The Reserve Bank’s numbers shout that it made a mistake not cutting interest rates in April, as well as yesterday. The forecast drop in real wages underlines the need, Michael Pascoe writes.

I hope you enjoyed this financial year, when real wages actually rose for a change, because next year, they’re going backwards again.

And that is just one of the reasons why the Reserve Bank will indeed cut interest rates twice more this year, and was wrong not to cut in April as well. Here’s the scoop about real wages that is nearly always overlooked by economists and about which the general commentariat is totally ignorant:

the simplistic comparison of the wage price index and the consumer price index ignores the impact of tax.

Quick example: The RBA is forecasting the wage price index and the CPI will both rise by 3.1 per cent in the new financial year. Simple souls who have never done the maths will think that means real wages will be static. They have no idea about the nature of our tax system.

Give a 3.1 per cent pay rise next year to someone on $100,000 and they will actually only get a 2.7 per cent pay rise after tax – and that’s what counts in the real world.

Give a 3.1 per cent pay rise to someone on $50,000 and they will only get a 2.4 per cent pay rise in their hand.

I won’t bore you with the numbers this high in the column, but I’ll include them at the end if you don’t believe me – an exercise I’ve had to do over the years with economists I respect.

Inflation fear

It looks like I need to go through the exercise with the RBA, as the bank remains scared of what it perceives as a “tight” labour market, causing inflation to take off again.

RBA Governor Bullock said on Tuesday that inflation was “nearly” where the bank wants it to be. This tells me two things: the governor doesn’t believe the bank’s own reading of the present, never mind its forecasts; the bank continues to drive monetary policy by looking in the rearview mirror, and its claims of being “forward-looking” are rubbish.

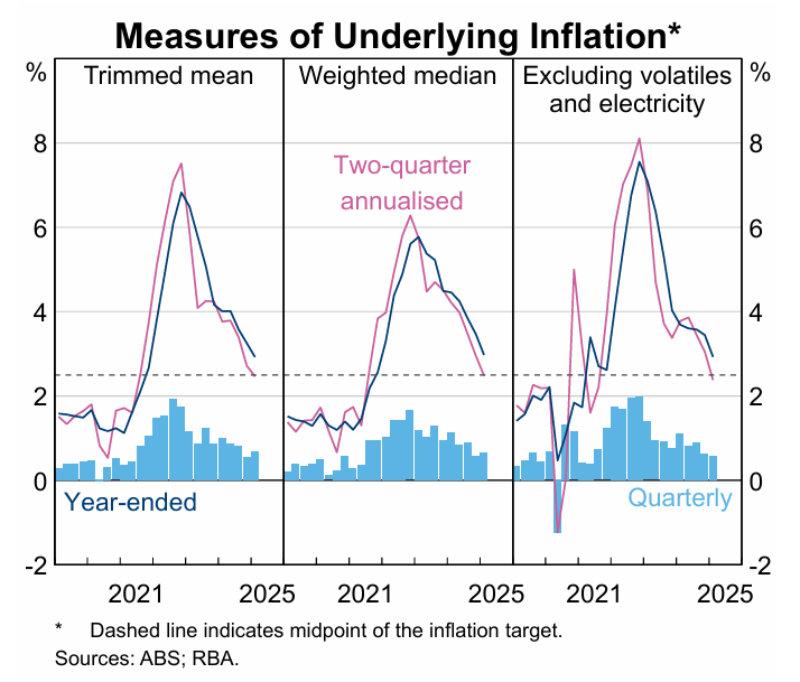

The reality, as demonstrated by the bank’s graphs, is that its dubiously preferred trim mean measure of inflation has been running right on its pinpoint target of 2.5% since September, as shown by annualising the figures for the past two quarters.

Just as important, the bank’s forecast for this financial year – the one that ends in one month and 10 days – is that annual trimmed mean inflation will come in at just 2.6 per cent. That’s a bee’s appendage from the target.

The bank claims the domestic economy has rolled pretty much in keeping with its February forecasts, so it remains a mystery to me why it didn’t cut in April.

I asked the governor the wrong question during Tuesday’s media conference. I asked if not cutting in April had been a mistake. I should have asked if, with the benefit of hindsight, the bank should have cut in April.

Given my mistake, Governor Bullock was able to point out that the bank did not have the March quarter inflation numbers at the time and that she doesn’t trust annualising a quarter’s numbers. What her answer indicated is that the bank totally ignores the monthly CPI measure from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. So much for being “data-driven”.

