Mismanagement of the Murray Darling Basin has now reached such farcical proportions, it’s hard not to be reminded of Mark Twain’s edict “Truth is Stranger than Fiction”. How did this level of ineptitude, cock-ups, rorts and cronyism flourish unchecked for so long? Triskele examines the many angles of the Watergate scandal and reports.

THE WATERGATE scandal has produced all sorts of interesting angles. One of my personal favourites goes like this: this is a political beatup. Water markets are gonna do what water markets are gonna do. Some smart folks will benefit from it. Some of those benefits might make it to the Cayman Islands.

So what. Move along. Nothing to see here.

“Whataboutism” and bait-and-switch arguments that aim to divert people onto irrelevant, not fairly comparable, or otherwise distracting tangents are classic public relations management techniques. As long as people don’t recognise them as such, they will continue to be ridiculously easy to implement, and highly successful. They are the rhetorical equivalent of blinding the fish by injecting a large dose of squid ink into the water.

Mick Keelty

Most Australians intuitively grasp what has gone wrong in the Watergate water market buyback story, which is: you can’t cultivate an ecosystem favourable to sharks and expect it to be inhabited by goldfish. Mick Keelty (former Australian Federal Police Commissioner and current Northern Basin commissioner for the Murray-Darling Basin) goes straight to this point when he recently said that the river system was “ ripe for corruption”.

“you can’t cultivate an ecosystem favourable

to sharks and expect it to be inhabited by goldfish”

Pointing to the existence of undeclared conflicts of interests that currently operating in the water market, he told The Saturday Paper:

I’m not saying it’s corruption; I’m saying it’s conflict of interest…But you could draw a conclusion that if conflicts of interest aren’t transparent, it could lead to corruption…Water is now the value of gold. If you have corruption in other elements of society, if you have corruption in other areas of business, why wouldn’t you have it here, when water is the same price as gold?”

The story most of us intuitively understand is that the Watergate scandal is a story about how certain people may have leveraged networks of influential professional, personal, and political relationships, and possibly insider knowledge, to achieve outcomes in their narrow self-interest, and against the broader public interest.

You’d really have to work hard not to get this point.

Many people use the image of a spiderweb when they talk about networks of influence. I prefer the image of a mimosa tree. As anyone who has tried to eradicate one of these pests manually will know, it has a tangled, jumbled, and very, very long root system which seemingly runs forever horizontally under the topsoil as well as deeper into the earth. You can’t tell where one root begins and another ends, or how they are interconnected, but you can be sure that you have never eliminated all of them. Unless you are eternally vigilant of that root system, reshooting and plague-like spreading of the mimosa is inevitable.

This image seems entirely appropriate for what I am arguing here.

One of the two central issues to emerge from this story is that of ministerial and departmental responsibility at the federal level. There is really no arguing around this one, no matter how much Joyce blathers unhinged about other governments and other ministers (the usual rhetorical distractions). (You can listen to Barnaby Joyce’s bizarre interview with Patricia Karvelas on ABC RN below.)

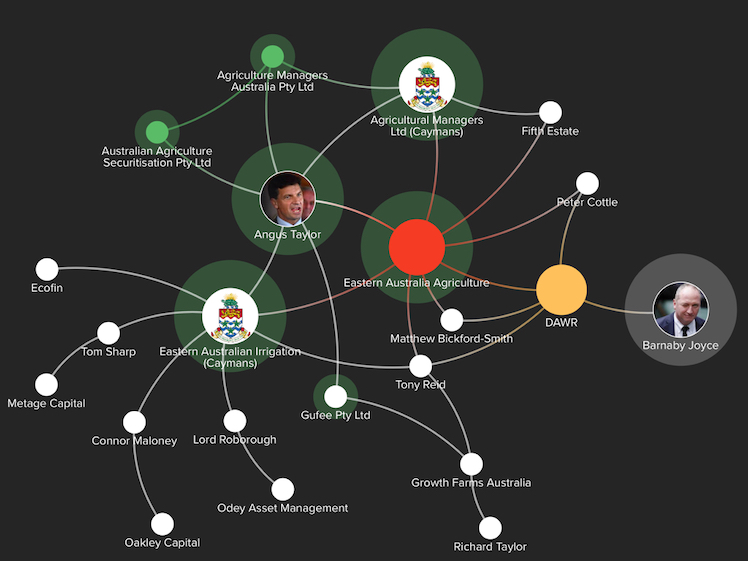

The second central issue is whether there was a network of influence operating in the background linking influential and moneyed cotton interests, Barnaby Joyce and Angus Taylor.

