persons of interest” were detained by the SOTG during the Darwan search, then flown back to MNBTK and transferred to the ADF detention facility just before midday.

Defence sources have told MWM the tip-off for the raid came from corrupt, illiterate Afghan warlord Matiullah Khan, who at the time was the Uruzgan police chief. He was reportedly killed by a Taliban suicide bomber several years later in Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul.

Uruzgan police chief and corrupt local warlord Matiullah Khan (centre) greets Australian Army Brigadier Roger Noble (left, facing away from camera) during a visit to Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan in 2012 (Image: ADF)

Further details on the direct involvement of Australian pilots or SIGINT specialists in surveillance flights by USAF, ADF, other allied military or contracted ISR aircraft supporting the SOTG during this period are part of MWM’s ongoing investigation into higher command cover-ups.

The Office of the Special Investigator – the law enforcement agency established by the Morrison government to investigate the war crimes uncovered in the 2020 Brereton Report – responded to our query on whether they have accessed the relevant FMV footage or other SIGINT products during their investigations with, “The Office of the Special Investigator does not comment on operational matters.”

Extract from the Australian Special Operations Task Group classified ‘Operation Summary’ for the cordon and search operation at Darwan village, Afghanistan on 11 September 2012, listing the aircraft and other supporting assets.

“We got him”

The Darwan raid was part of the SOTG’s pursuit of Sergeant Hekmatullah, a rogue ANA soldier who murdered Australian soldiers Sapper James Martin, Lance Corporal Stjepan Milosevic and Private Robert Poate and wounded two others in a so-called “green on blue” insider attack at Patrol Base Wahab north of Tarin Kowt on the night of 29 August 2012.

Capturing Hekmatullah became the SOTG’s highest priority, and they received extensive support from other Australian and allied military units and spy agencies. Announcing Hekmatullah’s eventual capture in Pakistan in October the following year, then Defence chief General David Hurley briefed a packed Canberra press conference on the involvement of ASIS, ASD and other Australian and international spy agencies in the broader operation.

One of the agencies included in Hurley’s long list of accolades was Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) – an organisation known to have

facilitated the provision of weapons, explosives, child suicide bombers, training, finances and other material support to the Taliban throughout the Afghanistan war.

Among the early raids in the SOTG’s pursuit of the rogue Afghan sergeant was a 31 August cordon and search at Sola on the eastern outskirts of Tarin Kowt, two days after the Australian soldiers were murdered.

According to then Defence Minister Stephen Smith, the Sola operation involved 60 SOTG personnel and 80 Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers. The raid resulted in the deaths of two local civilians – 70-year old imam Haji Raz Mohammad and his 30-year old son Abdul Jalil. When Afghan President Hamid Karzai publicly complained about the killings, his complaint drew only a reflexive denial from Smith, who said in a press conference, “I’m advised by the Chief of the Defence Force [Hurley] that the two people who were killed have been confirmed as insurgents.”

According to Defence sources, the “confirmation” process consisted of SOTG officers having a discussion with police chief Khan, who routinely gifted expensive watches to incoming SOTG commanding officers, among other Australian officials. SMH columnist Peter Hartcher wrote of Karzai’s complaint about the killing of these two civilians who were “confirmed as insurgents” via the say-so of this corrupt Afghan warlord, “Hamid Karzai’s criticism of Australian troops on the weekend was an intolerable attack from an intolerable leader.”

Afghan Files

The eventual ADF investigation report into the Sola killings, summarised in the ABC’s ‘Afghan Files’ in 2017, found that Haji Raz Mohammad “was initially compliant, but then tried to grab [an] Australian’s weapon, so the Australian soldier shot him dead,” while Abdul Jalil was shot dead after being seen talking on a radio as helicopters approached to extract the Australians as the operation concluded.

