Are the raft of housing stimulus schemes, low interest rates and relaxed lending rules for banks playing well for new home buyers or playing into the hands of property developers, existing homeowners and bankers? Harry Chemay reports.

A curious thing happened in the days leading up to the 2021 Budget. Data released by property analytics firm CoreLogic indicated that the value of Australia’s residential housing had surpassed $8 trillion. That’s an eight with 12 zeros after it.

Take the total value of Australia’s GDP. Add the market capitalisation of the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), and then include the sum total of Australia’s superannuation system. You’d still be about one trillion short of the value of Australian residential property.

Australia’s housing market doesn’t just exceed the productive economy, it simply dwarfs it. There seems neither the political will nor the desire to tackle this growing imbalance. Quite the opposite, it would appear.

According to CoreLogic, the median Australian house price rose to $655,557 during April. After a brief Covid-induced respite during 2020, the market has roared back, experiencing its highest monthly rate of capital growth in 32 years during March.

Property investors, having sat on the sidelines last year, are back in the game. Over the past six months, house sales are running 19% above their decade average, with the median selling time for houses at record lows.

The fading Australian Dream

Nowhere is the high cost of housing more acute than in the nation’s two largest cities.

Sydney’s median house price has risen 13.4% in just the past six months, now sitting at an eye-watering $1,147,352. Melbourne’s is up 9% over the most recent six-month period, to $869,676. Both cities are now among the least affordable housing markets in the world.

A 2018 study of long-term house price growth, featuring Australia and 10 other developed economies by UK-based economists Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, found Australia’s real house prices had by far the highest growth over the period 1900 to 2017. Their work showed Australia’s real house prices grew by almost three times the peer average during that period, and by 65% more than the next most expensive market (the UK). Interestingly, the divergence has widened noticeably during the past 20-odd years.

It’s a view echoed by the Committee for the Economic Development in Australia (CEDA), which in its comprehensive Housing Australia report noted that “those not fortunate enough to have purchased their first home by the mid-1990s have found it increasingly challenging to break into the home ownership market”. The report also highlighted a range of policy measures, including negative gearing and changes to capital gains tax, contributing to the problem.

Ballooning prices wouldn’t be such a concern were real incomes rising with the cost of housing. Research by the Grattan Institute, however, reveals that while real average full-time earnings have broadly doubled since 1970, real house prices have near quadrupled, making that first foot on the property ladder ever more tenuous, and the level of debt thereafter increasingly burdensome.

Budget measures to tackle unaffordability

This year’s Budget contained a number of policy measures targeting housing, none of which is likely to move the dial on affordability.

Many are mere extensions or amendments to demand-side housing affordability measures introduced in the 2017-18 Budget, such as an increase in the amount able to be withdrawn from voluntary salary contributions into superannuation, via the First Home Super Saver Scheme, from $30,000 to $50,000. Or the reduction in eligible age from 65 to 60 for those interested in selling the family home and contributing part of the proceeds into superannuation via a downsizer contribution.

Then there is the New Home Guarantee, a rebranding of the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme, which will allow up to 10,000 eligible participants each year to apply for a home loan with as little as a 5% deposit, via a facility that effectively provides a guarantee to the lending financial institution of up to 15% of the property’s value. Which bank wouldn’t jump at the chance to lend to an otherwise marginal borrower if the taxpayer is providing a sizable equity buffer in the event of default?

A more targeted version, called the Family Home Guarantee, will help up to 2,500 eligible single parents each year to buy a property with as little as a 2% deposit. When compared to the near 480,000 low and very low-income households in unaffordable rentals, this measure seems grossly inadequate.

And finally, there is an extension to and further amendment of the HomeBuilder scheme. It’s been an absolute boon for the residential construction industry, with the initial estimate of $688 million of taxpayer funding now expected to top $2.5 billion, as the government continues to divert a significant amount of taxpayer dollars to the sector.

HomeBuilder: a sneaky plan for the Coalition’s franking credits crew to collar the pension?

Banking on bricks and mortar

House prices do not rise in a vacuum. In addition to accommodative policy settings, the jet fuel of finance must be ever-present to sustain an upward trajectory.