Did the Watergate scandal deliver a knockout punch in this sense? Not really. The ecosystem works in such a way that this is highly unlikely to happen. However, as we can see from the graphic below, the story features most of the factors that lead Australians to detect the whiff of the swamp: political and possible personal connections; opaque financing arrangements; family trusts and offshore tax havens; creative accounting; speculation; possible insider knowledge; political donations; lobby groups and consultancies; legal threats; attempts to block or edit the publication of truthful and publicly available facts; and obfuscation by public authorities, by redacting information of interest to the public and engaging in endless blame-shifting. I won’t repeat these story-lines here: if you’ve been living under a rock, you can find summaries from different perspectives of what the issue is about and how it evolved here and here. There are also the articles published right here on this site by Michael West. See here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here,

Mud map graphic courtesy of @jommy_tee

None of this can be clarified without a full judicial enquiry/Royal Commission, and ironically, the very same financial and political mechanisms that create the intrigue are also stopping the story from going away.

In a recent edition of The Saturday Paper, professor A.J Brown of Griffith University pointed to four major areas in public life that needed to be addressed in order to restore public faith in politics – that is to say, to creative a political ecosystem suitable for its inhabitants.

The first of these is reform of political donations and campaign finance reform. The second of these is greater control on lobbying and improved codes of conduct for politicians and their staff.

The third is proper whistleblower protections — to which I would add, and a review of the stultifying effect that legal bullying and defamation threats are having on journalism and political debate in this country. The fourth is much greater corporate and financial transparency.

As the Grattan Institute put it in its report “Who’s In the Room? Access and influence in Australian Politics”, “Australians want to drain the billabong: they don’t like the current system and they don’t trust it”.

Keelty is apparently examining Australian Electoral Commission records of political donations, mapping out the relationships between donors, politicians and water bureaucrats, and the recipients of water licences or contracts. We will all look forward to the results of this work. My focus here is on that other source of conflicts of interests – special interest groups.

Enter the lobbyists

As the Grattan Institute report argues, Australia is subject to policy capture by special interests. Special interests -groups or organisations who have much to gain from a particular policy position – can and do engage in rent-seeking – basically, creating windfall gains for themselves by influencing government to secure interventions “that further their interests at the expense of the public interest”. Rent-seeking, the authors argue, is “more likely to be successfully where the policy area in technical, niche, or complex”. Interestingly, industries that are highly regulated by government are particularly prone, precisely because it is hard for outsiders to understand.

Access to politicians is an important lever in securing favourable policy outcomes. The Guardian has provided access to a scape of four year of data from ministerial diaries which provides basic information about formal meetings held with ministers, premiers and deputy premiers.

Examination of the data is no simple task. The Guardian had to scrape the information off four years of PDF records from ministerial diary disclosures. Entity names and ministerial portfolios are not recorded in the same way. Some work had to be done to account for multiple entities attending the same meeting. The information recorded also has other shortcomings. It only reflects formal meetings with ministers, not other key staff, and it does not include any detail on the content of the meeting.

We have extracted some data about meetings between big irrigation interests and NSW minister. The NSW Irrigators’ Council tops the list, with 27 meetings with ministers held over 2014-2018. Murray Irrigation – which runs irrigation distribution systems but also trades in water – came in second at 17 meetings to discuss water issues explicitly, plus one to discuss a “stakeholder dinner”. Other significant attendees at meetings were the Rice Growers (12 meetings), Cotton Australia (11 meetings), and Namoi Water (10 meetings). Other significant corporate interests like Murrumbidgee Irrigation, Gwydir Valley Irrigators Association Inc, the National Irrigators’ Council, and Macquarie River Food and Fibre are also well represented. Murrumbidgee Irrigation, which met with ministers eight times, has recently been on the news because it is involved in a fight with other landholders over a multimillion taxpayer-funded private irrigation program. This case seems to be a clear example of the David and Goliath power differentials and different levels of access I am talking about.

Formal access to ministers is not the only way to secure influence over policy discussions and political outcomes. As the Grattan Institute report puts it, “Access to senior policy makers is crucial to influence.” We have no way of knowing from ministerial diary output how much contact there is between special interest groups and junior ministers, policy makers, and other bureaucrats and staffers.

What is more, access can be informal and via webs of personal relationships.