Sure, the monthly number isn’t as robust as the quarterly figure, but the lived experience of the past year is that it’s turned out to be pretty damned good. A monthly figure obviously is closer to the present, while a quarterly figure is well in the past.

What also became clear in the media conference is that the RBA remains spooked by a labour market that it can’t quite believe.

Labour market fear

Despite an unemployment rate of around 4.1 per cent delivering inflation exactly on target, the bank’s various, more subjective measures of the labour market allow it to keep claiming the market is “tight” rather than the desired “full”.

Memo RBA: Businesses will always tell you they have trouble getting enough good workers unless we’re in a recession. It’s part of the excuse our often second-rate management uses for lacklustre performance.

Reading between the lines of the bank’s quarterly statement on monetary policy, there seem to be economists within the bank who believe what the data is telling them, even when the board does not, staff who manage to work qualifying phrases into the official line.

For example:

“With labour market conditions steady recently, we continue to assess that the labour market is tight, although there is considerable uncertainty around estimates of full employment. The rate at which workers move between jobs has continued to trend downwards over recent quarters, which might indicate less upwards pressure on wages growth and inflation than implied by the unemployment rate. Nevertheless, recent wages growth outcomes have been in line with expectations in the February Statement, though growth in unit labour costs remains high and has been stronger than expected.”

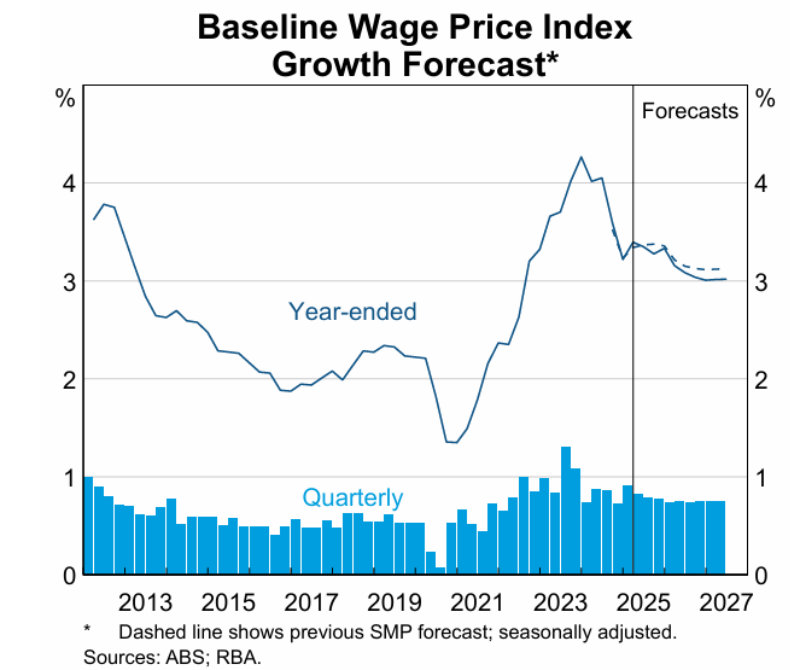

Whatever the internal tussle, the official forecast is for wages growth to fall to just 3%. If the bank’s inflation forecasts are correct, it means

not enough to achieve actual growth in real take-home pay in the years ahead.

That means household consumption will remain soft, and we’ll continue to go backwards on a per capita basis. SNAFU.

If you’re still with me and want proof of what tax does to a theoretical pay rise, here it is, two examples.

- Ignoring family benefits and whatever tax lurks might be available, someone on annual pay of $100,000 should pay $24,967 tax and take home $75,033. With a 3.1 per cent pay rise to $103,100, they will pay $26,037 tax and take home $77,064. That take-home pay rise of $2,031 is a gain of 2.7 per cent.

- On $50,000 this year, you pay $7,717 and take home $42,283. With a 3.1 per cent pay rise, your $51,550 gross means paying $8,252 tax and taking home $43,298. That’s an increase of $1,015 in take-home pay, 2.4 per cent.

Purchasing power keeps going backwards. The “cost of living” crisis lives on.

Michael Pascoe is an independent journalist and commentator with five decades of experience here and abroad in print, broadcast and online journalism. His book, The Summertime of Our Dreams, is published by Ultimo Press.