The possibility that the Sola killings may be war crimes was first reported in the legacy media almost eight years later, by ABC Four Corners in March 2020. Three months after this story aired, Fairfax tried to introduce the ABC’s “fresh allegations” about Roberts-Smith’s conduct at Sola into the defamation proceedings, asking the Federal Court if it could change its defence to include the ABC’s reporting on the Sola incident and another October 2012 killing at Syahchow village in Uruzgan province.

Roberts-Smith’s barrister Bruce McClintock SC responded in court, “Fairfax have led no evidence about the source of the information now relied on – this is stark in relation to Sola.”

In June 2023, the 7.30 Report updated the ABC’s coverage of the Sola killings and the ensuing “diplomatic incident” between Karzai and Smith, now alleging the direct involvement of Roberts-Smith by name. The story was based on a leaked excerpt of the unredacted, classified Brereton report and an excerpt from a classified ADF investigation report that named Roberts-Smith but “found the shooting was justified because the imam was seen talking on a radio.”

Brereton Report

Despite the fact that Roberts-Smith’s direct involvement in two suspicious deaths and the victims’ identities were known by senior Defence officials and the minister almost immediately after the incident occurred, the Corporal remained on active duty even while a so-called “investigation” was underway. The Darwan raid that resulted in Ali Jan’s death took place 11 days later.

The heavily redacted Brereton Report found evidence of 39 murders of civilians by, or at the direction of, Australian special forces troops in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2013. Among Brereton’s other findings were that some SOTG soldiers used “throwdowns” of weapons or radios planted on the bodies of dead civilians, or falsely reported hostile behaviour by local Afghans, to conceal or justify murders or other crimes.

But some of these exact concerns were raised at least as early as March 2012, in an investigation conducted by an ADF officer in a senior International Security Assistance Force appointment. The officer wrote in his report that local concerns over civilian casualties at the time:

… may also require a review of the burdens of proof as they pertain to the necessity of engaging spotters perceived to be directly participating in hostilities.

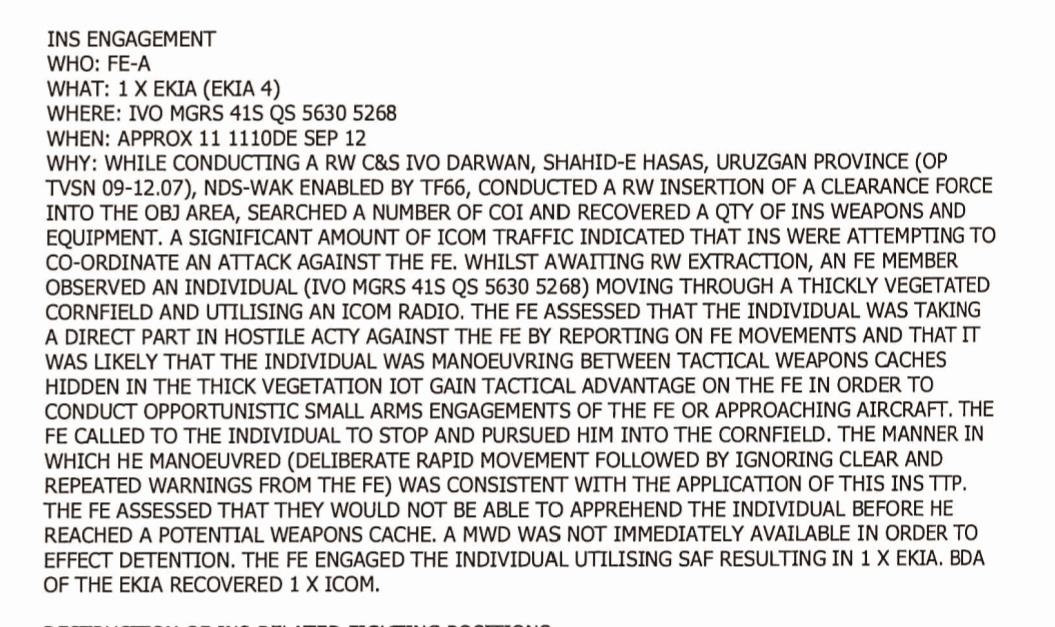

The classified SOTG documents obtained by MWM covering the immediate reporting of Ali Jan’s death at Darwan suggest no such review was done. The elderly civilian was the fourth “enemy killed in action” (EKIA) reported by SOTG soldiers up through their tactical command chain during the Darwan raid, using the same apparent cover story.