Relationships matter and can be bought, says the Grattan Institute. The authors note the large and growing share of former government officials who become federal lobbyists -one of the many revolving doors in Australian politics. Indeed, they find that since 1990, about a quarter of former federal ministers or assistant ministers have become lobbyists after political life. Katrina Hogkinson, the NSW water minister who altered the NSW Barwon-Darling water-sharing plan after representation from a cotton lobbyist, and now National Party candidate in the marginal seat of Gilmore, was recently forced to deny she is on the payroll of one of Australia’s most powerful lobbying firms — hilariously, the denial came via an email sent from her lobbyist email address. There is probably nothing to see here, but again — there’s that whiff of swamp…

Nationals' #Gilmore candidate Katrina Hodgkinson still on lobbying firm's payroll but argues she is not a lobbyist, just an adviser to lobbyists. Jesus, Mary & Joseph. ? #ausvotes #auspol https://t.co/P32VH12Oxk

— Sandra K Eckersley? (@SandraEckersley) May 2, 2019

Special interest groups- who do they represent?

The irrigator peak groups claim to represent the interests of a broad collective, namely, irrigators. However, power relationships exist in all groups, and not all irrigators are the same. Horticultural irrigators do not necessarily have the same interests as cotton, nut and rice producers; and even within these sectors, there are huge agribusinesses working alongside much smaller family operations, with great discrepancies of power between them. Just ask Chris Lamey.

Given this context, it should be obvious that farmers and irrigators do not have uniform opinions on water policy or water management. When the NSW Irrigators’ Council makes firm claims about the policy preferences of irrigators -such as against water buybacks and favour of on-farm infrastructure spending, for instance- they are not accurately representing the much more nuanced views of irrigators. It is not hard to find voices of farmers who argue that the system is skewed towards the interests of a select minority. You only have to go to the submissions of the South Australian Royal Commission for that. There is a very real and widespread perception that the system is being run for big corporate interests and there is wide sense of lack of faith in government and in water management. While the irrigator lobbies are well represented in government offices, there is evidence of lack of sufficient meaningful engagement and consultation with farming communities and the subsequent erosion of social trust.

At its most blatant, as in the case of the McBrides of Tolarno, you could be publicly threatened by a representative of Cotton Australia (which Cotton Australia has denied). However, power is rarely deployed as obviously as that. In a poignant article, Anson Cameron describes how a local citizens’ enquiry can be chilled into silence just by the appearance of the big cotton lobbyist to deliver the company line about the state of river being due to the drought. For anyone who wants a sharp analysis of what the intimidating effect of power looks like when deployed by local big wheels in small communities, this is your go-to piece.

We only have this partial picture of who is traipsing through the officers of NSW ministers because NSW ministers are required to make public their diaries, however imperfectly. The diaries however have only captured the visits of industry bodies and lobbyists with ministers, not with junior ministers, staffers, or bureaucrats. NSW also keeps a register of lobbyists, but again, there are important limitations on how well this is working.

NSW has a deplorable history in water governance. Before the predictable actors start sharpening their pencils, I refer readers to the highly disturbing findings of the Independent Report on Water Management and Compliance (the Matthews Report 2019) and to the four NSW Ombudsman’s reports into NSW water governance and compliance. It is truly your privilege to read the fourth one, because the Ombudsman made sure to table it in parliament. As the Ombudsman pointedly noted, the earlier three had been provided to the minister- none of them was published.

It’s kind of hard to disagree with the assessment of grazier Stuart LeLivre that “NSW couldn’t manage water in a dunny.” In due course, I will be coming back to all of these themes in detail, as I explore the networks that have produced possible conflicts of interest and undermined sound water governance and water policy in this country in detail.

Meanwhile, the NSW ICAC is now looking into how NSW regulates lobbying and access to politicians. In 2010, a similar investigation which recommended important changes to lobbying and transparency mechanism was quietly ignored. Only five of its 17 recommendations were adopted. The NSW ICAC is asking the public for input into how to regulate lobbying, access and influence in NSW — it wants public input into issues like: how to regulate revolving doors; whether NSW should have a “fair consultation process”; how to resource disadvantaged groups; how to regulate lobbying, and enforce it; and how to make lobbying transparent. The closing deadline for consultation responses is very soon — 25 May 2019. Here’s the link.

There is nothing wrong with making representations to government, and indeed, our democracy depends on exactly this. We don’t want to kill the whole tree, but we do want to control how it grows. As first cab off the rank, to the citizens of NSW, I say it’s your move. Move now, and move hard.

———————-

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. Triskele’s identity and bona fides are known to us. Triskele  is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.

You can follow Triskele on Twitter @Triskeltic .

Tandou Can Do: double standards in water purchases in the Murray-Darling Basin

Public support is vital so this website can continue to fund investigations and publish stories which speak truth to power. Please subscribe for the free newsletter, share stories on social media and, if you can afford it, tip in $5 a month.

The above investigation is published anonymously at the author’s request. Triskele’s identity and bona fides are known to us. Triskele is an academic and journal editor as well as independent researcher interested in politics, history, current affairs, books, languages, and “all things nerdy”.