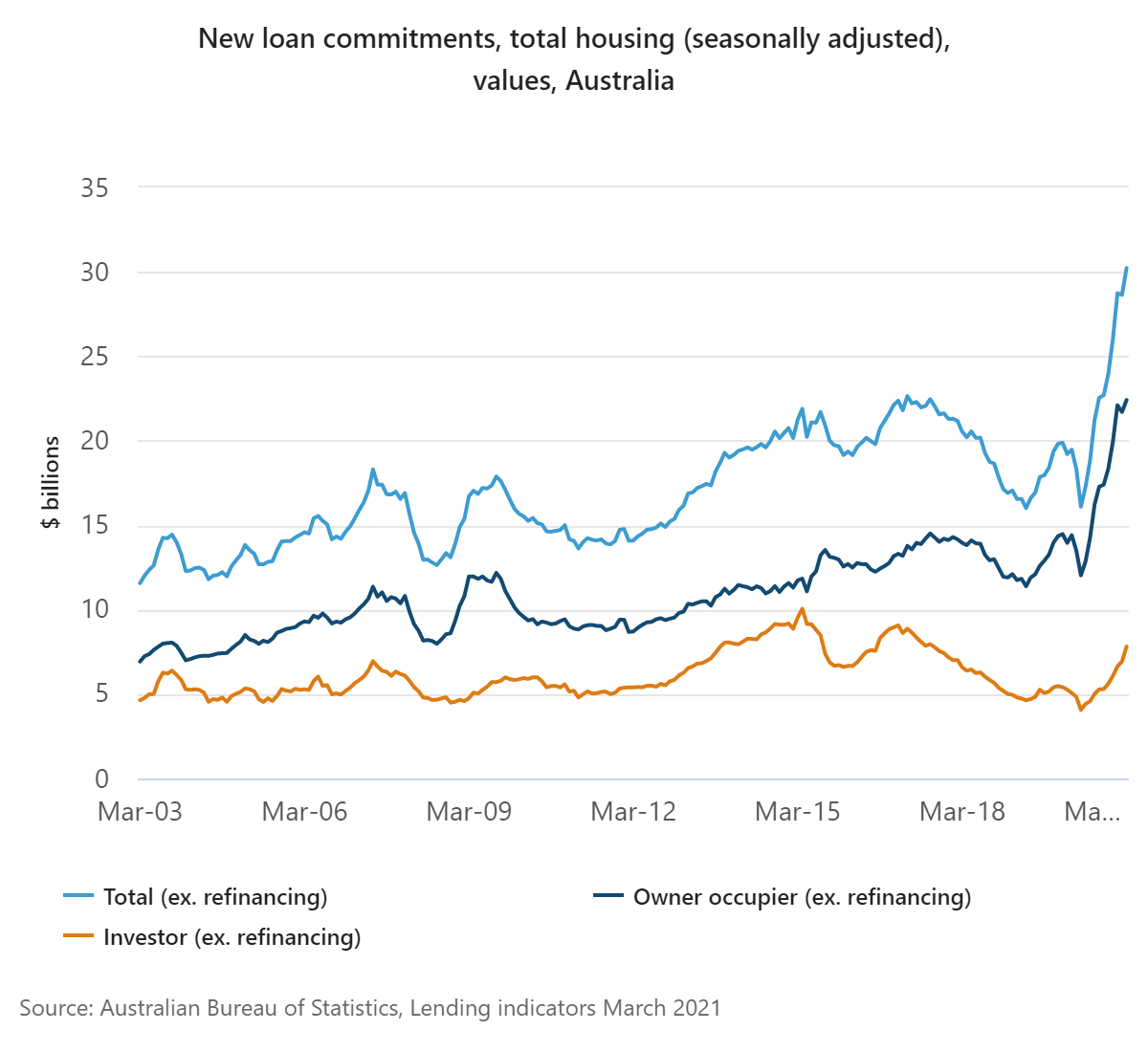

Despite a global pandemic that brought parts of the Australian economy to its knees, housing finance has instead boomed. While first home buyers and owner-occupiers had less competition from investors last year, the latest housing finance data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics suggests new loan growth is now at unprecedented levels.

Source: ABS – Lending Indicators (March 2021)

Remarkably, while new loan commitments to first home buyers increased by 61.4% in March 2021 compared to a year earlier, the corresponding figure for residential construction rose an eye-watering 123.6%, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

In short, that $30 billion of construction in the HomeBuilder pipeline is a boon for both the home building sector and the banks.

With demand for housing finance skyrocketing, it’s no surprise the banks are also in favour of the government’s attempt to wind back the Responsible Lending Obligations legislation, ignoring the recommendation from the Hayne Royal Commission that the RLO laws be both maintained and appropriately regulated to limit consumer harm.

Less onerous lending obligations, mortgage rates at historic lows and government programs stoking the flames of the property market would be a heady combination indeed come banker bonus time.

Feeding the property beast

According to the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, the rate at which renters become homeowners has been in steady decline, falling from 14% in the early 2000s to 10% more recently.

The decline, notes AHURI, is more pronounced for younger age groups and lower-income households.

It is, however, not in the government’s interest to upset the nation’s 5 million-plus home-owning households or the owners of the nation’s 2 million-odd residential investment properties, compared to the 120,000-some Australians who manage to scramble on to the property ladder each year.

However, the burden isn’t just borne by renters seeking an entry point into home ownership. The ramifications of larger, longer mortgages increasingly commenced later in life will ripple through the economy for decades, with AHURI finding the real mortgage debt of those aged 55 plus increased more than 600% between 1987 and 2015.

Approaching retirement with significant outstanding mortgage debt may become a feature, not a bug, of future retirement.

For now, however, the game of property snakes and ladders goes on regardless. There’s simply too much at stake by too many vested interests for it not to.

Harry Chemay has more than two decades of experience across both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. An active participant within the wealth and superannuation space, Harry is a regular contributor to investment websites in Australia and overseas, writing on investing and financial planning.