At 2.37 pm, the SAS 2 Squadron operations officer entered a “post-debrief consolidation” of key events that took place during the morning’s cordon and search. The account provided to SOTG officers from the soldiers involved in the killing of Ali Jan was summarised:

“Whilst awaiting [helicopter] extraction [on the second turn of Blackhawks], an [SAS soldier] observed an individual moving through a thickly vegetated cornfield and utilising an Icom radio. The [SAS patrol] assessed that the individual was taking a direct part in hostile activity against [them] by reporting on [their] movements and that it was likely that the individual was manoeuvring between tactical weapons caches hidden in the thick vegetation in order to gain tactical advantage on [them] in order to undertake opportunistic small arms engagements of [them] or approaching aircraft … The [patrol] assessed that they would not be able to apprehend the individual before he reached a potential weapons cache. A military working dog was not immediately available in order to effect detention.”

On this pretext, EKIA 4 was shot dead, destined to become part of Australia’s biggest ever defamation case a decade later.

Extract from a classified printout of the SOTG operations chatroom, showing the “post-debrief” account of the killing of “EKIA 4” during the extraction phase of the cordon and search operation at Darwan, Afghanistan on 11 September 2012.

Who has seen the footage?

Brereton found no criminal command responsibility on the part of senior ADF officers for any of the 39 murders he identified from 2009 to 2013, including this “EKIA” now understood to be Ali Jan. On the subject of aerial ISR assets potentially detecting criminal misconduct, Brereton’s heavily redacted report lists a number of “impediments” to commanders at company or squadron level, but no higher. The section detailing specific incidents, including the killings at Sola and Darwan, is entirely redacted.

Several sources involved in the Brereton inquiry have told MWM they believe video surveillance footage from aerial ISR platforms was used during the inquiry, but not shown to the suspects during the proceedings.

The inquiry was held under the administrative legal framework of the Inspector-General of the ADF, which does not afford witnesses or suspects the same legal rights to challenge evidence that are afforded in criminal proceedings.

The sequence of events between Sola and Darwan and its significance to the question of higher ADF criminal command responsibility have thus far been ignored by Fairfax, the ABC and the rest of the legacy media, despite their privileged access to repeated Brereton leaks from senior Defence officials.

They didn’t know, really? Pursue top brass over alleged war crimes in Afghanistan, says veteran

The passage of high-resolution ISR video footage from the USAF Liberty aircraft and other surveillance platforms involved in the hunt for Hekmatullah, up through the Australian operational command chain,

is now one of the keys to this command responsibility question.

Under the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, military commanders or civilian superiors who knew or should have known crimes were being committed but failed to prevent further crimes, can themselves be prosecuted as war criminals. The respective war crimes provisions of the Australian Criminal Code, adopt a tougher “knew or was reckless” standard. The Albanese government’s failures to initiate criminal proceedings against ADF generals saw Senator Jacqui Lambie refer this to The Hague two years ago.

Did Australian generals or politicians know – or should they have known – war crimes were being committed by Australian special forces soldiers in Afghanistan? And what if any actions did they take to prevent further crimes? Were they reckless?

We will address these and other questions in Part Two.

Australia’s Afghanistan war crimes a serious challenge for Albanese government

Stuart McCarthy is a medically retired Australian Army officer whose 28-year military career included deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq, Africa, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Stuart is an advocate for veterans with brain injury, disabilities, drug trial subjects and abuse survivors. Twitter: @StuartMcCarthy_